Country of first publication: Great Britain (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland).

This work is Copyright. All rights are reserved.

A segment of this story appeared in SLANT No 5 in 1951, as "Eve of Tomorrow".

Only machines roamed the Earth — searching, searching — while underneath the Sleepers waited for them to rust.

Illustrated by CLOTHIER

The dim rock tunnel ended at a thick glass door against which the boy pressed his nose. Beyond, under long illumination tubes, stood in shadowy mystery many rows of bunks and he gazed, fascinated, at the silent figures, each with hands clasped upon its stomach and covered with a white sheet, and at the cables and tubes which rose from the headpiece concealing each face to the ceiling-high gloom. A thin humming filtered through the thick glass door, but inside nothing moved. The bunks extended out of sight in receding perspective, each with its covered figure and descending leads. A whisper of slow footsteps came along the passage and he started away in guilt.

“Here again, boy ?” The old man was fragile and stooped, with many wrinkles and a beard of glinting white silk.

The boy looked down, evading the reproving eyes. “It’s so — lonely,” he said.

The other nodded, his hairless head an egg that could not reach equilibrium. “Yet why look in upon them ? It is not prudent.”

“Why, wise one ?” Eager blue eyes looked up into the sad, aged grey. “They sleep so soundly ”

“That is our danger — we must not envy them.”

A frail hand fell upon the lad’s shoulder, guiding him away. “Come. I will tell you the story.”

The boy nodded eagerly, hastening so that the hewn corridors and empty chambers echoed to his feet, and to his quick voice and thousand questions. They traversed the long corridor up which he had crept to gaze at the Sleepers and went into a room with two bunks. A bulb glowed overhead, lit by power he knew was generated below, for he clearly remembered the deep chambers where enormous automatic mechanisms whirred sleepily. The old man closed the door and sat upon the bunk.

“I was once a lad like you,” he said slowly, “except that I had dark hair and you have blonde. You, in turn, will open the door and wake a child, who will come to manhood as you grow old, learning all you tell him.”

The boy was wide-eyed with wonder, though he had heard this story many times before.

“You’ve been into the Chamber of the Sleepers ?” he pressed, his hands tightly against his sides on the bunk with excitement.

“Yes, once. There is a key which you will see when you are older. But remember that the door is double and that compressed between its panels lies a gas, so that to break it is death.”

The boy nodded. “The story,” he urged. “Tell me the story again.”

The old man smiled. “When I was young I, too, was impatient. I walked these halls and chambers, going curiously to the glass door and through all the tunnels. Who had made them, I wondered, and why ? What lay behind the far limits of our passages ? Could the rock go on for ever infinitely ? An old man was with me, and when I could read I learnt many new things. I was so eager for knowledge I would scarcely leave the library. When I was fifteen I was given the key to a shut room and I learned strange, unbelievable things.”

He shook his head heavily and the boy fidgeted with excitement. These words hinted at new secrets to be unfolded. “I am nearly fifteen,” he breathed.

“True, lad. My tutor said that he, too, had once been a lad, with an old man to teach him, and that the old man, in his turn, had said that long ago he himself was a boy, with a helpful, wise old man as companion. In the locked room will be instructions to be read by none but you. When the year draws near you will arouse one of the Sleepers, but your loneliness must not hurry that day, nor must you forget, leaving humanity to die.”

The boy frowned. “Humanity ? Many people ?”

“Yes, many like you and I,” the old man said. “Once there were many people so that each had a name. You will learn of such things. At first I did not understand, but understanding came. So it will with you. Many people thronged these halls, but they had not lived here always.” He stopped with great emphasis.

The boy was silent with wonder. He realised that at each telling a tiny

fragment was added to the story, so that he should learn slowly and understand

fully.

“Once these many people walked fields and towns, seeing the sky and feeling the sun upon them.” The aged voice grew dreamy. “They saw the sun and the heavens ”

“You use strange words !” Wriggling with the fear that he would not understand, the boy bounced upon the edge of the bunk, his blue eyes wide and his face anxious. “Tell me what these things are like !”

The old man shook his head sadly. “I have never seen them, but there are pictures in the locked room and you must be patient, learning all in the fullness of time. Once, my guardian said, there had been an apparatus, a machine, with which things above could be seen. He had never used it, for it was broken, but he said his tutor spoke of it. One day I will show it you, for there are many things you must begin to understand. Other places exist. There is the great above where the many people were, and vast beyond our understanding, for a man could travel for many days and not reach its end, not even if he had a machine to ride such as you will see in the pictures, and which went with terrible speed on wheels and in the sky.”

He was abruptly silent, listening. The bulb dimmed ; the undertone of the generators below sank in diminuendo and the boy was still. Before, but seldom, this had happened. As always, he saw the old man’s face grow pale.

“The warning,” he breathed, aged limbs shaking.

The boy was motionless except for a tiny involuntary tremor, remembering he had been taught that he must always be still when the light suddenly dimmed and the generators whirred at their lowest, quietest level. Sometimes they waited many hours, sometimes only minutes. In the dimness he could see the old man trembling, and in the silence hear his own heart’s beat. Above, perhaps half imagined, was a heavy scraping as of the movements of some ponderous body beyond vast thicknesses of rock. Minutes passed; the sound grew inaudible and the generators began to turn at normal speed. In the increased light the boy saw that sweat glistened on the old man’s face and that he looked very tired.

“It was — them, lad,” he said.

His voice was hushed and the boy trembled.

“Tell me more,” he breathed.

“No, you will learn when the time comes. It is a terrible knowledge, and I am tired. You must prepare our food.” He began to rock himself slowly on the bunk, his hands tight between his knees and his head bent so that his beard touched his chest. His cheeks were grey and the terror which had come as the sound scraped above seemed to have robbed him of strength. Once before he had lain upon the bunk, breathing heavily, the boy recalled, then had lifted his head and touched a thong about his neck.

“If you ever find me asleep, not waking, lad, take this key.” His voice had been a sigh in the room. “You have often looked upon the door it fits, asking what is beyond. Take it, open, and learn what lies there. Remember your duty is great. You must not fail. Now go, for I must rest.”

The boy had gone through the winding passages to a great steel door.

Behind, the old man said, was stored terrible knowledge. The boy longed to

enter, afraid yet fascinated, but understood the time had not yet come.

Afterwards he had crept away to gaze at the Sleepers, then, tiring of even that,

had gone into the room the old man called the children’s library, which had

been opened to him when his fifth birthday had come.

Now, as he prepared the food from coloured jellies and stringy substances hard to the teeth, he thought of the old man’s words, wondering what the broken apparatus could be. Until recently he had accepted life as he found it, eating, sleeping and learning, but with each passing year the legends from his companion’s lips interested him more and more, filling him with a wild, strange excitement. It all seemed some fantastic fairyland of which the old man spoke: some strange myth passed on by word down the ages, half unremembered, half unbelieved, yet evoking a poignant longing, and often bringing melancholy into the old man’s eyes and voice as he talked on.

“What are — they ?" the boy asked as he took in the meal.

Tears stood in the old man’s eyes. “It is a terrible knowledge, lad, and you are young. Forget while you can. Afterwards we will see the machine of which I spoke.”

They ate, facing each other in the hewn room with a single bulb above. Once, when it had ceased abruptly to shine, leaving the room so dark the power of vision might have ceased, the boy had changed it, bringing a new one from the store the old man had shown him.

“All the machines work by themselves ?” he said, half questioningly, as he chewed a succulent vegetable which grew in warmed tanks below.

“Yes. They are self-controlling and very delicate, rarely needing adjustment. One day you may see them, but they are behind great glass doors and we must not walk among them. Many wonderful things are there, and a great clock with a huge hand. Legend says that when it has turned full circle the Sleepers will arise, but the Library tells nothing of that. It was told me by my tutor, but may be untrue.”

He became silent and the boy thought of the long rows of Sleepers, glimpsed through the door, each so completely still. Once, long before, he had noticed that one white sheet was stained and crumpled, rotting away into ribbed ruin, and that moisture dripped from it to the floor. He had called the old man, who stared through the glass panels, nodding sagely, and at last shuffled away.

“It is nothing, lad,” he said. “When I was a boy there were two, far away down the right hand line.”

The boy had not forgotten, and had crept back, peering awkwardly through the door. Just visible where the old man had said were two bunks where lay no neat shrouded forms, but odd, skeleton shapes like many fingered bone hands resting with their tips together, and protruding through tattered sheets. Not understanding but feeling uneasy, the lad shivered and hurried away.

After eating they went along a tunnel dimly lit and narrow and into the

high, wide room where the broken machine stood. The old man gazed at it,

stroking his beard pensively.

“My tutor said that once this machine showed a whole strange world above. He did not know on what principle it operated, except, except ”

He hesitated and the boy prompted him eagerly: “Except what ?”

“That it caused a curvature in light-rays.”

The old man became silent. Disappointed, the boy walked round the contrivance. A lens pointed upwards, surrounded by upright, slender rods, and before the machine was a cubicle. Visible inside the octagonal framework were upright burnished cylinders large as a man and connected by a bewildering intricacy of leads and tubes to each other and to apparatus below.

“Have you tried to repair it ?” the boy breathed.

The old man shook his head. “It is beyond comprehension. What could anyone do with such a machine ? We are helpless, and the ancients are not here to show us. I only know what I was told, and that one must stand in the cubicle in darkness, to watch.”

“We could find what is broken !” the boy declared.

The old man shrugged unbelievingly. “Try, it is a harmless pastime. I am too old to ponder on such things.” He withdrew, and his slippered feet whispered away into the silence of the corridor.

The boy returned to the machine, hung his long outer garment, warm but hampering, on the cubicle door, and examined the apparatus minutely while the clock in their sleeping-room marked many revolutions of its hands upon the slowly mounting row of figures in a long, thin window above it. He did not understand the working of any part of the machine, but studied it carefully and at last came the moment when he found a tiny, bluish crystal tube from which projected three silvery legs. Yellow leads went to each outer leg, but the broken end of a red lead was poised a nail’s thickness from the other. Excited, scarcely breathing, he inspected the other crystal tubes spaced round the core of the machine. All were exactly the same, but the red lead was joined to the centre leg on each.

For many long moments a strange fear and awe came upon him, then he carefully twisted the end of the red lead on its tag. Trembling, he went into the cubicle and to the large switch the old man had shown him and drew it down.

A slow murmur awoke in the machine and a violet radiance played in the cubicle, slowly clearing so that the boy held his breath. For a long time nothing seemed to happen, then the cubicle became abruptly blue. Irregular greyish fluffy shapes drifted across it, rising slowly upwards, and a line of undulated brown came into view low down. The boy gazed, wide-eyed, and the brown, blue and fluffy shapes slowly began to pass away to the left. Far, far away on the very edge of the screen something moved, growing closer and clearer as the scanning rotation of the beam reached it and he stared in amazement. Abruptly he turned away and went running down the corridor.

The old man came hurriedly, muttering that it must be one of the “terrible ones,” but gazed in astonishment. The boy thought the thing moving there oddly beautiful, and hung on his companion’s words.

“Unbelievable,” the old man breathed at last, and his voice shook. “It is a woman, a woman . . .”

Steel shod boots scuffed rhythmically through the peppery hills, leaving a

winding trail in the saffron dust. Eyes stared ahead at the yellow plain,

unmarked by movement or the artifice of men, or turned, sometimes, to

look back, following for a moment the long trail which snaked across the

slopes, up a valley, and from sight where the ochreous horizon met the sky.

Away to the left, pole-like and corky, stood the remnants of old woodland.

A delicate ear turned towards it, but no birds sang in the dead trees, no creature

stirred under them, no man or machine moved among the brittle, fossilised

trunks.

The feet went on, and the sun cast ahead the shadow of a beautiful woman, fine of face, firm and graceful of muscle and limb. She altered her direction slightly, and soon her shadow fell across the torn roofs of empty buildings nearly buried in the drifting brown particles. She paused, as if wondering what past knowledge of men lay buried here, hidden for ever as the sterile earth sifted into the great libraries of the world, then went on. A light wind moaned over the undulated brown, raising tiny eddies, and she began to hurry. Since growing things had relapsed their tenure upon the earth fearful dust-clouds often raced upon the screaming wind, so that a dark twilight came at mid-day and the sun was hidden. The poisoned, dusty soil rose many miles into the air, sweeping fantastically across whole continents. Rivers ran brown and no fin stirred in their polluted depths, or in the seas, tinted with the same noxious death.

Her footsteps came to a stream, and she halted. No plants grew upon its barren banks and the swirling brown water held no life. She followed its course, going down upon the plain, eyes searching always for something that lived.

Farther on, a crumbling town lay empty, the wind-driven sterile soil up to its second floor windows. She went through the tall buildings, upthrust through the dust like the relics of some ancient city, listening always, her eyes never still. Beyond a great building the curling wind had drawn away the all-pervading dust; the bonnet of a vehicle showed, and scattered bones, white in the sun. A newspaper flapped, uncovered by odd chance, yellowed and crinkly. She bent, touching the sheet lightly with gloved fingers, but it crumbled like a dry, fragile leaf into nothing.

She went on through the unpeopled city. Soon night would come, and she stopped, taking from her back a satchel made of thin chain-mail and lifting out a book. With a pointed instrument which left a blue line she wrote upon the thin steel pages.

The sun sank; a brilliant moon shone across the dusty hills, leaving clear-cut, inky shadows, and she went on. Once a sharp, clear crack came echoing through the night and she turned towards it, walking until she found herself among the sticks of a dead forest. Another bough broke, scattering a thin mist of fine earthy particles, and she turned away, her face expressionless . . .

The sun shone brightly as she approached a steel dome upon high rocks.

Blown earth lay piled against one side, but the steps were half clean and she

mounted slowly, her shod feet loud upon the naked rock. The dome had

windows, and a sliding door which stood open, leaving a trickle of dust in the

crack in which it rolled. She went in, looking each way, said “Do not be

lonely,” then stopped. No one was there. An eddying wind had swept dust

in and it was undisturbed.

For a long time she stood motionless, listening to the sigh of the wind, now rising. Soon the poisoned, dusty soil would obscure the sun and silt into greater obscurity great buildings where lay the whole knowledge and history of mankind, unread for uncounted years.

As if at a loss and having no activity-pattern to respond to this, the unexpected, she stepped backwards. One steel heel caught in the groove in which the door slid and she fell backwards, jarring down the rocky steps. There, her head opened like a compressed tin-can; tiny wheels and electronic tubes sprang out and lay on the dust. One foot twitched, then she was still, her machinery silent, the mechanisms of her cogitation halted.

The rising wind swept long trails of dust across the peppery hills; a tree snapped, but no eye saw it fall, and no ear heard it, or the piping gusts carrying the saffron dust high in the obscured sky.

Eyes tingling from concentration, the boy had watched the figure pass from

sight, walking quickly. Only then had he dared operate the controls which

guided the seeing ray, but night came. Even when the cubicle showed dawn

he could not find her and he left the machine feeling hungry and disappointed.

During the following days he often returned, but did not see the figure again. Once, on the rim of vision, a great shape moved, almost obscured by flying dust, yet massive and terrifying. He called, but the thing was gone before the old man entered the cubicle, nodding sagely at the description.

“One of the terrible ones. They tear the earth as with a devil’s claw, and once, legend says, thrust their sting into the very heart of all man, so that he ran, screaming, but could find no refuge. In those days wise men said that the terrible ones would run with fire and tumult until there were no more men.”

“What are they ?” the boy whispered.

“I do not know, lad.”

“But the great library ?”

“It tells nothing of them. I only know what was said by my aged tutor, and that had been related to him in his turn. The terrible ones tore the body of living men, he said, and the rivers ran red and cities burned to the lowering sky. Happiness was no more, nor green, nor did any living things move in all the air, upon all the land, or stir in all the waters of the earth.”

“But the woman,” the boy pressed eagerly.

The old man shook his head in puzzlement. “They would wish to kill her, . with the last sons and daughters of all men, leaving earth a wilderness where no living thing moves.”

“They move,” the boy pointed out.

“They move,” the old man agreed, his face grey under the single bulb. “But legend says they do not live.”

He was silent and the boy saw that he had learned all the old man knew, but a restlessness came upon him. He left the cubicle door open and thought of the world above, of the slender figure walking through the dust, and of her danger, and knew that he must go up.

“You have never been above ?” he asked as they ate before sleeping.

The old man shook his head as if very tired. “Never; it would betray the

whole remnant of living man, the legend says. The beasts on the hills are

quick as an adder, and powerful, and long to spread their poisonous gas upon

all men. My tutor was told how we must wait, guarding the Sleepers, that

perhaps one day when the clock has turned full circle the reign of the terrible

ones will be ended.”

As he concluded the light dimmed; the engines far below droned softer

and the burrowings were hushed as with fear. Immeasurably distant, like

the scratching of a homy insect on thin metal, sounded a slow scraping and

the earth vibrated as with the passage of some huge body.

The old man’s face was grey and moist. “They are coming more often,” he breathed. “Do they suspect ? If they find us there can never again be any more men.”

He trembled and his suppressed terror communicated itself to the lad, who shook as with ague, gripping the bunk. He thought of the beautiful woman and the extremity of peril threatening her and knew that he must go up to the surface, whatever dangers his act caused.

After many days he learnt that there was a way up, prepared for the Sleepers, but that it had never been trod since they had filed into the earth and lain down to dream. No one should know of it, the old man told him; it was secret knowledge of the Sleepers. But when his tutor had entered the Chamber to arouse him to his duty one of the Sleepers had been moving upon his bunk, the apparatus off his face, and had talked of a door and a tunnel, thinking the hour of awakening had come. Afterwards he had died, white with terror. The old man tried to point out the bunk, but it was so far from the glass door they could not see its emptiness.

The boy found the door through which none had ever been. Thrilling strangely he hurried back, calling, but the old man did not answer. He was still on his bunk, his hands folded on his chest and his eyes closed. The boy shook him, calling loudly; then was abruptly silent. For a long time he sat looking at the old man, whose white beard jutted up, then everything he had been told began to return like whispers in the room.

“When you find me asleep, not waking, take the key. Afterwards carry me to the little steel door at the end of this corridor, drop me through, close it.”

He took the thong and placed it round his neck; for a moment the key was

cold on his chest. He lifted the old man, astonished at his lightness, and carried

him to the steel door. Open, it showed a narrow, black shaft leading downwards to where red glowed as from everlasting fires. He slipped the body in,

watched it disappear with a sudden swish, closed the door and went away.

He walked the corridors, trying to escape from his own loneliness, often halting to listen for the old man’s slippers on the rock. He ate, slept, and awoke knowing that his plan to go up could now be soon fulfilled. Perhaps the woman would even come below, to be his companion, so that they could be safe, and neither lonely . . .

As he prepared the old man’s voice seemed to echo faintly there, as if his spirit still lived and strove to give a warning.

“The terrible ones are formidable beyond all expressing. They strive to discover where the Sleepers lie. Their aim is unchanging beyond man’s understanding, their power great. They see with a vision outside the spectrum used by men, and move with a life not like ours. They spin endlessly at their work; never hasten, yet are never slow, though seasons wax and wane across the world they never tire.”

The door was secured by a means he could not understand, but after two long periods of work he burrowed round it. Ahead was a passage, rising slightly and extending farther than his light penetrated. He withdrew over the fragmented rock to get food and contrive a haversack.

The tunnel was long and old falls made piles upon the floor. A fault sheared the way so that he had to scramble down a rubble-filled funnel on cut hands and knees to gain the floor ahead. Many hours came and went; his eyes ached from staring into the blackness beyond his torch beam; his legs hurt and twice he sat down, eating and moodily wondering if the tunnel ever ended. Often he crept over loose rubble, a broken roof near his head, but at last blue showed and he emerged upon the higher slopes of a great hill, startled, amazed, and with his eyes streaming from such light as he had never before seen.

Down the hill unroofed buildings made squares in the billowing dusty

brown; behind them a haze of flying particles rode the breeze he felt on his

cheeks. Beyond the swirling wisps shapes moved, enormous and grotesque

and he shrank back into the hole in fear. They were dissimilar in size and

form and as the dust thinned he saw they moved around a spidery tower

pointing high into the obscured sky. Then the wind grew keener; dust flew

higher and the scene was hidden from view, though his ears caught an

intermittent high-toned note, audible across the whole valley and setting chill

fingers on his spine.

Feeling hidden by the rising dust he went over the hill, squinting against

the flying particles, which made a deep brown twilight. Half way down the

opposite slope the air cleared abruptly and the configuration of the hills was

familiar. He searched eagerly but found no footprints, then went rapidly

down the hillside and across the plain.

The sun shone on a metal dome, silted round by blown dust. There was no movement; no one came to greet him, nor did any sound break the quiet. He walked round slowly, noting that at one place hewn steps had led up to it, but now merely descended from sight into the powdery soil. The dome was a hundred paces round, and a sliding door stood open near the steps. Blown earth made a long ridge against the interior wall, and he entered.

The brown dust lay everywhere. Inside the door feet appeared to have disturbed it, but he could not be sure because the wind had driven in a new layer. The interior was divided into sections, each, he thought, equipped just as if a man had wanted to live there. One door was fastened and would not open. One gave access to a room containing a machine like that below, another, to a workshop. The last swung wide at his touch and inside there was less dust, a bed, a mirror, and books, and a few pictures on the wall. One was of a lad, brown-skinned and tall ; clear-eyed, lean and blonde. The boy looked for a long time, still with amazement; looked in the mirror, then again at the picture. He knew, then, that he was not mistaken : the photo showed himself. The frame was aged, dry as cork and immeasurably old. He sat down upon the bed, looking at it, not thinking because the power of thought had momentarily flown.

Wind sang round the dome. The boy went to the door, but choking

particles raced by, sweeping from the barren hills. For long hours the wind

piped and drummed as upon a tambourine, swirling its brown earthen fog

past the open door and reducing visibility to a single pace. Night came, and

still the wind sang. The boy slept, and awoke at early dawn to find that the

wind was gone. The air was clear and from the door he looked down a score

of hewn steps. The dome stood on an up-jutting rock, bared now of the

surrounding dust and at the bottom of the steps lay a form, still half concealed.

He ran down, dropping to his knees to scrape away the dusty earth. Then he saw the limbs and head, and sat back upon his heels, his frantic attempts at rescue ended. The woman was metal, polished and beautiful, yet with a split across her skull and a sight of tiny, compact electronic machinery, choked with soil.

He stood up, fear conquering disappointment, as he remembered the old man’s words. Was this machine a trick of the terrible ones ? He looked round quickly, trembling, but all was silent. No sound came across the sterile hills; no shapes moved in the brilliant sunlight, or in the long, sinuous shadows.

He retreated up the steps, hiding until he should decide what to do. He searched again and was confronted by the closed door. He would get behind it. he decided; he could not leave without knowing what secrets lay hidden.

He found tools and began sawing through the lock, until after an apparent infinity of work the steel parted. He wiped his brow and opened the door cautiously. It had fitted well and only a faint haze of dust lay on the floor inside. Opposite, sitting upright in a steel chair, was an old man with golden hair and a combed beard. He was dressed in thick brown material; his face and eyes expressed pleasure and he stood up, stepping forward so that his feet rang on the steel floor.

“Do not feel lonely. Master,” he said. “The Sleepers live, and therefore you are not the last of men. Let me talk, for I am wise.”

The boy started back, remembering the woman, and terror, very real but with its cause incomprehensible, flooded through him. The old man followed him through the door, walking rhythmically. The boy saw that one knee of his garment was crumbled away to fragmented fibre through some touch of damp or mould.

“I will talk, Master,” the voice promised, following. “I will talk of the past, when the Earth was quick with living things or of the present, when the worst days are upon us, or of the future, when the Sleepers arise.”

Still he approached, and the boy halted, quivering. “Stay where you are !”

“As you wish, Master.” He halted, the voice unchanged. “Do not despair; remember only that the Sleepers must be guarded. All else is nothing. Be tranquil. Master. Talk with me, or order, that I may fulfil.”

The boy stared at the metal joint visible through the torn garment, and at the radiant face.

“Tell me of the Sleepers,” he whispered.

The old man beamed. “Little to tell, Master. They will arise full of

wonder, but your sons are among them, each in his turn to guard them,

keeping his secret until the last library is opened, and treating as a son each

brother who comes next. In them lies salvation for men.”

The boy’s thoughts spun as down a precipice and a hundred tiny memories

which had meant little came back. The old man’s loving care ; the similarity

of eyes and features ; the myriad controls in a small room at which he looked

each day, sometimes making infinitesimal adjustments. Once, when very

tiny, before such things had become so familiar that he disregarded them, the

boy had questioned him. “I work that the Sleepers rest long and soundly,”

the old man had said, his eyes grave. The boy shivered, remembering the

bunks where the sheets lay in unclean ruin.

“The Sleepers cannot sleep — untended ?” he breathed.

The face before him beamed. “Not with safety. Master. But they are cared for, until the Awakening. Be easy, Master.”

“How long have you sat there ?” the boy whispered.

“Merely moments, Master. For me, all eternity is an instant. I do not grow old, nor, resting, do I eat. Even you, Master, once said I was as our terrible enemy, who can wait while men grow old and die.” He beamed, and the boy felt sick at heart. “While the Sleepers are safe we need not fear our enemy,” the voice droned on. “ ‘Protect them, my sons,’ you prayed. ‘Upon them shall depend all that is to be of man, and whether he become but a word now never spoken on an empty Earth’.”

Protect them! the boy thought. He sprang down the steps and began to run across the undulated dusty earth. Only when he was on a hilltop did he realise how vain his search must be, for no footsteps remained. The dust-storms might have obliterated the tiny tunnel entrance, which could be anywhere on the convoluted hillsides, where the dunes seemed to march from dawn until night, and where little waves stood in irregular corrugations, breathing from their peaks tiny wisps of brown powder.

He searched until nightfall without finding the tunnel, then sat down upon

the dry, dusty earth and wept.

He awoke to find the old face, a beaming mask in the moonlight, bending

low over him.

“Master, one of the terrible enemy is coming.”

The boy rose, listening. Far away sounded a mighty scraping like a giant dragging his feet on iron.

“There is — danger ?” he asked, scarcely breathing.

“Death, Master.” The old face beamed at him. “Come away. We must hide.”

“I cannot find my way to the Sleepers.”

“No one knows it, Master, so that, not knowing, they cannot betray. Only you live here. If there were other men they would not know, for they might be tortured and free their secret. There are no records, for the enemy might discover them. Even when you made me you did not tell me where the entrance was.”

The boy looked at him, frowning. “You mistake me for someone

else!”

The old man teetered on his feet as if not understanding. “Come away,” he said, and began to retreat towards the dome. The boy watched him, but when he reached the moonlit top of the rise his rhythmic steps faltered. For a full minute he stood motionless, face beaming, stiff as a pole, then abruptly folded like hinged levers into a heap. The merest line of thin smoke began slowly to ascend.

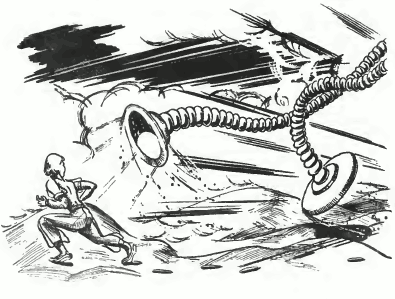

The boy listened to the dull scraping, approaching up over the hill beyond the toppled form. A huge hump showed, with long arms like bat’s wings with no membrane folded each side. One arm reached out, rolling the still form over like a child’s toy. The arm withdrew; the hump slewed, rising over the hill.

With a vigour born of complete fear the boy began to wriggle down into the dusty earth until he was almost concealed, a mere elongated hillock amid the many vales and ridges of blown soil. Head strained frantically sideward's, he watched.

The shape came over the hill and the earth shook. On its back two saucers

wide as the boy could have spanned with outstretched arms swayed slowly as

if endeavouring to locate anything that moved upon the hills. The sides of

the object were low upon the ground, concealed caterpillar tracks churning

up a thin wake of floating brown motes as it came down the hillside. The boy

scarcely breathed, seeing that if it did not change its course it would come

directly upon him. Gaining speed, it seemed to fill all the sky and purred

gently ; was gigantically wide and awesomely huge, and at the last moment the

boy started up from his hiding place, his limbs trembling as if already crushed.

Crying as he ran, he sprang up the hillside, looking back often.

The gigantic saucers rotated slowly, oscillated, and faced him. The shape

slewed, flinging soil high, following and gaining momentum, its bat arms

extended, casting long, grotesque shadows. He ran on, stumbling, panting,

changing his direction often, his heart pounding and his hands outflung

like those of a person in a nightmare. Soon he lost all idea of direction;

there was only the curving hillside, the loose soil silvery in the moonlight, and

the following enormity, always nearer, its saucers following every movement.

He scrambled up a steep incline where the rock had been swept bare, paused

on the top, lungs heaving, and looked back.

The thing came on, treads flinging rubble high, inner machinery snarling.

The boy screamed, turned, slipped, and found himself in a narrow rocky

cleft. Thunderous sound came up the incline and a dark shape halted above.

A jointed arm moved and one saucer projected over the side of the cleft,

moving in a searching scanning sequence. Sobbing, he heaved himself

under the thing and to its rear on hands and knees, reeled to his feet, hesitated,

and sprang, lying flat on its back trembling.

The thing came on, treads flinging rubble high, inner machinery snarling.

The boy screamed, turned, slipped, and found himself in a narrow rocky

cleft. Thunderous sound came up the incline and a dark shape halted above.

A jointed arm moved and one saucer projected over the side of the cleft,

moving in a searching scanning sequence. Sobbing, he heaved himself

under the thing and to its rear on hands and knees, reeled to his feet, hesitated,

and sprang, lying flat on its back trembling.

The surface was completely cold and his trembling subsided as the vehicle moved slowly twice along the full length of the cleft, one saucer projecting over the edge. Then both saucers rotated slowly in synchrony, scanning all the hills. For a long time came only a low whirring, then the machine turned down the incline, retreating, and he knew for the moment he was undiscovered.

As they rolled forwards, rising and falling to the dunes, he began to search the back on which he rode with his eyes and fingers, every movement infinitely cautious. There was a trapdoor; his fingers found fastenings and with a start he realised they were of a type which could only be operated from the outside. He wondered what that meant, then slowly began to work them loose. When both were undone he gathered his muscles so that he could fling back the trap and enter with one movement, and shot down feet first, toes kicking until they met a ladder, where he clung, drawing the trap shut. The machine had not halted. He spun round ; found that the interior was illuminated weakly and deserted. A narrow footway stretched from the ladder. He passed between panels of unknown purpose, and came to the end. There were no seats ; no places of any kind where any man or creature could sit or rest, to operate the machine. There was only the narrow way and ladder, and, each side, masses of apparatus. Abruptly he realised the machine was empty because it had never been intended that any man or creature should ride in it.

Momentarily stilled with wonder, he clung to the ladder, his body swaying to the motion, his ears filled with the drone of the motor and the intermittent sounds coming from unseen controlling mechanisms.

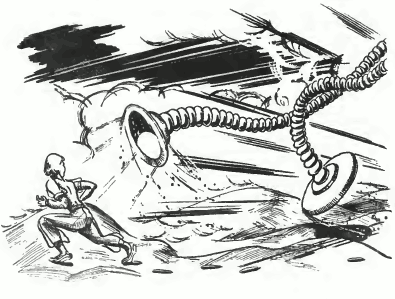

Eventually motion ceased. He mounted the ladder and peered through a narrow horizontal slit made by slightly opening the trap. Vehicles of vast size and great diversity of form almost surrounded him, some built as huge containers, others armoured, with strange weapons projecting from their sides, and from rotating turrets upon their backs, where, on each, a metal rod stood. Some resembled that in which he was hidden, and yet others were fitted with tubes with fine nozzles. All lay still in ranks and he saw that many vacant spaces existed in the lines, and that some vehicles were rusted and clearly inoperative. One container was corroded to a shell. Dark fluid had run from it, eating a fissure in the vehicle’s side and staining the earth for many yards around. Far ahead was a spidery tower topped by aerials.

He looked the other way and saw he was at the edge of the concourse of machines, noting that except for a faint humming the one in which he was hidden had ceased activity. The saucer scanners faced the distant tower as if awaiting some signal. He lifted the hatch and wriggled out, lying on the cold steel. Nothing happened and he slithered to a tiny platform, and from there to the earth, pressing his body flat against the back of the machine. He stood for long minutes, only his eyes moving, and noted that twenty paces away a dip ran obliquely up across the hills. Satisfied, he sprang forwards.

In the shadow, sheltering trough he hugged the brown dust, listening. No sound of wheels whirring in pursuit came and he began to scramble along, keeping the earthen rampart between himself and the machines. Only when he had laboriously ascended and crossed the first low hills did he rise to his feet.

Brown dunes lay ahead, and judging this the direction he walked on quickly, often looking back and listening. When two ridges of hills were behind him he sat down to rest and eat a little food from his pack. The brown dust had filled his boots; he emptied them and surveyed the dunes critically. The dust was fine, dry and powdery; only where the wind had removed it was rock revealed. His feet tingled and the dust seemed poisoned and sour, as if blended with noxious chemical traces. When his food was gone he would starve, he thought sadly.

He halted at the next hilltop, ears straining. Far ahead was a voice,

upraised, yet unintelligible from distance. He ran towards it, feet sinking

with each step, and passed over a ridge. Ahead was a shiny object flat on its

back and babbling at the unheeding sky. He slowed, disappointed.

The beaming face gazed up; one metal leg did not move, but the other bent and stretched, scuffing a deep furrow.

“Do not be lonely, Master, though on all the earth are only the fighting machines made to battle against men. Remember you have caused the Sleepers to lie at rest until our enemy has rusted into nothing and have sacrificed your sons to guard them. You are not responsible for this sterility. You did not want poison sprayers, nor individual-seekers to terrorise our enemy.”

“You mean my father,” the boy said, but the face still beamed and the boot scuffed as if some interior fault prevented comprehension.

“The day will come, Master, when the son who is blond like you, among all the sons who were dark as their mother, shall grow to manhood, and the Sleepers awake, and return upon the earth, bringing grain and the animals which sleep with them.”

The boy touched his head, knowing it blond. Abruptly the figure began to wail upon a shrill note.

“Woe if the Sleepers are untended or awake with our enemy still on the earth ! Woe if they arise and our enemy has not rusted to dust, for they will be slain. Woe if the mechanisms falter, so that the Sleepers die terribly under the earth !” The words ran faster and faster. The boy sat on the poisoned soil, not listening, but wondering at what he had heard. He gazed at the dome, knowing no one would be visible there. Innumerable seasons had come and gone since his father had inhabited this refuge, apparently spending his whole life trying to destroy the enemy. At last the wailing grew thin and the smiling form was stilled.

For two days he sought the tunnel entrance without success. He returned

to his sanctuary, examining its scanty contents anew, and finding a book of

thin metal pages covered with blue writing. Filled with an odd wonder, he

sat down to read.

“Jan. 9th, 2091. Finished erecting pre-fabricated sections. Dome is immobile, therefore machines will not attack. Stores lamentably insufficient.”

“Feb. 17th. Machines all day yesterday spraying slopes of hills east. All grass and herbage yellow to-day and trees shedding leaves. Spraying vehicles still working beyond hills.”

He turned several sheets to a date five years later. “April 2nd. Saw no machines; went to hilltop. All visible terrain yellow. Dust clouds bearing poisoned soil are beginning as summer approaches.”

“May 29th. Was chased by individual-seeker, but gained dome. Machine halted outside.”

“June 3rd. Machine still there. Dare not go out. Working on robot to do light tasks and reduce loneliness.”

“June 10th. Machine went away. Read all day to robot speech-recorder. Can think of no new means to defeat machines; they retaliate fiercely when attacked. Consider initial plan best. When the Sleepers awake the machines will surely be worn out . . .?”

The boy shivered involuntarily, leafing through many closely-written pages.

“Jan. 17th. Air all day filled with poisoned dust. Assume little vegetation anywhere exists to retain moisture and soil. Remember self-motivated poison-sprayers were sent into all four major areas of war. Substance used enormously potent.”

“Feb. 5th. Wish I had not stayed here alone. Always remember it was Feb. 5th Committee decided machines should have no radio-control so that enemy could not jam signals or gain control when machines were near.”

“Aug. 6th. This was day first fighting machines returned, and could not be controlled because our transmitter had been bombed. Remember panic and own people running through streets, though so long ago . . .”

The boy saw he was nearly twenty years from the date of the first entry.

“Dec. 25th. Had Mobo read to me all day. Very tired. Fear illness. Viki completed. She works well.”

“June 2nd. Went to hilltop overlooking marshalling point of machines. Radio tower obviously inactive. Machines return here from each foray in accordance with pre-set controls. Went too near and was chased by individual-seeker. Its one track was faulty and it could not maintain straight course. But must be more careful.”

“July 1st. Wish I could reach radio tower, repair it and radiate signal halting machines activity. Machines pre-set to respond to signals from no other locality. The Committee’s safeguards to prevent enemy gaining control of our fighting machines too complete and damnable!”

“July 7th. Dust storm arising. May try to reach tower. Committee should never have devoted whole productive capacity to self-controlling war machines, leaving humans defenceless. Hope to transmit code signal halting machines if tower can be repaired.”

It was the last entry.

That night a storm exceeding in severity any the boy had seen began; wind drummed on the dome and powdered earth flew in choking clouds. Day was a mere brown half-light and slipped imperceptibly into darkness, when the wind fell, until dawn brought a clearing sky with only puffs of dust dancing across the hills. The silence became oppressive and the boy wished the cherubic robot had not collapsed. He went into the darkened cubicle of the light-bending machine and played with the controls. The storm had created new ridges and up to the farthest range of the apparatus they stretched in arid dunes devoid of living thing or the work of men. He focused upon the marshalling point and saw the machines waiting there still, rank upon rank in thousands. But the radio tower had collapsed in the storm and was half hidden in the dust. As he saw it, a growing hope born of the last diary note died. He frowned at his father’s photo, immeasurably old, then he walked round the dome, glad the wind had hidden the metal woman, whose one arm had begun to wave unceasingly as if seeking help. Night came, clear and cool, clouds hiding the moon, and he ventured to the top of the nearest hill, listening for the approach of any machine which might destroy him.

A luminous shape was coming up the slope without sound. An odd, irregular cone, scarcely as large as he, and ghostly. It was approaching smoothly and must pass close; he hesitated, then stepped forward to intercept it. It came nearer, as a phantom cloak, and he reached for it. His hand passed through. Completely without sound, like the projection of a moving picture, it went on in a long, gentle curve, receded down the hill and from sight. He stared after it, eyes wide, wondering if it could have been some figment of his tired mind.

He sought the dome but could not sleep, remembering the ghostly movement of the object across the hills. Midnight had gone when realisation came with sudden shock. It had been an image of his coat upon the cubicle door of the machine in the cavern! Astounded, bewildered, he tried to reject the knowledge, but at last decided he could not.

He puzzled until dawn. The machine bent light, he thought. Normally, two-way vision existed over straight paths, but it made the paths parabolic, and the apparent movement of the hanging garment was caused by the scanning motion of the apparatus, which still functioned. The cubicle should be kept in darkness so that the watcher would be unseen, but he had left the door open and light filtered in from the tunnel.

He entered the cubicle of the machine in the dome, closed the door and

switched on. The war vehicles round the ruined tower showed as through a

powerful telescope, the sun shining on their weapons, tracks and turrets. For

a long time he stood in the dim cubicle watching them and thinking

deeply.

Evening shrouded the hills when the boyish figure appeared over a rise,

his blond head shining, and walked towards the silent fighting vehicles.

His steps were light and his arms swayed as he came like a wraith along the

slopes. An individual-seeking machine below awoke to life; its saucers turned,

followed him, and its tracks flung back pulverised earth. It lurched into life,

gaining speed, its gigantic metal arms reaching out.

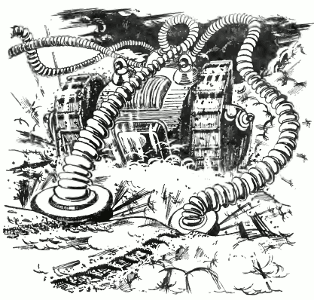

The boy walked on, looking at it, gliding with unhurried steps straight towards the many ranks of machines. An armoured fighting vehicle awoke, its turrets turning to follow his motion and its scanners rocking, conveying information to the complex mechanisms inside. The individual-seeker was very close, running like a mighty beast with outstretched claws. It grasped at the figure, seemed to miss, and was carried past by its momentum. It slewed, its saucer scanners rotating to discover its prey, walking on across the plain.

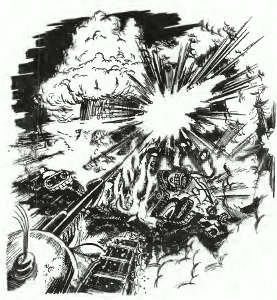

The fighting vehicle arose in thunderous life; simultaneously its turrets began to hammer out sound and mighty bolts erupted vast clouds of earth about the boy’s form, leaving smoking craters to testify to the awesome power of each missile. Still the wraith moved on, now among the machines themselves.

Silent hulks rose into activity and for long hours guns burned red across all the plain, sending up clouds of smoke which were illuminated fitfully from beneath. Through the holocaust the boy walked, while engines snarled and vehicles pirouetted, spewing destruction at the riven soil and at each other as they clashed at short range, or at the ghost that walked unharmed amid the fury. Explosions made the heavens quiver; the night shone bright with the fury of weapons, and rang loud with the scream of machinery and the clangor of destruction. Always purposeful, sometimes changing direction, the figure walked through the smoking havoc while missiles rained awesomely around him and tracks churned great furrows across the shivering hills. The sky echoed and a great cloud of smoke drifted slowly on the wind. At last, when dawn was near, the sound decreased; the sun came up upon a silent earth where a figure stood like the wraith of a nether world . . .

Swaying slightly, dizzy from marking time for many long hours, the boy switched off the lights he had fitted to illuminate the cubicle and went outside the dome, sitting abruptly on the top step, exhausted.

Silence overlay the distant hills, where smoke rose sullenly. Spent, he slept, his back to the open door, awaking only when the sun came warm upon him. He went over the hills and gazed upon the chaos of ruined machines. Only one gun turret followed him, but the vehicle was on its side, its tracks twisted, and the weapon did not fire. Awed by the vastness of the destruction, he withdrew, to halt, his face suddenly alight. Men and women were coming up out of the hill . . .

THE END

Francis G. Rayer.

[Reading note: Logan's Run which pictured a ruined world with people emerging from underground was published in 1967. Logan's World pictured a people living underground with unusual population control].