A wide strip of paper was unrolling slowly from the teletyper. A guillotine

edge cut across rhythmically, and the sheets were passed to a curved desk

where two men sat with shades to their eyes. One looked up, hand poised

over a page.

A wide strip of paper was unrolling slowly from the teletyper. A guillotine

edge cut across rhythmically, and the sheets were passed to a curved desk

where two men sat with shades to their eyes. One looked up, hand poised

over a page.

The story continues Nick Riordan's adventures from Time Was.

Reading note: The character Nick Riordan first appeared in Time Was, in New Worlds 12. The two stories were combined into a single volume, with a little new material, and issued as "The Star Seekers". In the text below and in "Time Was...", [text added to the combined stories] has been added in square brackets [ ] in italics. Minor changes and omissions eg saloon to sedan have not been indicated.

Given a near-Utopian world, will Man be content to rest upon his laurels, or will some enquiring minds still want to attain the impossible ?

Illustrated by CLOTHIER

The city of the New Men shone under the rose-tinted sun. High buildings pointed at the sky, where summer clouds drifted. Slender vehicles sped along the busy streets, and flitted into momentary view on the long bridges spanning from block to block. A murmuring pulsation of activity rose, coming more and more faintly to the higher and higher balconies rising tier upon tier to the sky.

Nick Riordan turned his back on the scene, went along the 20th level corridor, and stepped into the shaft of the anti-gravity lift. As he floated down he examined his companion closely. The young man, clad in sparkling plastic, was brown, - lean, and noble-featured. [He had been Nick's close friend since the first hour of their arrival.]

“All this means — absolute security,” Nick said.[“You should all feel content - safe - ”]

Timberley nodded, his eyes alive. “Absolute security,” he agreed. “Yet man’s every invention has arisen because men were not secure and satisfied ! Only because of want arose new techniques, or improvements to old.”

Their descent slowed, giving a sudden feeling of weight, and they alighted at the foot of the shaft. Nick led the way out into the sparkling street.

“You mean that absolute content causes stagnation, and that out of stagnation comes — death,” he said. “If growth and progress cease, decay must set in.”

“Exactly. [ We needed to prevent your Project 13 rocket from reaching us and introducing old customs. But that is not the only problem.]”

They entered one of the sleek vehicles which followed a route to the city centre. It started automatically, and illuminated tunnel-ways and rosy sky with streets below alternated as they flashed along the raised ways. Nick wondered exactly what his wife Niora thought of it all.

“But suppose the content and quiescence comes because the ultimate level of progress has been reached ?” he asked. “That might be different.”

“No.” The young man shook his head, staring moodily out from the autocar’s windows. “Mankind can never reach the ultimate point of progress. Every discovery suggests others; every invention opens new fields for exploration. It is a sequence without end.”

Nick understood the bitterness in the words and voice. Timberley was one of those who always looked further ahead, no matter how far he went, and always saw that the end to progress had not been reached.

“Progress is a stairway that tops infinity,” he had once said. Nick agreed. And Timberley had tried to step too far — and been halted with an unpleasant jerk . . .

“You think Wyndham will help ?” Nick asked.

Timberley’s gaze remained on the streets. “He may. I hope he will. His ideas are not stagnant. He does not regard stagnation as safety, but as the beginning of rot and disaster. He has always been progressive.”

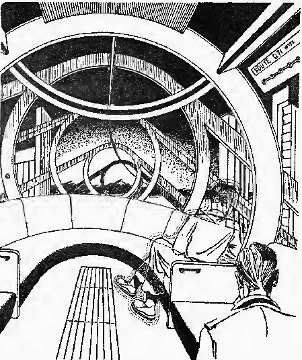

They emerged on a long, curving viaduct which spanned a break in the city. The autocar’s wheels hissed on the rails, and Nick gazed outwards from the buildings. Far in the distance beyond the town stretched the huge spaceport which was always a source of wonder to him. Huge vessels, tiny with distance, rose from it with apparent silence. They glinted in the sun, then were gone, speeding through the scattered clouds, which rolled turbulently like smoke in their wake. The buildings at the spaceport edge, huge as the ships themselves, looked like toy bricks dropped upon a creamy carpet, and the men who moved around them were minute dots.

“And all those ships go on closely scheduled journeys,” Timberley said

with feeling. “Not during my lifetime has an exploratory trip been made.

Authorities say we know all that we need to know — that exploration may

uncover something dangerous, upsetting our stable society ! Explorers

landing on new planets might bring back unknown diseases. The known

section of the universe contains all we need, they say. So searching for

newer worlds is not permitted.”

They sped into a tunnel and Nick wondered whether the man they were

travelling to see would help. If he did not, there appeared to be no way out.

The autocar stopped before a huge cream and green block which rose a full thirty stories against the heavens, and they alighted. The vehicle disappeared on its circuit, and side by side they went into the lift shaft, floating up, their speed increasing, until they came to the tenth floor. Round the comer of the corridor offices bore Wyndham’s name on every door. A young man sat behind a reception desk, but shook his head.

“Commander Wyndham isn’t seeing anyone to-day.”

“I’m a personal friend,” Timberley pressed. “This is important.”

The other looked harassed. “He — isn’t in.”

Nick saw Timberley grow tense. “Not in ! He’s always in at this hour !”

The clerk’s opposition collapsed. “He — hasn’t been here to-day, sir.”

Nick felt a tiny shock. This was the last thing he had expected, and

Timberley’s face was suddenly pale as he leaned over the desk.

“Not here to-day ?”

“No, sir. He hasn’t been seen for twenty-four hours . . .”

They were silent as a desk communicator rang. The clerk snapped the switch and repeated mechanically, “Sorry, sir, Commander Wyndham isn’t seeing anyone to-day.” Then they looked at each other, and Nick saw that something very near sudden panic had appeared in Timberley’s eyes.

“Twenty-four hours,” he breathed.

“Yes, sir. But please don’t repeat it. We hope he’ll turn up. Every effort

is being made to find him.”

They went out, leaving the anxious clerk repeating his statement into

the communicator.

“Not in,” Timberley repeated. “And they won’t find him. Of that I’m sure ! That was how it began with the others.”

The others, Nick thought. The significance of the words remained with

him long after he had parted from Timberley and taken his way, alone, to

his suite. There had been others, he remembered now. They had vanished.

Undramatically, silently, yet absolutely. A few had been ordinary people,

and scarcely made news. Others had been better known, but their disappearance had not aroused wide interest. Reviewing the details, Nick

thought that perhaps someone behind the scenes had arranged that there

was no stir in public interest . . . Wyndham, the city civil commander,

would make headlines, however . . . unless that same someone behind the

scenes hushed it up. Nick frowned. There had been quite a dozen disappearances in all, so far as he knew. Others, about which he did not know,

could have taken place.

Niora was sitting on the foam window-seat and her golden eyes greeted

him. Nick hesitated as he closed the door.

“Something’s happened,” he said abruptly.

Niora’s beautiful face wore an expression he could not define. She nodded.

“Marsh Wallace has been here.”

“Which means—?”

“That everything isn’t quite what it seems, Nick. He wonders why people have vanished. In a perfectly balanced community there should be no misfits who want to drop out. Then again, why can’t the missing people be found ? That’s what Marsh Wallace wants to know. He’s been looking long enough, and found exactly nothing.”

Nick felt amazed that these words echoed so nearly his own thoughts.

But the unease on Niora’s face worried him. “It’s a question many other

newsmen must have put to themselves,” he said easily. “Is that all ?”

“Not quite, Nick. He wanted you to go to see him.”

Nick’s interest quickened. Wallace was a busy man, and had soon won an important place in a busy concern — the Planogram Syndicate, which dealt with all the news of two hemispheres. Wallace would not want to see him unless it was something important . . .

“When ?” Nick asked.

“Soon as you can go round.”

That was Wallace, too, Nick thought. Get moving. Hunt your facts down. Don’t waste time. He wondered why Niora looked uneasy; why there was a thin vertical line between her pencilled brows and a shadow in her eyes.

“You’re — happy ?” he asked.

“Of course. Who wouldn’t be ? Everyone has everything they want or

need.”

She did not meet his eyes. Her words meant exactly nothing, Nick thought, as he went down and took an autocar speeding on an unending circuit which included Marsh Wallace’s office block. Niora was hiding something. And granting that to be so, two new questions arose. What was she hiding, and why ?

Marsh Wallace appeared to have been waiting. He dismissed an assistant and leaned back in his chair, his wide, brown face expressing welcome. A quiet hum from the adjoining offices, and the levels above and below, filtered in.

“Glad you’ve come, Riordan.” His voice was clipped, his eyes keen under bushy brows. “Didn’t expect you’d be out when I called.”

“I’d gone to look up Commander Wyndham.”

The keen eyes flashed a question.

“He was gone,” Nick said flatly. “Been missing twenty-four hours.”

Marsh Wallace’s expelled breath hissed in the sudden quiet of the room.

“Now he !” He walked jerkily round the desk. “You know he’s not the

only one ?”

“I’ve heard rumours ”

“They’re more than rumours: they’re fact !” Marsh Wallace made an

expressive gesture. He sat on the edge of the desk. “Listen. No news

reaches the public until it’s been through the Syndicate offices. We’re big.

So big even I, after working here a year, only have a hazy idea just how big.

News comes in through a myriad channels, and goes out through thousands

more. There are so many bosses no one knows who controls what — or if a

few know, they don’t talk . . . Three times I drew up copy and passed it on

to my next department, and three times that’s been the last I’ve seen or

heard of it ! Those facts never became news. And their removal was

arranged in such a way that no one knows at which stage the copy vanished.”

Nick considered carefully. “Someone in the Syndicate buildings is suppressing facts they want soft-pedalled.”

Marsh Wallace nodded, but not wholly in agreement. His tufty brows drew close.

“You over-simplify.” He gestured at the machine set on one end of his

desk. “My news, views and copy are recorded. They go by land-line to the

editing section. I worked here six months before I found where that section

was. It’s among ten thousand others, half a mile from here. The land-line

signals come off a teletyper as a script the staff can snip and handle.” He

paused, and from the look in his eyes Nick knew the crux was coming.

Wallace got off the desk and began pacing. “Yesterday something arose

which only happens once in a lifetime in an up-to-date office like this. A

complete power breakdown lasting half an hour. I took time off and went

round to the office where my copy goes. The teletyper there was still working.”

Nick experienced a shock. “Working !”

“Yes — while the sender mechanism, on my desk here, was out of action

because of the power failure !”

Wallace gestured at the complex machine and Nick realised how intent

he had been on every word, and frowned.

“The land-line has been cut and teletyper impulses fed in from else-

where ”

Wallace shook his head. “It hasn’t ! The cables are coded and have been

checked. The engineers can have no cause to lie. A second man, who

didn’t know the circuit had already been gone over, gave the same report.”

Nick expelled his breath. “And — why do you want to see me ?”

“Because you understand these things ! Check those cables ! I’ll wangle you a technician’s pass. Set about it as you like, but remember these two points. First, to help you, I shall send no copy from my machine for an hour, from eight this evening.” His eyes went to the wall clock. “That gives you time to collect your gear.”

He returned to his chair. Nick got up stiffly from the mushroom stool,

but stopped with his hand on the door.

“You said there were two points . . .”

Wallace nodded jerkily. “There are. The second may mean as much—

or as little ! — to you as it does to me. It’s this — a paragraph I wrote saying

progress was hindered by no one being permitted to make any further

exploration, development or invention, was among those never published.”

He paused, his eyes on Nick. “So was a paragraph on Barratt-Maxim . . .” [a name you'll have heard]

Outside, Nick’s head whirled. He felt he was required to remember too many things, each important, too quickly. The teletyper which worked with no signal; the land-line that was not tapped, yet acted as if it were; the disappearances; the curtailment of the inventive faculties of mankind. And, last but most shocking, the cryptic words about Barratt-Maxim, venerable, respected and universally admired civil leader of the city. Nick felt dazed, as if a complex puzzle had been thrown down before him, with no hint of the rules upon which it was to be reassembled into a comprehensible whole.

The clocks along the corridor stood at a few minutes to eight. Nick walked

slowly towards the door behind which the teletyper operated from Marsh

Wallace’s office snapped at high speed. His feeling of tension grew. He had

familiarised himself with the run of the cables to Wallace’s machine, and

had spent an hour examining them without result.

The machine in the office hesitated, was momentarily silent, then the rapid clicking recommenced. Nick’s eyes went to the nearest clock. The second hand had just passed the hour. His lips compressed and a feeling of unease drew taut his nerves. He pushed open the office door.

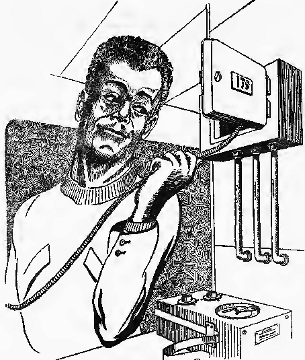

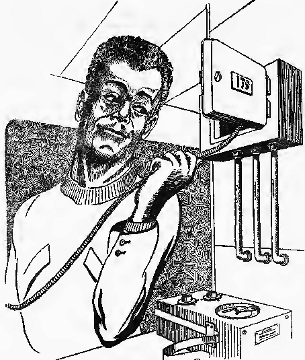

A wide strip of paper was unrolling slowly from the teletyper. A guillotine

edge cut across rhythmically, and the sheets were passed to a curved desk

where two men sat with shades to their eyes. One looked up, hand poised

over a page.

A wide strip of paper was unrolling slowly from the teletyper. A guillotine

edge cut across rhythmically, and the sheets were passed to a curved desk

where two men sat with shades to their eyes. One looked up, hand poised

over a page.

“Well ?’’

“Sorry— wrong room.”

Nick withdrew. The machine was operating; it only remained to find where the motivating signals arose. He opened his kit and took out a meter which would show the strength of the currents anywhere in the line.

They were strong in the annex adjoining the office, where the cable issued through a conduit. Strong, too, at the next junction point, and the next. Conscious that time was passing too quickly, Nick went to an observation junction near Wallace’s office, hoping to get the other side the point where the current was injected, and work back. The signals were strong there, too. He frowned, took two more readings, and saw that three-quarters of an hour had passed. No observation junction remained between the point of his last test and Wallace’s machine.

It was a long way round and when he reached Marsh Wallace’s office Wallace was talking into the machine. Nick’s eyes flew to the clock. The hand was just on the hour.

“So you didn’t stop ?” he asked quickly.

Wallace looked up. “I’ve just started ! An important item. I gave you an hour.”

Nick withdrew, puzzled. In the corridor, he reconsidered the blue-print of the land-line circuits, engraved on his memory. From the office to the first junction the line ran through a conduit built into the walls of the block. It would be a major engineering job to tap them. It was odd, he thought. Very odd. If the impulses had not been coming from Wallace’s machine all the time — from where ? It did not make sense.

Puzzled, he slowly left the corridor, settled to street level, and went from

the building. Outside, he stood in thought, momentarily letting the stream

of people flow round him.

The city was modern, bright and pleasant, he thought; the people happy,

with useful work and ample and interesting leisure. No one lacked anything.

Medicine had reached a high level. Diseases were few, and there was ample

opportunity for a full and happy life. Very different from Old Earth, he

thought, where there had been want, disease, failure and misery. Here was

plenty, health, success in whatever branch of work and play each individual

chose, and universal content. Sometimes he felt a little out of place, as if

too strongly rooted in the past. Perhaps he looked at things differently from

the people passing around him, he thought. Perhaps Wallace did, too.

He realised that it was growing late, and mounted a raised way to board an autocar for home. Still in thought, he stopped on the narrow platform. A man was just boarding a vehicle which had slid to a standstill. The man was elderly, with mobile features. His white beard, smooth as silk, made him conspicuous. Tall and slender, he stepped easily into the car, moving to one of the seats in its deserted interior. The door was closing, the vehicle Nick should take already hissing to a standstill on the other side of the platform. But Nick’s eyes were on the solitary passenger. Barratt-Maxim.

His feet carried him through the door just as the autocar started forward. He sat down, wondering whether his impulsive action would prove pointless.

Barratt-Maxim sat three seats ahead, facing the way they travelled. He had not looked round. Unmoving, his eyes were directed straight ahead, and Nick felt an inexplicable unease. The rows of double seats stood empty. An illuminated disc showed Nick he was on the Q71 route, one but little used, and which would carry him away from his suite. Lights twinkled through the windows, and the city sped past, below, around and above them.

“So was a paragraph on Barratt-Maxim,” Marsh Wallace had said.

Those words had keyed the impulse bringing Nick into the car, and he wondered if he had come on a fool’s errand. He began to calculate how long it would take him to get home, and wished he had not come.

They passed between huge buildings, through a tunnel, and over a long bridge. Below were boulevards where floodlights had snapped on, illuminating fountains sparkling in ruby, green, blue and yellow. The hues shone on the silken head of the man in front. Nick looked away from him, directing his gaze downwards. He never failed to marvel at the beauty of the city, and no smoke clouded the starlit sky.

They swished over a second bridge, and high buildings showed ahead,

penetrated by a tunnel through which they must pass. A shock ran through

Nick from head to toe, seeming to twist every cell in his body. His nerves

jumped, his muscles knotted, and he lurched forwards in his seat. Then the

tension eased . . . Breathing heavily, he sat upright, cramp still twisting

his limbs, and gaped... Barratt-Maxim was gone. No silken head showed

above the back of the seat. The Q71 route vehicle, just flashing from the

tunnel, was empty except for himself.

He got up, stumbling drunkenly along the autocar. Every seat was empty. No one slumped in the place the old man had occupied. Nick walked to the front of the vehicle, looked through the curved nose at the rail streaming above, and went back to the tail, where bridges and buildings receded rapidly. Nowhere in all the vehicle was there space for even a child to hide.

When the autocar stopped he alighted shakily, his head spinning, and watched it speed away. Barratt-Maxim had vanished during that fraction of a second when the strange feeling of shock to nerve, mind and flesh had come, he was sure.

Evening air stirred through the city and Nick felt it on his brow, cooling

the perspiration standing there. He slowly sought a platform serving the

route which would take him home. He had had enough, he thought. Plenty,

for one day !

For an hour Nick watched the flickering reflections of street lights upon

the ceiling, and searched for a meaning to what had happened. It was after

midnight when he knew that he must go out again. Niora awoke as he

finished dressing.

“You’re not going out, Nick ! What for ?”

“To ride the Q71 route !”

He left her frowning as if she thought him mad, and reached the platform where he had seen Barratt-Maxim. Few people were about. Minutes passed, then a vehicle sped from the opposite tunnel and halted. Nick slipped in. He had expected the seats to be empty, and they were. The autocar moved away, gaining speed, and he sat down, the feeling of tension strong upon him.

Arched tunnel-entrances sped up and shot behind; streets stretched far below. Tense on the edge of his seat, Nick strove to remember every feature of the route. The boulevards swept below, still floodlit, and the vehicle sped on to a bridge. High buildings loomed ahead, their windows dark, and Nick half-rose. He had not expected it so quickly: between those buildings, for a second, his eyes had strayed from Barratt-Maxim. During that second he had disappeared.

The autocar swept through with a murmuring echo. Nick relaxed, looking back. He had not known if something would happen.

He alighted at the first halt. The position of the high buildings was clear, now. He took a short trip on an adjacent route, then walked, choosing a footway level with the Q71 lines.

The buildings appeared to be deserted offices. That fact alone seemed odd, he thought. Such central premises should be in demand. The footway ran close under one row of windows. Near the end, in the shadow of girders flanking the Q71 track, he pushed in a pane of glass and entered, thankful that fire regulations made non-breakable windows illegal.

Office furniture stood under dust-sheets and he passed through unused offices. Beyond the last a short corridor led to the rooms adjacent to the wall beyond which the Q71 route lay, and his feeling of excitement mounted. This, he thought, was the testing point.

The end door gave access to a single long room. It was empty, but Nick’s first feeling of disappointment vanished quickly. The emptiness was odd. The room might once have been a store, situated where the sound of passing vehicles would not matter. But it had no air of disuse. The floor was polished; so were walls and ceiling. Nick examined them and knew why the feeling of strangeness had come. All were coated with a hard, brilliantly smooth, brown substance which could have been a high-frequency insulator. There were no windows, and the only break was at the door, through which reflected light made all the room glow.

Nick shivered. The room seemed to be a cavity. No other word could be applied. Oddly enough, whoever had adapted it for the unknown purpose which it fulfilled seemed to have always intended that it should be empty: its function lay in emptiness . . .

When Nick left he knew that he had never felt so puzzled, or so uneasy without being able to give a reason, before. Why should a room be prepared with such elaborate care ? For what purpose did someone desire that vehicles on the Q71 route should pass near that strange insulated cavity hidden in the building ? It was inexplicable.

Two days passed. Nick returned home to find Niora awaiting him. She

raised a finger to her lips and indicated the closed door of the inner room.

Nick thought her expression was troubled.

“Two men to see you, Nick,” she whispered. “They’re waiting. I don’t

wholly like the look of them.”

He closed the outer door. “Who ?”

“Never seen them before. The didn’t seem anxious to give names, but

wanted to wait.”

“I see.” Nick did not move to the inner room. He wondered what this

could mean.

“They’re an odd pair, Nick,” Niora said. “The one is a cripple — quite

dwarfed ”

“A cripple !” Nick almost forgot to speak quietly. “Surely not ! These

days, with manipulative and surgical treatment at the level it is !”

“He is,” Niora persisted. She moved towards the door. “The other is a

huge man — and I don’t like his manner.”

Nick passed in and closed the door. A huge man with jet hair, a large face and eyes that seemed to dart everywhere at once, rose heavily. In a second chair was the cripple, his feet not touching the carpet. Though tiny, Nick saw he was quite old, perhaps almost sixty. One shoulder was raised; his arms were thin as sticks and his hands tiny. Nick felt pity for him, followed by revulsion as he saw the face. It was mean; the eyes were black and pin-pointed, the lips thin with cruelty. Nick stopped, his back to the closed door.

“This is unexpected, gentlemen.”

The big man put out a hand. His grip was hard. It, too, could be cruel,

Nick decided, though apparently the big man intended it to be friendly.

“My name’s Wells,” he stated. “We want to talk private business. This

is Kern Millay — you’ll have heard of him.”

He indicated the dwarf, and Nick’s interest quickened. The name was

familiar, though momentarily he could not place it. Both were watching

him, evaluating him by some personal standard, and he did not like it.

“I have little time ” he said.

“You’ll have time when you hear what we’ve come for,” Wells stated. He sat down and the chair sank beneath his huge weight. “Kern Millay has money — bags of money — and he’s willing to spend it. That’s why we’ve come.”

Nick got himself a drink from the side cupboard, gaining time to think.

The two waved his offer away. “Why to me ?” he asked.

“Because you don’t take things for granted. We’ve heard you look into

things for yourself, and form your own judgments. And that you’re well

up in electronics.”

Nick nodded. “Maybe.” He did not point out that money had a limited value when no one lacked any necessity or reasonable pleasure. His eyes strayed to the dwarf, who was watching him with an expression only describable as avid, and he remembered why Kern Millay’s name was familiar. Millay had often spent fortunes on matters that interested him, and that had made news. The little man strove to speak.

“Sometimes he’s half-dumb,” Wells stated with frank brutality. “It’s part of his deformity. But his mind is one many could envy.”

A look passed between the two and Nick strove to decipher it and their relationship. Kern Millay seemed to hate Wells, yet respect his strength. Wells could be a paid bodyguard, or have a more equal status.

“Even now occasional throw-backs to a more primitive physical state

arise,” Wells said, examining Nick closely. “Sometimes all our surgical

and medical science can do nothing. Mr. Millay is such a case.”

Kern Millay squirmed on his chair. His lips quivered.

T-tell— him— ” he said.

Wells raised a big hand. “I’m coming to it.” He scowled, looked at the

carpet, then at Nick. “We can rely on your silence ?”

Nick thought perhaps Kern Millay was master, after all.

“Of course.”

“Good.” Wells breathed as if in relief, and Millay’s eyes settled on Nick

watchfully. Wells began to search for words with obvious care. “Mr.

Millay will pay, if you can do what he requires — will meet any figure within

reason most generously, I may say.” He gestured. “The matter is secret.

Mr. Millay would remain anonymous and I would be intermediary. We

should take a very poor view indeed of any — betrayal of trust on your part.”

The eyes met his, and Nick knew that the big man was no fool. A keen intellect lay behind those eyes. Nick shrugged, ignoring the threat.

“If I take on a job I abide by its terms.”

“Good.” Wells appeared satisfied. “You may recall a certain process, never perfected, which was denied further development by the Board. Mr. Millay wishes you to continue investigations in that subject. His payment will amply compensate for any danger of discovery. Secrecy will be to your own advantage, as the Board severely disciplines those who disregard its orders.”

So that was it, Nick thought. It all came back to what Timberley had

said: stagnation could be irksome.

“What process ?” he asked tensely.

[ “It will be one you will not personally have encountered.”

Nick felt his tension grow. “And it is...?”

“That to which its full and technical name is seldom given.”

The eyes watched him carefully. Nick kept his face expressionless. “Yes?”

Wells hesitated.]

“That of transmens-substitution.”

Nick felt as if the big man had struck him. He recalled the enormous advances in surgical and allied subjects made by the New Men. They could copy a person’s mental activity patterns — had done so, in the past. But this was more : was momentarily terrifying.

“The T.S. process,” he breathed.

“You have read of it ?” Wells did not wait for the nod. “Then you realise

the need for secrecy — and can gain some idea of the size of your reward !”

Nick felt Kern Millay’s eyes hungrily, avidly, upon him, and wondered

exactly what the set-up was. He nodded slowly, thinking of Barratt-Maxim,

though he did not know why.

“I’ll consider it.” He knew as he spoke that he would take the task on — not because of the money, but because it seemed to lead towards the clues he sought. “I’ll let you know to-morrow.”

Beyond that he refused to go. Wells helped Millay to his feet. When they were gone Nick mopped his face, and decided not to tell Niora of the offer: if she did not know, she could not worry. There might arise other reasons, too, why it was best she should not know . . .

Next morning he went through the teeming city to Timberley’s suite. Timberley worked three days each week, and the tiny busts of translucent plastic dotting his rooms showed how he spent much of his leisure.

“Commander Wyndham, now Barratt-Maxim gone,” he said flatly. “The news has just broken.”

Nick nodded. “Any details ?”

“None — just that he hasn’t been seen. The exact hour when he vanished

seems unknown.”

Not to me ! Nick thought. He wondered where they went. But that was a question an increasing number of people would give a lot to answer.

“I want you to tell me the background of the T.S. process,” he said

quietly.

The other started. His eyes clouded, filling with strong curiosity. “The

transmens-substitution process ! You’re not . . .?”

“I am,” Nic said. He sat down. “I’d rather get the background from

you than enquire elsewhere. People talk.”

“Very well.” Timberley went to the window, gazing down on the sunny

streets, not looking at Nick.

“It’s one of the few things I agree was rightly stopped,” he said. “T.S. could upset our whole society. Once again money would count — if one had sufficient. Where money failed, crime might try to accomplish. If there is one thing which could turn men again into beasts, it could be that. It developed from the simple copying of thought-patterns. Briefly, the brain is drained clear of all memory, then the memory and personality patterns of another person poured in. There you have it !”

Nick shivered. He had seen the copying of thought-patterns. Micro-probes scarcely a molecule in thickness penetrated through the skull and the minute fluctuations of the brain-waves drained away into the complex apparatus.

“With T.S. a person’s whole consciousness could be removed to another brain,” he murmured.

Timberley looked bleak. “That’s it ! And the dangers of the abuse of that power cannot be exaggerated. A rich man whose years were numbered might buy a young man’s consent. The rich man’s consciousness — his being — would be transferred to the other body, while the young man’s mind would find lodging in the old man’s body. Think what that could mean to a man of fabulous wealth who was near death ! A cripple might covet a sound body, a criminal find security as a helpless victim ”

“A cripple !” Nick breathed. Abruptly the look in Kern Millay’s eyes seemed to have new significance. It would be necessary to be careful, very careful indeed, he decided, and nodded. “As I thought. It opens up endless possibilities. It was refused permission ?”

“In strong terms. Some experiments were made, however. When the results became news, bedlam resulted — panic, from some, and frantic efforts, half-underground, by a few money-magnates who wanted new lives. I recall Millay the crank, as they called him, trying to get the process legalised. He said if a man could afford to buy a new body, then let him have it !”

Nick felt sickened. The idea of thus transplanting a person’s memories, thoughts and consciousness itself into another’s body repulsed him.

“There were some rumours that Millay has tried to get the subject reopened,” Timberley said.

Nick saw that he had learned all the other knew. It was as he had suspected.

There could be subjects in which man could quest too far, and this was one.

Only with the most careful control could such a technique be permissible.

It was, alas, a technique which came so near to fulfilling a dream that abuse

could not be eliminated. A rich man might obtain a new period of life:

might almost aspire to immortality. With such a prize, anything might

happen.

Nick began work as Wells directed, and his instructions were simple. He

was to study T.S. technique until he could build the necessary apparatus.

A simple order, but not so easy to execute, Nick thought. Secrecy hid the

methods employed, and only piece by piece, in the most laborious manner,

could an overall picture be formed. Nick decided that the apparatus which

he had once seen would form a good starting point. In a simpler community, it could have offered the perfect disguise, but the recording of

electroencephalograph patterns as identity checks had ended its unlawful

utilisation in that way.

In a week he had a good overall picture of the T.S. procedure; in two, an idea of apparatus which might achieve the desired result. He began to build, eager now, as he always was when developing something new in his chosen field of scientific investigation. Often he worked long hours, urged on partly by Wells, but largely by his own intense curiosity. There were snags to clear. Unanticipated difficulties arose. He worried at them until a solution was found. The hours he spent away from the workshops Kern Millay had lavishly provided grew daily more few. Often he was so tired when he arrived home that he scarcely answered Niora’s questions. As he realised success was in sight, and definitely attainable, his excitement mounted, preventing rest.

Timberley met him one evening on his way home — a meeting that might

have been contrived, Nick thought. Excitement made vivid his youthful

face.

“I’ve seen Wyndham !” he said.

Nick felt shaken. “Seen ! You mean found ? Where ?”

“I don’t mean found,” Timberley declared, and fell into step besides

him as they crossed a raised way. “It hasn’t made news, and won’t, because

there’s no proof.” He frowned. “It’s odd — strange. You know why I

went to see him originally ?”

Nick nodded. “They stopped your experiments into absolute zero temperatures.”

“They did. Snap, like that. No reason given. I fail to see how my experiments were illegitimate. The authorities denied permission for further work. I wanted Wyndham to get the decision reversed. When we went to see him he was gone. I’ve seen him since— -once. In my apparatus !”

Nick halted; a chill ran through him, coalesced on his spine, then dispersed

along his limbs. “In your apparatus ?” he echoed.

“In my sub-zero chamber! I went there to look up some data — at least

they can’t prevent me thinking of it. I opened the door — and there was

Wyndham standing in the chamber.”

Timberley halted, an odd pallor to his cheeks. He licked his lips.

“I could see straight through him,” he said.

Nick could think of no remark. A glance at his companion told him one

thing: Timberley was speaking the truth. He would never make a mistake

like that.

“You’ve no explanation,” he said at last.

“None.”

They gained the upper level and Timberley gripped his arm. “My work-rooms aren’t far. Will you look ?”

Timberley wanted him to look, Nick thought. Desperately wanted him to — his tone revealed that. Even though no explanation would be forthcoming, he still wanted Nick to look. Nick nodded.

“Let’s walk,” Timberley said.

They went along the raised way above the streets. A diffused murmur of

people and traffic drifted up, only occasionally lost as a railcar sped by at a higher level, its hissing wheels over-riding the background of muted sound from below. They went along a slender bridge and through a tunnelled

building. At the exit, they turned right and Timberley unlocked a door.

They passed through a small office and a workshop littered with equipment.

“The zero chamber is next,” Timberley said. “It was there I saw him. I simply opened the door ”

He turned locking levers and swung open a door of ponderous weight. The walls were feet thick; the chamber beyond perhaps six feet square. A shock ran through Nick; his throat grew dry.

Standing motionless in the chamber, still as a figure cast from glass, was a man of upright, severe yet kindly bearing. The light from behind them, passing through the door, shone on him, burnishing his outline to sparkling fire.

“Again . . .” Timberley breathed.

The figure turned with infinite slowness as if time did not exist for it, and

the kindly eyes regarded them across the empty floor. Nick raised a hand

to speak . . . Then there was nothing. The chamber was empty, and

Timberley staring at him.

“You saw it ?” he pressed.

His voice shook and Nick nodded.

“I saw — it.”

“He looked at us."

Nick did not answer. He knew that if he returned home his mind would

dwell upon this development, seeking an explanation.

“I’d like to stay here — to watch,” he said.

When he was alone he examined the chamber. Its walls were heavily insulated, reminding him of the cavity in the building beside the Q17 railtrack. He waited outside, but nothing reappeared. Two hours passed slowly, and he felt valuable time was being wasted. Lights shone on the buildings opposite, and moved in the streets below. At last he took a final look into the sub-zero chamber, closed its door, and went out. Wells was leaning against the corridor wall. He pushed himself upright, filling the passage.

“The boss don’t like divided interests,” he said.

Nick felt anger. He balanced on the balls of his feet, eyeing the large

man with distaste.

“What I do with my free time is my business.”

“You’re kiddin’.” Wells laughed. The sound echoed along the empty

passage. “When Millay pays a man everything he does is his business.

Remember that if you want to stay happy.”

Nick swore. “There are two opinions about that !”

Wells eyed him, his face ugly and his lips set close. “Remember there are things it’s best not to look into,” he said, and his gaze strayed momentarily past Nick. “There are others, too, who you might not like hurt . .

He scowled and Nick knew what he meant. Niora. She could be a weak link. He glared at Wells, not speaking. It would be best not to show his thoughts too much.

“Millay feels it’s about time we had some real demonstration,” Wells said. He moved to one side of the corridor. “He pays well — but expects value.”

“He shall have it,” Nick snapped.

He pushed past and went out. He did not look back to see if Wells

followed, or whether he went into the offices. I’m in it up to my neck now,

he thought. He knew there would be no going back: it was too late.

The silence of his rooms laid a cold hand upon his heart. He looked for a

message, knowing he would find none, then stood in the lounge, face frowning

immobility, and eyes cold as blue ice. The rooms were quiet, silent — lonely.

He wondered where Niora was. There were no signs of a struggle, but that

could mean nothing. The buzzer on the communicator in the outer room

sounded.

“Riordan there ?” a voice asked. It was Wells.

“Yes.” Nick’s voice was thin as plucked wire.

“Remember I said we wanted results ? Millay expects them to-morrow.

I advise you plan something.”

The instrument went dead. Nick swore. This could mean Wells had acted at once; the words could be a threat . . . Nick wondered how long Niora had been gone, and fancied her perfume still lingered. He sat down, pondering. She had been strange, somehow tense, the last few weeks. He remembered it, now, and cursed himself for not noticing before. He frowned and got a drink. If he followed that line, it meant Wells’s threat did not mean what he had first supposed it must . . .

At last he went to sleep, dog-tired, and knowing attempts to find Niora

that night would be useless. The city was big; ten thousand hiding places

could exist among its teeming millions. Worse, hasty action might endanger

Niora. His last thought before sleeping was of the teletyper which functioned

when it should not, and he wondered if Marsh Wallace lied, and had been

sending all the time.

Nick decided it wise to see Millay and Wells early. They sat in his basement workroom, sometimes watching him, and sometimes looking at the

equipment. Kern Millay followed every word with close attention. The

little face, slightly twisted by the same sport of nature, was a creamy white

under the ceiling radiance; the eyes glinted, and tiny droplets shone on the

forehead. Only once did he speak :

“Y-you believe it — completed, Riordan ?”

“I do,” Nick stated. “I have not needed to develop a new apparatus, but

only copy an old. The T.S. process is not greatly different from that used

in recording a person’s thoughts. The dissimilarity lies in withdrawing the

brain-waves and leaving the memory-banks vacant to receive the new

impulses which will be fed into them.” He felt chilled — a feeling which

always came when he remembered the power of the apparatus he had made.

There was something terrible in this ability to drain a body of memories

and personality.

“You can do it ?” Wells pressed, his face set.

Nick nodded. “As far as can be ascertained, yes. Everything is completed — but no actual test has been made, of course.”

Kern Millay rose with the aid of his stick and limped slowly to the

apparatus. Two complex chairs stood side by side. Above them, suspended

on counter-weighted arms, were enormous headpieces containing the micro-probes which penetrated bone and tissue to the brain itself. Behind, connected by heavy cables, was the mass of units which stored and transferred

the brain-waves. Nick had explained it all, and he wondered whether the

moment had now come when he should mention Niora. His part of the

bargain seemed to have been fulfilled.

Wells got up, his hands loosely in his pockets. He was twice Millay’s size and a foot taller. The expression on their faces halted Nick’s question. Wells was purposeful ; Millay was eager — yet afraid. Nick’s tensed muscles released themselves instantly and he sprang to the door, jerking at the handle.

It would not open. He remembered, too late, that Wells had come in last. He turned, ready to fight. Wells had withdrawn one hand and it held a paralyser.

“You’ve made a mistake, Riordan,” Wells murmured.

Nick saw the anticipation in Millay’s eyes, and felt horror. He knew, now, that he would not have come so unprepared, and alone, had he not been worrying about Niora. The thought came, and knowledge of his danger, and he sprang towards Wells, his arms reaching out to grasp the paralyser and tear it away . . .

A faint blue radiance played round the weapon and Nick felt his limbs crumble. Use went from arms and legs and he fell like a dummy. Consciousness did not go. That, perhaps, made it worse.

Wells put the weapon away. “Mr. Millay always expects — good value for money,” he said.

He dropped Nick into one of the complex chairs, expertly snapped the metal retaining clips over his arms and legs, and dragged back his head, securing it with a band across the temples. Triumph was added to the fear and anticipation on Kern Millay’s face. He mounted the second chair, squirming into place.

Nick felt sickened. Good value , he thought. The real meaning of those words was apparent. The body that had always been Nick Riordan was strong, and whole; Kern Millay’s was twisted, dwarfed and ineffectual . . .

He felt the enormous headpiece sinking on its levers to enclose his skull, and his thoughts became incoherent. Dimly he realised that Wells was manipulating the controls on the apparatus, working with an expert efficiency which proved he was no stranger to such equipment. As in a daze he realised that Kern Millay was motionless and half-hidden by the second headpiece.

No sensation came as the micro-probes sank through bone and tissue, but his thoughts no longer remained under his own control; instead, running with fantastic speed through strange sequences. Memories bubbled up like water in a vacuum, until he was nauseated. Slowly all feeling went. He was no longer aware of sitting in the chair, or of the cruel constriction of the clips Wells had dragged around his limbs. Memory seemed to dwindle, and sensation ... he did not even realise he could not remember, now, and his last coherent thought was one of gladness that Niora was missing . . . better thus, now . . .

Consciousness came back slowly, and with it a sensation of strangeness

which for a long time Nick could not place. His limbs seemed shrunken,

his blood to flow more slowly, and his strength to be changed to palsied

weakness. For a long time he sat with eyes closed, his brain curling, as he

recalled how he had come down into the basement, and how he had been

trapped.

His eyes flicked open. The workroom was empty, as was the chair besides him. He felt momentary surprise that he had been moved from one chair to the other. Then complete awareness returned. He had not been moved. He now occupied the chair where Millay had sat . . .

He swore, trembling. His feet did not touch the floor. One shoulder was permanently drawn up. His hands were white and thin, not the strong and capable hands he had owned.

He got up awkwardly, almost falling. Accidently or through a cruel jest Millay’s stick was against the wall near the door. It took him many minutes to reach it. He stood crookedly, breathing heavily, his face agonised and his thoughts gaining coherence. Kern Millay had had good value, he thought bitterly.

He hobbled to the basement lift-shaft, rose to street level, and went out. Already he felt exhausted, and realised why Millay and kept Wells in close attendance. At last he gained a seat on the boulevard and almost collapsed into it. As he rested he searched his pockets. One bulged, and he extracted a thick roll of currency: the exact amount Millay had promised. When he had counted it Nick laughed without mirth. The commission had had terms of which he had not been aware ! [The other pocket contained Henry Riordan's box, placed there, he supposed, with an honesty that mocked him. His fingers trembled momentarily on the seal, then he returned it unopened to his pocket.]

[He would go to Timberley, he thought. There at least, might be found help.]

At last he went on, painfully boarded an autocar, and alighted near

Timberley’s rooms. Exhausted, he leaned against the corridor wall, a finger

on the push. Finally the door opened, and Timberley’s brows rose.

“Mr. Millay !”

Nick forced himself upright, and staggered through the door. “I’m —

Nick Riordan,” he grated.

Disbelief, amazement, and comprehension passed through Timberley’s

eyes. He closed the door.

“The T.S. process ?”

Nick nodded, sinking into a chair, his breathing uneven. “T-tricked me,” he said. Words came with difficulty, but he found speech not impossible, and was glad. Perhaps Millay’s impediment had been partly of the mind . . . “Millay — is — me,” he said. “Must find him — make him change back.”

He read the emotion on Timberley’s face. How could they find a man in all the great city, when that man had every reason for hiding ? Timberley looked grave.

“Thought I saw you half an hour ago. That would be. . . ”

“Kern Millay,” Nick said thinly.

Timberley frowned. “Yes. I wondered why you didn’t reply.”

Nick expelled his breath. “Where was he ?” He leaned forwards, feeling

everything depended on the answer. [Millay must be caught.]

“Boarding a vehicle on the Q71 route.”

A sensation of hopelessness swept over Nick, almost overwhelming.

Barratt-Maxim had ridden the Q71 route, passing by that strange cavity of

unknown purpose. Millay would not go that way from mere chance.

“He might have ridden up anywhere along the east side of the city,” Timberley said pensively. “Or gone on the looped circuit south.”

“I think — neither !” Nick wondered just how far Millay’s planning had extended. He considered. The shock of knowing that Millay was gone — gone as completely as the others — shook him. To plan an effective countermove seemed impossible. He sat unmoving, his chin on his chest, conscious that Timberley was standing helpless by the window. Then he looked up.

“Get me Marsh Wallace !”

“He’ll be busy ”

“Get him. Tell him enough. He’ll come.”

Alone, Nick tried to integrate the isolated pieces of knowledge which must

surely form one whole. It was difficult. So many sections of the puzzle

still remained unknown.

Marsh Wallace leaned back in his chair and regarded Nick under heavy brows. His eyes held pity. “If you never find Millay you’re finished. And he’ll not let himself be found ! He’s been planning this a long time.”

Nick licked dry lips. “How do you know ?”

“Rumours circulating through Planogram say he’s sold out all his stock

and property. Big people are news, so we watch them. Millay was big.

He was ready to clear out.”

“And has gone,” Timberley added thinly.

Nick felt his dismay sharpen. He had hoped that by some miracle Marsh

Wallace could formulate a plan. Wallace was one of the few men he could

rely on.

“I feel we’ve missed up on something we should realise,” Wallace mused, “As Timberley said, the trouble seemed to begin because mankind’s questing after further knowledge had been forcibly ended. If that’s so, we shan’t find a solution in the mechanisations of mere individuals, even if as powerful as Millay.”

Man’s questing ended — by order, Nick thought. If that happened, what would man do ? Go elsewhere.

He took up his stick. “I’ve an idea. It may come to nothing.” He rose with difficulty, supporting himself crookedly, and paused at the door. “If Niora is found — tell her about me.”

Wallace halted him. “I’m in this too, Nick! You’ll need help.” His

gaze went over the deformed, weakly body.

Nick shook his head. “No one else is in on this. I wouldn’t ask them.”

He went alone from the building, and painfully through the city. It needed an hour for him to reach the point where the Q71 route passed by the cavity, and his exhaustion was extreme. Unshakably determined, he went slowly through the offices, still empty, and into the insulated chamber. There, he closed the door and sat down to wait and think.

Apparently Kern Millay had cashed in on something bigger than himself, taking the chance afforded. The others who had ridden the Q71 route— and vanished — were men of very different character to Millay. Wyndham, the civic commander, was kindly, generous and honest; Barratt-Maxim was justly a respected leader. Millay did not fit with them, Nick decided.

He listened, but no wheels whined on the Q71 route rail. He would not need to wait long, he decided. The route was not busy, but its vehicles kept their regular schedule, even if empty.

He wished he could have copies of the material coming from Marsh Wallace’s teletyper during the intervals when the signals apparently did not originate from Wallace’s machine. They might repay study. A secret coded message in the public press would never be suspected. Millions of words poured hourly from the Planogram Syndicate buildings, and only those who knew where to look would look in the correct place.

Wheels swished outside, and Nick tensed, nerves tight as strained wire. The swish passed . . . only a vehicle on the level above.

He expelled his inheld breath. What Timberley had said, repeating his

own words, was true. Man’s questing could never be ended. Men would

refuse to be contained. Mankind must always expand. The thought was

exciting; gripped by it, he scarcely heard the first sound of wheels on the

Q71 route. Then the noise swept near and he knew the moment had come.

Simultaneously a ringing began, coming from nowhere. Beginning very low

in the register, it mounted up and up to a humming like a deep gong; became

a continuously ringing bell, a shriek, a whine, and was gone above audibility.

Came the sound of the autovehicle sweeping through the tunnel. Lights

jumped from nowhere and curled and bobbed in the chamber; a man stood

besides him, miraculously come through the wall from the Q71 track, then

chamber and man vanished. Nick felt he was falling headlong through space.

Consciousness went; the sound continued in a high-pitched ping , then that,

too, ended. He seemed to be falling into real darkness, and staggered to

his knees, clutching at his stick.

Turf was beneath his feet, a gentle wind in his face, and stars above.

He turned slowly, striving to orient himself, and failed. Lights twinkled a

long way off, but he did not recognise them. He looked at the heavens again,

and froze. The constellations were unfamiliar. Many times he had looked

at the night sky, enjoying the stillness, and comparing the vista of stars

with the view seen from Old Earth. The hemisphere above was neither.

Unfamiliar stars stood in unfamiliar groupings. Two tiny moons were

chasing towards the horizon, and the air was subtly different. The gravity,

too, was reduced, and made movement easier. But the galaxies above were

unrecognisable — unknown to him, or, if known, now seen from a totally

unfamiliar viewpoint.

He went slowly towards the lights. The buildings from which they shone were few, and quite different from any other buildings he had previously seen. One was topped by a lattice tower, where a complex array of radiating antennae pointed at the heavens, pivoted about both vertical and horizontal axes so that the planetary rotation could be cancelled and power always be directed at the same point in space. A second building resembled a giant inverted staple, and others were obviously power-houses. He limped nearer, eyes and ears alert, and passed between two buildings. Ahead, the narrow alleyway opened into a wider road. A faint humming came from it and drummed between the high, sheer walls above his head. He slowly approached the alley end, looked out into the lit street beyond, and found himself face to face with an elderly man of upright bearing. The features were kindly, but alive with surprise.

“Kern Millay !” the man breathed.

Nick felt dismay, and the shock of recognition. “Wyndham !” — the

man who, in shadowy, unreal outline, had stood in the activity chamber of

Timberley’s sub-zero apparatus.

The kindly face grew bleak. A hand surprisingly strong settled on Nick’s

arm, preventing his retreat. Nick struggled and almost fell, but knew he

could not escape. As Nick Riordan — yes; but not as Kern Millay, whose

body was softened from inactivity and handicapped physically.

“We’d heard rumours that you were interested, Millay.” No friendliness

eased the tone. “Our plan is too big for us to permit that mere individuals

jeopardise it.”

Nick writhed with the pain of the other’s grip. “I’m — not — Millay !”

he stated, panting.

Wyndham frowned. His gaze passed over Nick with contempt. He

shrugged.

“A likely story.”

Nick protested, was silent, then asked: “Where are we ?”

Wyndham laughed shortly. “Why pretend you don’t know, Millay ? It

won’t pass.”

The street was deserted. They skirted the high building whence came the humming, and approached offices near the living quarters. Nick tried to drag himself free, but failed.

“You’ll find a very different set of ruling principles apply here, Millay,” Wyndham declared. He rapped sharply on a door. “Money means nothing; nor does personal prestige, unless backed up by ability. More: the old standards of non-progress mean — nothing.”

The door opened. A man Nick did not recognise sat at the end of a desk.

Beyond him, in a swivel chair, leaned a second man who drew Nick’s eyes

and he remembered the time he had slipped impulsively into the Q71 route

coach. Barratt-Maxim examined Nick sternly.

“He was near the east side,” Wyndham stated. “He’s an individual unlikely to have an aim other than personal profit.”

The man at the end of the desk leaned forwards, consulting notes. “A disturbance in the A2 cavity field was reported,” he said. “The presence of an unanticipated object in the cavity could be responsible. There was a high momentary overload.” His gaze flickered to Nick. “Where did you arrive ?”

“Just beyond the city - ”

The man nodded. “It could happen. Your presence caused just enough

displacement of the field to throw us that much out.”

“But I’m not Millay,” Nick objected in the silence that followed. “We

were — exchanged . ”

Three pairs of eyes examined him critically. “Could be a lie,” Wyndham

said.

Barratt-Maxim nodded. “Have we the means of checking ?”

The other shook his head. “Nothing short of the brain-wave pattern check would prove or disprove his words. We haven’t the means to do that test, here — or the records of Millay’s patterns. They’ll be back in the civic archives.”

They fell silent. Nick saw how it was. These men had heard of the T.S. process; were, indeed, ready to believe him if they had proof. But without proof they would not believe — dared not, because Kern Millay himself would have personal aims which did not tie up with their own. They were wholly just, but could not take chances.

“Put him with the other,” Barratt-Maxim ordered abruptly.

Two men conducted him from the office and to the next building, apparently serving as a prison. Lights showed in a few windows, and Nick supposed it to be unused. He was pushed into a room and the door closed. A lock clicked.

“This is unexpected — Millay ,” a voice declared.

Nick turned awkwardly and gazed up into the rugged, browned face which had been his. The eyes that were his regarded him with contempt. Nick’s blood ran hot; a red mist of fury came and his lips twitched.

“I’ll — get — you,” he breathed.

Kern Millay did not move from near the barred window. “Don’t try anything — or you’ll get a beating.”

Nick met the eyes, and saw that they had an expression he had never had, and which the soft diffused lighting could not hide.

“You’d— kill me ?” he said.

Millay nodded. “I am considering it. As a precaution.”

Nick bit his lips. Millay intended the exchange to be for always. That

provided ample reason why he should fulfil his threat.

“Then why not — in the basement ?” Nick said unevenly.

“Who can say ? Perhaps because some of the joke would have lost its

savour.”

Millay shrugged, and turned back to the window. The action showed his

confidence, and Nick knew it justified.

“You’re captive too,” he pointed out at last.

Millay did not look round. “Only temporarily. My coming caused a disturbance in the field, which was noticed, and I was caught. But they’re checking my records. Nick Riordan was trustworthy and progressive.” He laughed briefly. “I expect to be freed at any moment. They even think I will be useful here. My imprisonment is merely token.”

“They’ll find out you know nothing of the subjects I covered !” Nick

grated.

“Unlikely.” Millay regarded him momentarily. “My plans are too well

arranged.”

They were silent and Nick felt the hopelessness of his position. Kern

Millay had planned every action and considered every development. Nick

himself was unprepared.

“You didn’t ride on the Q71 route by chance,” he said.

“Obviously not. I do not operate according to rules of chance, but by pre-arranged plan. I pay many men to watch many things. One saw discrepancies in certain Planogram Syndicate items. From there to discovering what those discrepancies meant was easy. I pay men whose job it is to find out such things. So I came here, where there will be no brain-wave records to prove your claim . . .”

The lock clicked and the door opened. A man beckoned to Millay.

“We’re satisfied, Riordan. Commander Wyndham would like to ask you

a few more questions — but nothing important.”

“Good.” Millay’s eyes were triumphant. At the door he looked back.

“I understand there have been three displacements of the field . . .”

They went out; the door closed and the lock clicked. Nick stared at it,

Millay’s final words echoing in his mind. Three. That meant three people

had come. Millay, himself, and ? He did not know. He wondered whether it could be Niora, and hoped it was not. He supposed that whoever purposefully rode the Q71 route would sit first in the vehicle. Niora had

often liked to sit at the front. But that could mean nothing, and he could

think of no reason why she should traverse the route at all.

He looked from the window. Too small to permit escape, it gave a limited view of lit windows opposite. He gazed out for a long time, until the pain in his legs forced him to sit down. The couch was a fixture and the room bare. He lay full length, closing his eyes to think, but no plan formulated itself. At last, after a long time, his fatigue asserted itself and he slept.

Nick awoke knowing something had disturbed him, and saw that the door was open so that a thin streak of light penetrated from the corridor. He rose slowly, wondering if this meant danger, and edged along near the wall to peer through the crack.

The corridor seemed empty. He opened the door with infinite care and looked out. No one was in sight, and he listened. This chance of escape seemed too lucky, he thought. It could mean danger, or be a plan formulated by Millay to secure his disposal . . .

No sound came. He edged through and moved slowly along against the wall until he reached a corner, beyond which was a second door. His scalp prickled as he went through. The next room was empty. A window was open and he waited by it a long time, listening. If Millay had planned this, perhaps he was waiting until the fugitive came through the window . . .

Ten minutes passed in complete silence. Abruptly Nick swung himself awkwardly over the sill and dropped to the ground in shadows. No shout came, and no weapon burned through the gloom. He went quickly along the wall, round the building, and into a narrow alley. There, he leaned against the building, to rest and listen. His unease did not pass, and at last he went down the alley and round several corners, often stopping to listen and look back. No steps came in pursuit.

His idle flight must become purposive, he decided. A low humming sounded in the distance, and he followed it until a high building blacked out the stars, then went in shadows to the back, seeking a way in. Ahead, the antennae array stood, a glow surrounding it showing that it radiated power to some point in the heavens. Nick wondered what incalculable distance lay between him and the shining city where he had worked.

The building was not guarded; locked doors seemed superfluous. Nor was any door inside secured against his passage, and he crept from corridor to corridor and room to room, always ready to hide, and often pausing to listen. The night was quiet and he saw no one. As he moved he examined the apparatus around him; his retentive memory noted the details and he strove to deduce what purpose the many units had. The picture was incomplete, but he realised that here were new developments not seen back in the shining city. Not seen there, he thought, because they had been suppressed ! But inventive man would not be suppressed, and had taken himself elsewhere to continue his endless search for yet further knowledge.

Low voices came from behind a door. He opened it so slowly no watcher would have seen movement, and listened. He might lack strength, now, he thought bitterly, but he still had stealth and wit.

One voice sounded oddly like his own, and Kern Millay stood with his back towards Nick and near a panel of meters and dials. Wells sat on a mushroom stool, his heavy face in profile against the reflected light.

“It’ll be easy with the best men gone,” he said.

Millay grunted in assent. “We’ll not be over-confident. That could be dangerous. You believe it will work ?”

“So far as I can decide — yes. There must always be an element of doubt until a thing is actually tried. Practical tests back up theory. Apparently when one object equals another absolutely the two no longer remain different. One is the other. They co-exist. That is how the transmit apparatus works. Each cavity exists simultaneously in two widely spaced localities. Each is the same cavity. So what is in one must obviously be in the other. Hence our apparent instantaneous transit across millennia of light-years of space. Actually, we scarcely move. Short-range projection places the individual into the cavity. The cavity exists both here and there. With a further short-range projection out of the cavity here, the apparent transit is completed.”

Millay waved a hand around. “That’s how all this apparatus was transported ?”

“Undoubtedly,” Wells said, and Nick felt increased respect for the big man’s intellect. “They may have mined useful ores since. But undoubtedly the early stages of the scheme consisted in transporting here necessities for setting up and developing this terminal of the transit apparatus. The personnel is following. As a foolproof method of informing those in the know their method of using the public press was nearly foolproof. I have located the interferer apparatus — it’s in the next chamber. It induces teletyper signals directly into the cables in the Planogram Syndicate building. It could be used during quiet periods, or even over-ride the local impulses.”

He had expected something like that, Nick thought. He was glad to clear away the suspicion that Marsh Wallace was playing his own game, and had lied. Nick wondered what he should do. New and amazing developments had obviously been made in many branches of technology, and Barratt-Maxim, Commander Wyndham, and all those disappeared leaders whom he had felt most honest, wise and reliable, were willing parties to the trick.

“You’re sure the transit can arise both ways ?” Millay asked, unease in

his voice.

Wells nodded heavily, almost with contempt. “I deduce it must ! There

is no real movement. The cavity exists both here and there — is co-existent.

Through it, we can return as readily as we came. That the procedure works

in one direction proves it can work in both.”

He was silent, and Nick saw why Wells had so long held his position as personal bodyguard to Kern Millay. His knowledge was immense — would have indeed seemed more suitable in a thin, wizened scientist. Wells’s brains matched his brawn. Neither must be underestimated.

Wells swung himself off the stool. “Plans to enter the building by the

Q71 route are completed ?” he asked.

“Yes. It cost a great deal. The heavy machinery is also ready, stored

only a few blocks away.”

Nick wondered what was planned. Something for the personal benefit of

the pair, he supposed. Millay did not spend money on projects to benefit

others, insisting always on value for self. Value for self, Nick thought, and

a hot rage came and went abruptly. Millay did not care how others fared in

his deals . . .

They were approaching the door and Nick withdrew, limped down a

side-corridor, and slipped into a room near its end. He listened for them to

pass, but heard nothing. Abruptly, from nowhere, a hand fell on his shoulder.

“Looking for trouble ?” a cool voice asked.

Nick spun on his best leg. Dark eyes under bushy brows looked at him quizzically. A smile played over Wallace’s face.

“It comes often enough, without looking — Nick,” he said.

Nick felt relief. “You — opened the door ?” he asked.

“No.” Wallace apparently did not understand. “I’m simply searching for copy. Personalities are news. News is my business.”

His voice was grim and Nick wondered how much Wallace knew or guessed.

There would be copy here — but such as Wallace could never use ! Nick

felt his elation passing.

“Kern Millay and Wells have known what’s happening for a long time, and planned to profit from it,” he said slowly. “What the real situation is — as planned by Wyndham and the others — I don’t know. It must be something big for men of their calibre.”

Wallace listened at the door. “I can help you to understand at least a little,” he said. “Deduction again. Whatever it is, it’s bringing all the best men out. Millay may plan to slip back, take advantage of their absence, and prevent their return.”

Nick experienced a shock. This tied up with what he had been thinking. “Take advantage . . .?” he repeated.

“To gain personal power.” Wallace gestured. “He’s smarted under his physical handicap until it’s twisted him. He aims to get even with society, and with all those who feared him, because of his power, yet pitied him, for his deformity. He smarted under contempt, hating it. He planned the whole thing simultaneously on several levels — including the T.S.”

Nick looked down at his thin limbs, crooked-jointed, and his body, small as a child’s. Yes, he thought, Kern Millay’s mind would work that way. He had hated everyone who was whole of body with a burning, overwhelming hate. It fitted.

“The twelve leaders of the Civic Council disappeared before I came,” Marsh Wallace murmured.

Nick started. The quiet words meant the climax of the plan envisaged by Barratt-Maxim and the others was near. With it would come the time for Millay to act !

“I passed a report on for wholesale distribution,” Wallace murmured. “It should have reached the public before I came away, but did not.”

Nick thought of the teletyper controlled across all the vastness of space so that its leaders could slip silently from the shining city.

Doors were opening and closing and footfalls echoed suddenly down the corridors. Nick abruptly felt that there was strong danger — they had no knowledge of the hour when the operatives would return to the building, or whether warning systems existed. He saw that Wallace was uneasy too; his face was lined, his eyes mere slits as he listened.

“We’re not safe here,” he whispered.

Doors round the chamber opened simultaneously. Men stood in each, paralysers in their hands, their faces stern. Nick wished he could fight or run. He hoped Wallace would leave him, not jeopardising his own safety by trying to help. An officer came warily across the floor.

“Don’t move. Orders are to take you both, preferably alive.”

The tension went out of Marsh Wallace’s figure. “It’s no use,” he said.

Nick knew he had realised that from the beginning. They were trapped, outnumbered, and defenceless.

“Better to be taken — alive,” Wallace added.

The men marched them away, others following closely behind, weapons

ready.

“Apparently they’ve orders to take no chances,” Wallace breathed.

“There will be no escape this time, but guards, warned to extra vigilance ...”

Inside the council room Barratt-Maxim was flanked by men of severe

countenance. Every eye was closely upon them as they entered, and Nick

instantly realised that here was every leader from the whole of the shining

city — men renowned for their logic, fair judgment, and wisdom. Some he

recognised as familiar to every newscast viewer. Marsh Wallace nudged him,

his brows high.

“What this lot decides — that will be done!” he whispered.

A lean man with eyes of blue steel silenced him with a look; a whisper

passed round, and Wyndham leaned back in his chair.

“We cannot permit individuals to meddle with our plans,” he stated.

“The latter are too important to ourselves and to all mankind. Your presence

alone is annoying as you are not upon our list. We cannot tolerate interference.”

He dropped silent, brows bent heavily upon them. Nick wondered what it was these important men planned. Marsh Wallace expelled a deep breath and indicated Nick.

“He is not Kern Millay !” he stated. “You’ve heard of the T.S.

procedure ?”

One of the men nodded. “It was rightly outlawed.”

“But rumours suggest that Kern Millay spent a great sum on privately

developing it,” a second added.

“He has— here is the result !” Wallace pointed at Nick, his eyes alight.

“The procedure was used — Millay is free, as this man , Nick Riordan, who

himself redeveloped the T.S. technique !”

Silence came, broken for the first time by Barratt-Maxim. “Then he has earned the death penalty by using the process.”

Nick felt chilled. “I deny your right to set limits to the fields I explore !” he said thinly. “I intended no unlawful purpose — would not have permitted it to be so used.”

The circle conferred. Nick moved uneasily. “Millay and Wells plan to

make your Q71 terminal useless,” he said at last.

The eyes returned to him and Wyndham leaned forwards. “How ?”

“That I don’t know ! They plan to go back and move in machinery which

will somehow render the chamber useless, then take the opportunity afforded

by your absence.”

The whispering recommenced and Nick tried to catch its significance across the ten paces of floor.

“We accept your explanation,” Barratt-Maxim stated at last. “You should know several things. We are rebels, believing no limit should be set to man’s knowledge. It is not the knowledge itself that comes into error, but the way that knowledge is used. Almost every process can further killing, war, or crime, if perverted. To deny power to mankind is weakness; instead, men must be taught to use that power wisely.” He leaned forward, a flush suffusing his face. “We say there should be no end to man’s questing for knowledge ! We say a target at infinity is not one too distant for men ! Therefore we have begun again — here ! Those who stay behind in our shining city will follow their old ways, and travel to their known worlds. We seek new and unknown worlds. We set no limits. The universe is illimitable, and so is mankind. We do not wish to stagnate, fearing to search beyond known limits.” His voice rang like a gong. “We see no end to man’s invention, or to his expansion ! We are adventurous, because sometimes to adventure is to win. We are pioneers, and name ourselves the best of men and truly brave . . .!”

Nick felt the blood flow fast in his veins. These noble men were building for a new humanity never to be confined within prescribed limits of safety !

“One of us invented the instantaneous-transportaion technique,” Barratt-Maxim continued. “It was suppressed. The lawmakers thought it would give the adventurous power to go anywhere within the cosmos. It will. So they suppressed it. But we have used it — and shall use it more, until no world remains unexplored and no corner of space unvisited by man. It has brought us here, and will take us to new planets under strange suns. Here is no place for the timorous or the weakling. We wish ill to none; have planned so as to harm none ”

“But those back home will be harmed by Millay and Wells !” Nick interjected. “They intend to make use of your disappearance !”

Wyndham nodded. “It is true,” he agreed.

A shudder quivered through the ground, shook the room, and grumbled

away in a low undercurrent of heavy pulsations. Nick started as a communicator on the desk buzzed.

Commander Wyndham leaned towards it.

“Yes. Committee here.”

“Something odd has happened, sir !” Excitement trembled in the relayed voice. “We cannot maintain the hyperspatial cavity [by the Q71 track] !”

Barratt-Maxim paled. “Not maintain the cavity ?”

“No, sir ! The energy drain has leapt to an enormous level, yet the cavity has failed! Commander Taylor, scheduled to arrive through it several minutes ago, has not appeared.”