Illustrated by QUINN

Alexis Cutler lifted the phone, closing his ears to the click of teletypers in the adjoining office.

“ Alexis Cutler here,” a voice said.

The clipped briskness was his, the intonation, and Alexis eyed the instrument as if it were a serpent. This was the third time in three days.

He depressed a button that would put the conversation on tape, and a second to warn whoever was on duty line-tracing. The routine was learnt, as was the single monosyllable that conveyed nothing:

“Yes?”

Seconds passed, then a click told the distant receiver had been replaced. He swore silently and flipped the switch of the desk communicator.

“ That the basement ?”

A short delay, then: “ Yes, Mr. Cutler.”

“ Get any idea where that call was from ?”

“ No, sir. He rang off too soon — ”

“ Maybe recognised my voice. You’ll let me know if anything develops.”

Alexis switched off and scowled at his blotter. Young Clive, down in the basement amid the switchboards of the great building, hadn’t had a chance. Nobody could trace a call in seconds.

The blotter was covered with doodles a psychoanalyst would probably have liked to see. Alexis tore the top sheet off, screwed it fiercely, and flipped it into his disposal chute. The hum of the Jupiter Messages building drifted back into his ears, hive-like murmur of a thousand people and machines. Alexis felt twice his thirty years. Most dangerous of all were the times he was not there . . .

He flipped a second switch. “ It’s understood that at present no one is ever to act upon any phoned order from me ?”

“ Yes, sir.”

The tone of the girl’s reply reminded him of the sharp snap in his voice. “ Good. I didn’t think you’d forget.” He let it sound like an apology. “ We must be careful until this affair is cleared up.”

“ I know, Mr. Cutler.”

Alexis unwound his long legs and rose jerkily. His office clock was approaching noon, the hour when communication with Jupiter Central , always uncertain from Earth, was at its best. Over four-hundred million miles away on Jupiter, narrow-beam aerials would be aligned on Earth, whispering across space. The top level of Jupiter Messages was half filled with the equipment necessary to resolve those infinitely weak signals, distorted behind the blanketing inter-galactic static. Jupiter was a frigid wilderness, her gravity nearly unendurable. But where wealth lay, there man went, Alexis reflected. Some even lived to return with their grubbings from Jupiter’s cravassed surface. Alexis stretched his long arms. It was good to be human, he thought, for humans achieved things.

The door opened almost under his hand. Captain Millrow was brisk, small — a dynamited imp of a man. He closed it, his keen grey eyes on Alexis, questioning and uneasy.

“ You’ve had — another call ?”

“ We did.” Alexis did not envy Millrow his responsibility. If anything went wrong in Jupiter Messages, Millrow was the man who had to answer, in the end.

“ You’ve no idea who it is ?”

“ None, except that someone would like to pass himself off as me. There might be complications if he succeeds.”

Lines showed round the other’s mouth. “The danger lies in phoned instructions presumably coming from you. They might get through before we suspected.”

Alexis studied Millrow’s features, noting for the first time the taut lines about his jaw, the quick flicker of his gaze, and the way his dark brows stood thick and tufty.

“ There’ll be no danger of that in future, Captain,” he assured.

Millrow looked relieved. “ I’d heard you’d left instructions covering it. Very wise, with a load ready to leave Jupiter in the coming month.

When Millrow left he seemed more at ease, Alexis noted, and he felt that a point had been gained. Somehow the success or failure of the Jupiter mining project did not feel important, so long as Millrow’s trust in him remained.

Up in the radio room Peter Finn was slowly writing down the Morse that had traversed a large sector of the solar system. Alexis watched him, marvelling that he could pick even the two words per minute out of the welter of noise that had mixed itself with the signal. Peter was a likeable fellow, he thought. Young for such a post, sandy and slight, a trifle lacking in drive, but not wanting technically.

“ Conditions are damn bad,” Peter said.

Alexis nodded, silent because the Morse was only a faint wail beyond rain on a tin roof. Jupiter Central spelled its messages across space six hours daily. For six Earth spelled back, directive elements on the Messages building swivelling to cancel planetary rotation. At noon information on shipments back to Earth had started coming in. The message said there would be definite news within the week. Reading it, Alexis wondered why humanity valued rare metals so. Stored with the nation’s gold, the ingots were symbols only, and never to see use in any machine, ship, bridge or power-plant.

“ So my sister Ruth is being your new secretary, Alex,” Peter Finn remarked, jabbing a stop.

Alexis read the finished sentence, a continuation of the eternal report on local conditions. The Morse paused.

“ She is,” he said.

He remembered Ruth Finn as if recalling a photograph. Quite slight, oddly like her brother, yet with a twinkle in her eyes and a quick mobility to her lips.

“ You’ll like her,” Peter stated.

The Morse began again, and Alexis left the reception room. Peter’s words reminded him that he was not supposed to have met Ruth Finn yet — but had, by chance, in the green park strip ringing the city.

The summer sun was going when he left, taking his car from the parking area behind the building. The vehicle had been delivered there three days before, while he worked, and ran well. Some windows were lit, the building aerials strange skeletons against a pink sky. As the miles drummed by he pondered on motives possibly prompting the infiltration of a stranger into the Messages offices. The voice had first come on the phone when he had returned unexpectedly to fetch something forgotten. Since then he had made a habit of being in the office at unexpected hours.

A twinkling city dawned ahead and he sped through the clover-leaf loop into the main street. Three lines of traffic sped each way; in front a signal flashed from amber to red, halting him before the great north by-pass. The crossing vehicles moved swiftly, thinned, and Alexis found himself staring at a car like his own, but older. In it sat a tall, lean man of his own height and build, a grey felt hat slightly over his brow, the way he himself wore it. The lights changed. He slid forward, a tiny nerve in one cheek suddenly twitching, his back abruptly cold with a feeling of exposure to danger. The opposite vehicle came just as smoothly, drifting automatically through its gears. The driver had his features, Alexis thought. Was high-cheeked, lean, dark-haired too — was him . . . !

The shock of recognition almost brought him into the path of overtaking vehicles. The living image of himself slid by and was gone. Alexis braked, weaving through the lines to the side. A junction gave him space to turn, but he had to wait for the lights again. Past them, his speed mounted, lit buildings streamed by and he searched ahead for the bobbing red lamps of the other. A six-wheel lorry was rolling abreast af slow-moving traffic and he had to wait, fuming. When he licked by the clover-leaf was in sight, yellow lights now bright, and he knew he was beaten. Four roads gave one chance in four of choosing right. He felt the odds too small and turned back for home.

He left the car in the public basement garage, hastened through the lobby, and took the lift to his suite on the fourth floor. The door banged behind him and he stood with hands deep in his jacket pockets, shoulders hunched and cheek twitching. Nasty to find someone spoke with his exact intonation, he thought. But worse to know that man was a facsimile in appearance !

Realisation of the significance of his discovery froze him into motionlessness. The other’s car had been heading out of the city. Where phone calls failed, personal contact might succeed— and might be risked by someone who knew the building well. Perhaps he could have chosen the right road at the clover-leaf, and continued the chase with success, Alexis thought.

He hastened into his study, jerked up the phone and dialled the Jupiter Messages building. The line was dead. He banged the receiver, realised irritation would not restore it to working order, and returned to the lift. He recalled that he had used the instrument that morning and found it working.

The phone in the lobby cubicle operated and within moments he heard the Messages building switchboard girl.

“ Please give me Mr. Cutler’s office.”

Tension made his voice sound a trifle odd even in his own ears. The line clicked, there was a pause, then :

“ Alexis Cutler here.”

Alexis saw his knuckles grow white, and relaxed, fearing the plastic might fracture under his grip. Profanity and blank denial strove for supremity in his mind. He suppressed both and licked his lips.

“ How long shall you be in, Mr. Cutler ?”

He hoped for thirty minutes — just sufficient to get back to the building and confront the impostor now occupying his swivel chair.

“ Only a little while, to attend to something I’d forgotten.”

The lie would pass, Alexis thought. The staff would believe he himself had returned unexpectedly.

The line clicked and he heard Millrow’s voice. “ You wanted an appointment ?”

Alexis swore softly. This was the routine ! Millrow was keeping him talking while young Clive in the basement feverishly traced the call ! The second Alexis Cutler would be sitting back in his chair, face expressing annoyance.

“ Yes ?” Millrow’s tones were honey. “ I’ll be glad to help if you let me know what you want.”

Time wasting, while connection checks flipped back, back — towards his own block, Alexis thought. He stuck the phone back on its cradle, damning the second Alexis Cutler for being clever enough to get away with it.

He was half-way to the car when he remembered the automatic, relic of a boyhood craze, in his study. He could see it, dull black, snug in the right-hand drawer, as if referring to a photograph in his mind. Only a .22, he thought, as he swept up in the lift, but it had split inch planking behind his targets.

The drawer was locked, as he had expected; the key in the desk, as he had known. The automatic was gone. The shock of it stilled him and he sat back upon the arm of a chair, astonished.

It was like a remembered photograph from which the main subject had vanished. His gaze flicked round the room, over window, furnishings and walls. A thief might leave signs.

There was cigarette ash on the carpet near the desk. He sometimes dropped it there, but was sure he had not earlier that day. The ash shocked him more than signs of violent entry. A hurried thief did not smoke, he decided.

He began to examine the rooms systematically, critical of everything until reassured, and a thin doubt grew to certainty in his mind, evoking an extreme unease. The suite had been lived in since he had left for the Messages building. No hurried prowler had come and gone. A chair was moved, a book differently replaced on his shelves. The electric fire set in the hearth was not stone cold, as it would have been if unused since morning.

His second prowling circuit of the study discovered a glint of bright metal under a disturbed cushion. A watchcase lay there, carved, slender, slightly antique in appearance — and not remembered.

He lifted it by the edges and placed it on his blotter, anger changing to triumph. A smooth area intended for initials instead bore fingermarks — not his own.

He thought of the police and Millrow, and dismissed both. The former would ask too many questions and take too long. The latter was best undisturbed — so that the second Alexis Cutler might believe himself safe.

Thirty seconds search in his classified directory brought to light a name inspiring in its commonness and only three blocks away. He put the case in a cardboard box and drove.

The numbered door was two flights up and opened at his knock. Alexis paused. “ You’re Douglas Hopson, inquiry agent ?”

The man was fifty, grey-haired and slightly benign. “ I am.” “You check fingerprints ?”

“ Nothing easier.”

“ Then you can render these visible to begin with.”

Inside, door closed, Alexis parted with the box. Hopson put on glasses and studied it. “ With pleasure,” he said. “ You’ll excuse me.”

He was gone in a second room ten minutes and returned with damp prints large as a man’s hand. Each showed a finger, whorls vastly magnified.

“ Photo-enlarger,” he said. “ Jurymen like to see them.”

Alexis took the prints. Each was so clear the pores stood like black fullstops amid lines sharp as a surveyor’s contours. Only one was slightly blurred at one edge.

“ You could put that aside,” Hopson pointed out. “ Those on the box are best. It was from the case.”

Alexis was momentarily stone. He had wrapped the box in a handkerchief, primarily to keep the lid on.

“ Those on the box ?”

“ Of course — didn’t you want them done as well ?”

Alexis lowered his gaze to the prints Hopson had made, loose now in unnerved fingers. “ W-which were on the metal case, which on the box ?”

Hopson drew them from his grasp. “ They’re marked on the back. Jurymen ask questions like that.”

Alexis spread them on the table, turned them over, examined them again, then realised Hopson was watching him queerly. He paid and went. Outside, he dropped the prints on the back seat of the car. He had not touched the case, except at its extreme edge. He had handled the slick surfaced cardboard box. And the prints on both were the same. He gnawed a lip, and as minutes wore by his annoyance at Millrow softened. The second Alexis Cutler was that good !

After an uneasy night Alexis returned to the Messages building. Only the certainty that no news of real importance would be coming through during the night had kept him away. Let the second Alexis Cutler remain, he thought. He would learn nothing and gain confidence. Confidence fore-ran many a fatal slip.

Ruth Finn had begun work. Efficient, slim as her brother, but feminine, she moved with bird quickness about his office. An admirable specimen of female humanity, Alexis decided. It was good to be human.

She drifted into the background when Millrow entered. He, too, appeared to have slept little, Alexis thought, and somehow he resembled a coiled spring about to jump free. His gaze ceased its darting motion and settled on Ruth Finn.

“ We’d prefer to be alone.”

“ Yes, sir.” She was gone and the door shut.

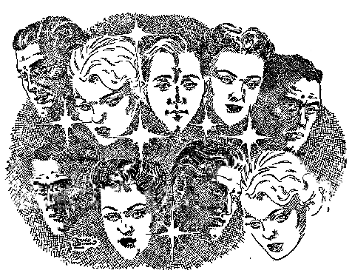

“ You realise I don’t know whether you’re Alexis Cutler — or Alexis Cutler” Millrow said. “ There are few hours in the twenty-four when one of you is not here. Likely enough you’ll meet soon !” Alexis experienced shock, but smiled. “ I hadn’t thought of it that way, but see it’s difficult for you. I’ll tell you exactly what happened last night. Someone’s living in my suite Millrow’s face betrayed nothing as he listened. “ Very similar to the story I was told just before midnight,” he said finally. “ He also said he was sure someone was living in his flat Alexis tensed and his chair creaked. “ Someone was here just before midnight ? Someone you thought was me ?”

“ He was.”

Irritation swept through Alexis. The situation was already so difficult Millrow did not know him from his double. He got up and went round the desk, gripping the other’s arm.

“ Look, I’m Cutler : You’ve known me years. Whoever was here at midnight was the fake

Millrow’s gaze was unswerving. “ You practically repeat what I was told at midnight. But he said, who was here at noon was the fake “ We’ll see about that!"

Easy to say, but not easy to do, Alexis thought. The second Cutler was an image astonishing in its likeness of him if Millrow, shrewd and missing nothing, could not distinguish them apart.

“ What worries me is the apparent lack of motive,” Millrow stated. “ Jupiter Messages has no rival. No one has the brains, money or men for that.”

Alexis still felt irritated. “ From which you deduce — ? ”

“ That the threat comes from outside Earth.”

“ Outside Earth !” Alexis felt as if the words had keyed a reflex of astonishment in his mind.

“ Just so — and perhaps from Jupiter.”

Mixed emotions kept Alexis silent. Millrow’s words showed trust in him, and that was comforting. It was nice to be human, to be trusted by other humans, and by Captain Millrow in particular. But behind the personal satisfaction was a larger unease.

“ Jupiter was devoid of life.” His voice sounded hollow.

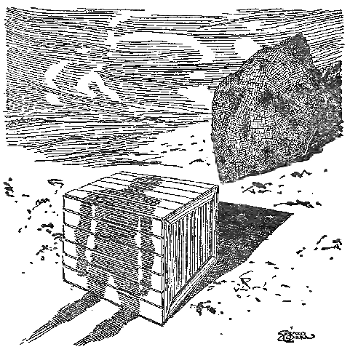

“ Was thought to be,” Millrow corrected. His lips twitched. “ There was a message months ago about life there — at least our men thought it may have been life. Stones that walk — if they were stones. The whole news was suppressed because the facts were hazy. Since then two ships have shuttled from Jupiter to Earth. Others came before— and we can’t be quite sure what they brought.”

Alexis realised that Captain Millrow’s eyes were on him with an abnormal intensity. The Captain’s lips were slightly parted, revealing strong, even teeth set like the jaws of a sprung rat-trap. Resentment came unbidden at the scrutiny.

“ You’re telling me a lot— considering you don’t know whether I’m Alexis Cutler !”

Millrow veiled his eyes. “ Perhaps. Perhaps again, I’m telling you nothing that matters. As I was saying- — stones that walk. Or so they seemed, on a slope where there were stones. Nobody noticed until someone turned up seven crates of stores where there should have been only half a dozen. When they tried to get the lid off one they found appearances were deceptive — it ran back to the other stones and became a stone again. Odd, I think.”

Alexis felt something was expected of him. “ You mean it was

adaptable, a chameleon ?” . .

Alexis felt something was expected of him. “ You mean it was

adaptable, a chameleon ?” . . “So it seems. A first class method of surviving, all considered. Drop in among your enemies or victims, look like them, then — ” Millrow made a sweeping gesture. “ Who knows ?”

Alexis drew a curve that meant nothing on his pad. “ So you think one or more shipped back to Earth ?”

The other’s silence was agreement. Alexis wondered how long Millrow had been working it all out. Jupiter was aged and huge. On Earth, the drive for survival had produced insects like leaves, creatures large and small, weak, strong, weird and unexpected — Man himself. Who could guess at the lines evolution might take elsewhere. A species must survive; all else was secondary.

Alexis got up. The chair felt hard, his long limbs cramped. “ What do you plan- — to lock the second Cutler and me in your basement and see who looks like a teletyper in the morning ?”

“ No.” Millrow’s voice was devoid of amusement. “ A species as successful as this would have intelligence. To some degree its adaption may be consciously controlled. It wouldn’t give itself away. It may even be able to organise its cells to escape detection in any test we could devise. It may be the — perfect chameleon. Or so I’m assuming until I get contrary proof.”

Alexis let his mind wander on the possibility of perfection, and all its implications. How nice, for example, to be a stone sitting safe amid a thousand other stones, or even a packing-case inconspicuous with half a dozen other cases ? But absolute perfection would be more than mere outward appearance. The life-forms of Jupiter might conceivably feel like a stone, or like whatever form they adopted. That would be the absolute end product of protective adaptability, beyond which a million years of evolution could not progress.

He stretched, looking through the window at the aerials on the Messages block opposite. It was comforting to be an ordinary human being and not dwell too much on such possibilities.

Alone, he worked for an hour, half his mind dwelling on Millrow’s idea. Assuming Jupiter’s queer life-forms preferred a planet such as Earth, anyone could see that control of the Messages building would be an important step. Disquieting news could be suppressed, transport schedules discovered.

He liked Ruth Finn and she worked quickly and well, speaking little, and never unnecessarily. Finally he pushed aside the listings of cargo space, weight and value, upon which they had laboured.

“ I saw you on the strip soon after the Penngreen came in from Jupiter,” he said. “ I remember it well because she’d been overdue.”

She smiled momentarily. “ I remember too. It was nice there.”

“ Walk often ?”

“ Quite often, when it’s fine.”

He studied her frankly. She left an hour before noon, her duty finished for the day. He was wondering if he would go to see Peter Finn, enquiring for old reports and listening to what was coming in, when the door opened violently. Alexis stared, astonished, at Finn himself, face white and eyes wide as a frightened child’s.

“ I — I’ve seen Ruth, twice,” he stated.

Alexis pushed back his chair, conscious that the nerve in his cheek was jumping again. “ Twice ?”

“ At the same time !”

Peter Finn backed against the door as if to prevent entry of some ghost.

“ Tell me,” Alexis said quietly.

“ It was during a stand-by period. I was at the window over- looking the entry gates. Ruth went out, turned left, and was hidden behind the shelters where the public transports stop. Half a minute later she came back in the gates. I thought nothing of it until I looked on along the road to see if a transport was coming — and Ruth was walking on there—”

He halted, licked his lips, and Alexis saw the shock had been great. “You made a mistake — ”

“ Never !” The word carried conviction. “ I saw both at once !”

“ It was someone else — ”

“ Think a man doesn’t know his own sister ?”

A man should, Alexis admitted. If two Cutlers, why not two Ruth Finns ?

A sound came at the door and Alexis realised someone was trying to open it. He drew Finn aside, felt him tense as the handle turned. Ruth Finn came in, smiling.

“ Forgot my satchel. Is it here ?”

The muscles were iron hard in Finn’s arm, then shaking. He pulled free, gained the door, and was gone. Ruth frowned.

“ What’s the matter with Peter ?”

“ He’s on duty.”

He studied her, remembering Peter Finn’s words. Ruth, or Ruth, as Millrow would put it ? Twenty-four hours earlier he would have sworn she was Ruth Finn indeed. Since leaving Douglas Hopson’s rooms he was less certain.

She shrugged, searched her desk, and went out. Two steps took Alexis to his inter-office communicator. “ Get me Miss Finn’s home on the phone !”

“Yes, sir.”

He fumed at the delay, jerked up the receiver when it buzzed. “ Hello ?” He disguised his voice. If someone answered who was not Ruth, it might be well they did not know who had rang.

The reply was immediate. “ Hello. Ruth Finn here.”

A question sprang to his lips. He suppressed it and replaced the receiver. It was Ruth’s voice, unmistakable in tone. Yet so had been the voice of the second Ruth Finn. Furiously conflicting emotions and thoughts filled his mind. Which was the real Ruth — she who had worked with him that morning, or she who had come later ? He knew that if his life depended on it he could not decide.

His thoughts were still bedlam when Millrow rang through. “ I’m having a guard put on your door.”

“ A guard ?” Alexis felt astonished unease. It was hateful for Captain Millrow to doubt him . . .

“ Don’t mistake me.” Millrow’s tone was laconic. “ I’m simply afraid that if someone wishes to replace you they may eliminate you to make success more certain.”

“ I see — a bodyguard.”

“ Put it that way.”

The line went dead. Trust Millrow to avoid uncertainties, Alexis thought. If the second Cutler turned up, he would doubtless have a guard too. He grinned crookedly at the idea.

The gunsmith’s door closed with a faint hiss behind Alexis, and he wove quickly through the afternoon crowd. Feel of the .22 in his pocket was reassuring. An outmoded weapon — but one he understood, and readily fatal. As Millrow said, things would be simpler with only one Alexis Cutler, and a man must protect himself. Neither Ruth had reappeared before Alexis left the Jupiter Messages building. Alexis had contacted Millrow briefly, explaining.

“ If either Ruth comes in, I’ll hold her,” Millrow had promised.

Alexis followed streets photographed on his retentive memory. A mile beyond the green belt where he had first seen Ruth Finn was the Jupiter ship site, empty of vessels and topping slightly rising ground dotted with trees. Very easy for something to slip off a landing craft, he thought. Then to cross to the town, adapting to imitate the first life-form found in its new environment. Unluckily for the newcomer, it had overlooked one thing — an animal among others similar was hidden and safe, yet men and women were all different, so that the very exactitude of imitation proclaimed its falsity. For a moment he mused on the strangeness of beings that could be stick, stone or living flesh. It was much nicer to be human, he thought.

He set his back to the Jupiter site. A double task seemed to demand immediate attention: he must expose the fake Ruth Finn, and unmask Alexis Cutler. It was a task he had never anticipated facing.

The sunshine danced lazily among the trees of the belt and for ten minutes he watched people and traffic on the inner city road. Millrow’s bodyguard had not caught up with him again. Some inner perversion and irritation had made Alexis deviate unobserved into a side alley and watch the man hurry amid the crowd.

He phoned the office, and Ruth Finn’s voice replied. He wondered which Ruth she was.

“ I’m going out of town,” he said, “ shan’t be in until late to- morrow morning.”

“ I’ll tell Captain Millrow, Mr. Cutler.”

“ Please do.”

He' rang off, glad all was in order so that his lie seemed to have been believed completely. He would wait a full hour, he decided, before returning unexpectedly to the Messages building.

Afternoon sun was warm on his back as he entered at the gates. He paused momentarily, enjoying the feel of it, pitying creatures condemned by circumstance to be stones on some frigid slope. The building hummed with usual activity, hub about which the Jupiter project rotated. He sought Captain Millrow’s office at once. Millrow’s gaze rose as the door opened and simultaneously his hand went to a desk push.

“ I thought you were upstairs,” he said.

Alexis closed the door softly. “ Why so ?”

“ Because I had this very moment been speaking to your office.” Millrow released the push. “ If it wasn’t you who answered — ”

“ It must have been my double.” Alexis felt keen satisfaction.

“ He’s being watched ?”

“ It must have been my double.” Alexis felt keen satisfaction.

“ He’s being watched ?” “ Of course. You slipped your guard.”

Alexis shrugged. “ He missed me. I wasn’t sorry. How about Ruth Finn ?”

“ We’ve got them both below !”

Satisfaction again flooded Alexis’s mind. With two Ruth Finns side by side action would be possible. A sound outside the door told him Millrow’s signal had not gone unheard, and he was glad. Self-protection was a strong element in human make-up, he thought, as was common sense.

“ Well have them up one at a time,” he said.

The next hour was a species of hell. The first Ruth pleaded ignorance of the whole matter, swore, once, and wept, at the end. She had modified her regular hours because Mr. Cutler had asked it. Yes, she had realised something was amiss when she found her work was being carried on in her absence. White-faced, she went at last.

The second Ruth was equally certain. She did not understand how they could doubt her. No— her expletive was brief — she wasn’t a fake. How could they suggest it ! A little later she sat with tears on her pale cheeks, but adamant.

When both had gone Millrow sat on his desk gnawing a lip. “ Damn it,” he said, “ they’re the living image of each other ! I’d have sworn the first was Ruth Finn — until I saw the second!”

Alexis paced the room. With matters standing thus it seemed he might have to shoot the second Cutler first, and explain why after.

“ The imitation is as good as the real thing,” he said flatly. “ Can Peter Finn identify her ?”

“ No. I’ve tried that.”

Millrow took to pacing jerkily. He scowled from the window, fiddled with his desk, grunted, then halted, face brightening with inspiration.

“ Whoever’s the fake is pretty efficient at it!” “ Very efficient,” Alexis agreed.

“ A perfect fake in appearance — and feeling !” Millrow slapped a hand on the desk in triumph. “ A fake that didn’t trust itself would always be in doubt and uncertainty. Its own unease could betray it. Others, genuine members of the group it had joined, might sense that unease and attack it.”

Alexis nodded slowly. “ There’s much in what you say. Where does it lead ?”

Millrow’s fist rose, one finger pointing like a pistol. “ The most efficient , perfect alien fake wouldn't know he was a fake !”

It sank in slowly and Alexis acceded the Captain was right. Adaptation so perfect as to simulate fingerprints — so absolute as to have at its disposal even the memories of the person imitated ! Partly unconscious, so that the fake took its place among the crowd as if one of them, believing itself to be one. That, indeed, would be the end-product of survival by adopting a place in a host society ! The knowledge was a shock. He imagined the being of Jupiter existing as stones, on the dim borderline of unconsciousness, while centuries passed. Aeons before perhaps there had been strange living animals — creatures they could imitate. But all had passed away, leaving the spurious with no models but the stones on the slopes. Alexis shivered involuntarily. How terrible would be their situation ! He was thankful to be human, one of a noble race on a warm, fruitful world.

“I’m not letting Ruth or you leave this building until the thing’s cleared up,” Millrow said.

“ You take a grim view of it.”

“ Very grim ! Where two have come, so can others, I’ll not have Jupiter Messages used as a focus for the arrival of shiploads of — ” He sought for a word, but abandoned the effort. “ Call them what you will — this thing must be stopped at its outset !”

Alexis turned his gaze through the window. The sun looked very pleasant. “ There may be a way — with the second Cutler and myself. If it works, you could try it on Ruth.”

Millrow grew still. “ How ?”

“ Have him in here, and I’ll show you !”

While Millrow used his desk communicator Alex stood with chin on chest. Plainly the Captain could not keep them all prisoners indefinitely. But one thing had so far been overlooked — the real Ruth and Cutler would have the wellbeing of Earth at heart, while somewhere in the hearts of their imitators would lie a greater regard for self, born of the desire for survival. All beings longed to live, hated to die . . .

Alexis Cutler, as Alexis thought of him, looked thin and a trifle tired when he came in. His back to the door, he studied Alexis, his brows drawn down. The silence grew, tension mounting, and a nerve on his cheek twitched.

“ So we meet,” he said. “ You’re the man who stole my new watch- case the day after I bought it, lived in my rooms, and took delivery of my new car !”

Alexis stirred uneasily, noting the eyes could never be cruel. Nor could his own. “ My rooms,” he said. “ Naturally I’ve lived there. As for the car — I’d been waiting for it months.” He snorted. “ If an interloper leaves something in a room he’s entered he can’t accuse the occupier of theft !”

The armed silence grew again. “ Quarrelling over little points won’t help,” Millrow put in tensely.

Alexis nodded. “ As you say, it won’t.” He considered his words, choosing carefully. “ I didn’t bring him here for that. My point is very different.”

The second Cutler watched him. “ Then let’s hear it.”

“ You shall.” Alexis felt that triumph was his. “ Humans are noble — brave. A man will die for his fellows, for Earth.”

Millrow’s eyes flickered, his attention so intense his breathing was halted. Alexis saw uncertainty and a small fear arise in the gaze meeting his own.

“ A man will, as a rule,” the second Cutler admitted.

“ An infiltration of alien beings, once organised, would be exceedingly dangerous.” Alexis chose his words with care, pressing remorselessly to the point he must make.

“ Deadly,” Millrow whispered.

“ So to be prevented — even at the cost of personal sacrifice.” His gaze did not stray from the eyes like his own. “ You have a .22 I believe. Place it on the desk.”

He withdrew his own, holding it by the muzzle. The other .22 was exactly as he had expected from the image rising in his mind.

“ Take both, Captain Miilrow,” he ordered.

Miilrow did, hesitating. He backed, facing them, eyes showing he already guessed the part he must play.

The second Cutler followed the movement. “ I’ve had that gun years. Any reason why I shouldn’t carry it ?”

“ None,” Alexis said. “ That’s not the point. But this is — one of us is a fake, and must die. Captain Miilrow doesn’t know which. Men are noble, and will die for Earth.” His voice rang. “ So, Millrow — shoot us both.”

This, he thought, was where the second Cutler would begin to break. Alien, fake, he would not be willing to die for Earth ! The fear was already bright in his eyes, and his cheeks white. One cheek twitched and he licked his lips.

“ As you say, men will die.” Low words, emotion filled. “ So — shoot us both !”

The two muzzles rose and from Millrow’s expression Alexis knew he would carry out the order. There was no other way, and Millrow was a soldier. Two muzzles trained on two breasts; two forefingers contracting slowly . . . This was the final moment, Alexis thought. The alien must break. Fear was bright in the second Cutler’s eyes and dew had sprung to his brow. Yet with the fear there was a measure of bitter triumph.

Seeing it, Alexis wondered, moments drawn out with expectancy. Men were noble, he thought. Men were noble. His brain screamed the words as he longed for the second Cutler to snap, his control to go, so that the tension could be ended. But the other was straight as a ramrod still, unflinching, waiting.

Under the bedlam howling in Alexis’s mind another thought grew, forced up from below. This was not self-preservation any more, but self-destruction ! The whole point of adaptation and imitation was continued life. Now, imitation was bringing death. From lower levels of his mind a clamour grew, warning him . . .

Then the cells formed into eyes began to lose their organisation, and processes beyond his control took over, fulfilling their end — -to preserve life. With his last fading vision he saw two men, one upright and noble, one holding two guns, but gaze now fully on him . . .

He strove to speak, but no words would come. Only in his mind did the phrase ring. I thought I was a man. It had been nice to be human. But better be a living stone than a dead man. I was a man, Alexis thought. The knowledge meant little, fading with the host of adopted memories taken from the first human he had seen when leaving the Jupiter ship. Seeing was gone; hearing was gone. From deep levels of his sentience feelers reached out, discovering the form and nature of objects nearby. Adapt, adapt and live. A quiet, semi- conscious tranquility came. Nice to be a strong wooden desk, he thought ... It was safe to be a desk.

George Longdon.

pseudonym of Francis G. Rayer.