Eager young eyes stared at him. Bill looked at the floor. Mark’s

words had been odd. I'll know what it’s like out there. Only that

morning Major Kenigan had risen at the staffroom table like a man

about to drink a toast.

Eager young eyes stared at him. Bill looked at the floor. Mark’s

words had been odd. I'll know what it’s like out there. Only that

morning Major Kenigan had risen at the staffroom table like a man

about to drink a toast.

With world population increasing steadily year by year the problem of feeding the masses becomes more grave. If machinery can solve the problem might not Man’s mind need an antidote to the overwhelming cacophony of sound such machines would entail?

Illustrated by QUINN

Bill Ashton sat with his elbows on the breakfast table and thought that Judy was as beautiful as when he had married her eleven years before. Smart, neat, bright, she was what he would call ideal womanhood.

“Mark had the nightmare again last night, Bill,” she said, suddenly.

He realised that she had been quiet, perhaps worried. “Over-trying his brains at school?” he mused. “Sometimes they push the bright ones.”

Judy shook her head. “Don’t think it’s that. He’s almost top of the age group class. They haven’t pushed him up with the eleven-year-olds.”

“Doesn’t seem worried about school?”

“No.” Her voice was convinced. “Always glad to go. Never complains.”

Such was his own opinion. Bill thought. Mark was a good all-rounder, clever at most things, including sport. Not the sort to be bullied, or get scared of failure.

“If it happens again we’ll take him round to have a check-up.” he suggested. He got up and kissed her lightly. “Don’t worry.”

Outside his flat, lofty in a ten-high block, he let the spring air flow into his lungs and the sun bathe him. Many men would envy him, he thought. At forty, he had a home and family to be proud of; was strong and sane; got as good pay for being 2nd Assistant Computer in the Computer South Block as any man of forty could expect, and liked his work. Who wanted more?

He noted it was early and took the slow external lift. A glass-walled cube, it sank down past the seven lower floors. Plants and shrubs grew on the balconies. People were astir, bright, cheerful inhabitants of a bright, cheerful city. There should, he thought, be no reason why anyone should have nightmares.

As he descended he thought of Mark. Perhaps it would be as well to look in at the New General as he passed. Dr. Young had been sympathetic before; had said, “If your boy gets these night-mares again, Mr. Ashton, don’t hesitate to tell me.”

Young was in his office examining case-papers and put them aside, rising. He shook Bill’s hand. “You’ve become quite a stranger, Mr. Ashton.”

Bill wondered why it was that something in the other’s manner hinted his visit had not been unanticipated.

“It’s about Mark, doctor.”

“Ah, your boy.”

That, too, seemed almost an anticipation. Bill thought. He sat down.

“He had nightmares before, doctor. They’re returning. I wondered whether it was perhaps — perhaps hereditary.” He hesitated. It was hard to say. Harder, still, to fear that Mark might grow up having to combat the same — unevenness of mentality that he, Bill Ashton, had fought all his life. An unevenness that was shown in one way only : by certain nightmares . . .

Dr. Young shook his head. “No fear of that, Mr. Ashton. You’re sane as any man. Psychoneuroses like yours aren’t transferable to offspring.” He pyramided his long fingers under his lean chin. “He’s always taken his tablets regularly?” “Yes. At least I think so. We’ve been trusting him to take them himself, lately.” Bill felt a new fear in his heart. “He’s not — not epileptic, doc?”

“No.” Young’s voice rang with confidence in his words and the backing of medical science. “His electroencephalographs are wholly normal. Check that he’s taking what I ordered. If the trouble recurs, let me know at once. You’d be surprised how many similar cases I have.”

Bill rose and left. He strove to remember any incident in Mark’s childhood that could have caused any irrational fear, and failed. They must hope Mark would grow out of it.

Outside, he hurried on towards the Computer South Block. Though the city was calm and beautiful, there was no room for drones. Everyone worked according to his skill, training and ability. In the Computer Block a hundred units always stood hungry for data, calculating the factors of production, economy and efficiency.

Major Kenigan, Head Computerman, was already in the cream and chrome halls, each as silent and aseptic as a hospital room, except for a faint background hum, just audible, as of a thousand scribbling mechanical fingers. Scribbling fingers there were, Bill thought. But the scribblings were ephemeral cathode-ray traces, automatically photographed, or the jewel-pivoted, temperature-corrected pantograph arms of the differentials.

Brisk, perhaps fifty, Kenigan’s uprightness told of his military training. His hair was grey, brushed flat, his face lean as a youth’s.

“I’ve a special series for you to set up, Ashton.” He strode across the floor, feet ringing on the metallic surface. “Berry is away — another case of stress illness, I suppose.” He snorted his annoy- ance and pushed through swing doors.

“Bad?” Bill asked. Berry had been a good man. Stress illness — neurosis — simple inability to face everything. Call it what you would. Shell-shock, neurosis, crack-up. All the same.

“Don’t know yet,” Major Kenigan stated crisply. “Report on him isn’t in.”

They passed through into the vacant setting-up cubicle and

Kenigan opened a folder. “Here’s the problem — ”

Alone, Bill began to translate the data into terms comprehensible to the computer mechanisms. Long figure series and fractions into bi-numerals; intelligence and stupidity factors into graphs; hopes and faces of other men into irregular dots on spooled paper . . .

He worked automatically, his mind on Mark. Then thoughts of Mark drifted, his brain concentrating on the data, drawn by a score of isolated facts which meant nothing, when isolated, but which might mean something, when co-related. After an hour he was no longer working abstractedly, but with close concentration, plotting sheet after sheet and filing them into the machine.

Unexpectedly a sheet from a scribbling pad appeared between two pages in the data folio. In Chris Berry’s scrawling hand was written: All nightmares —

Bill froze, read it again, screwed it into a ball, and abruptly left the cubicle. Outside, in a wall niche, was an inter-room communicator and he dialled the co-ordination desk. The girl’s reply came soon.

“I wish to enquire about Chris Berry, of Computer South Block,” he said.

“Yes, sir?”

“When did he go off sick?”

There was a long pause. “Late last night, sir.”

Bill remembered the marking on the folder he was handling. “Had he been working exclusively on the XC71C series data?”

The delay was longer. Finally her voice sounded. “Yes, sir. He had begun, but abandoned the work, feeling ill.”

“That’s all you know?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Thanks.”

He returned to the cubicle. Just begun, perhaps. Chris had just begun ... it might mean anything, like the note. Or nothing . . .

It was late when Bill rode the elevator to his 8th floor flat. At midday he had dined in the Block Staffroom, going out only to call Judy.

“I looked in on the Doc on the way up, Judy. He says Mark’s most likely all right, but we’re to see he doesn’t miss up on his sedatives. Maybe it’s just over-excitement — ”

Her reply had been relieved. Now, as he opened, the door her voice sounded again, this time more annoyed than he remembered hearing it for years.

“It’s for your own good, Mark ! ”

The half open second door gave a sliced view of the next room. Mark stood by the window beyond which the city lights flashed. His face was set in a scowl — and that, too. Bill seldom remembered seeing.

“Don’t see why I should take it, mum.”

“It’s for your own good, dear.”

“But — Mark seemed to struggle for words. “But — Sam at school says it — if I don’t take them I — I’ll know what it’s like out — out there — ”

The last words came with a rush and the boy’s hand indicated the window. Bill stepped through the door.

“What’s this?”

“He won’t take his sedative.” Judy’s voice had a note of helplessness.

“I don’t want to, dad!”

Eager young eyes stared at him. Bill looked at the floor. Mark’s

words had been odd. I'll know what it’s like out there. Only that

morning Major Kenigan had risen at the staffroom table like a man

about to drink a toast.

Eager young eyes stared at him. Bill looked at the floor. Mark’s

words had been odd. I'll know what it’s like out there. Only that

morning Major Kenigan had risen at the staffroom table like a man

about to drink a toast.

“All our past, all the struggling, striving and building up, that was like spring, Ashton,” he had said. “This is summer now. Mankind’s summer. Out there is our reward.” He had indicated the window. “A fullness, a plentitude — ”

The words had stuck in Bill’s mind. Mankind’s summer. A glowing, glorious summer grown from the spring of striving. Yet Mark had shuddered when he had said those same words, out there.

Bill licked his lips, suddenly dry, and closed the door quietly. “Try to tell me what you mean, son. I want to help.”

But from the look on Mark’s face he felt it would be hopeless.

“It — it’s only what Sam said, dad.”

“That with no sedative you’d know what our city is really like?”

“Yes.”

Bill drew him round to face the window. The daylight was fast going and mellow street lights snapping on. “And what do you see, son?”

Mark hesitated. “Streets. Lights. It’s quiet. Somewhere there’s music — perhaps down by the sea front — ”

“In short, a nice city — -?”

Mark nodded emphatically. “Sam’s just a silly,” he stated with conviction.

Bill tucked him into bed. For a long time he gazed from the window of his own room. A bright moon rode through tranquil clouds that only hid the stars in patches. The city did not sleep, but was quiet. It was beautiful, restful — and an ideal city in which to live, he thought.

It was an hour before he turned in, and sleep came easily . . .

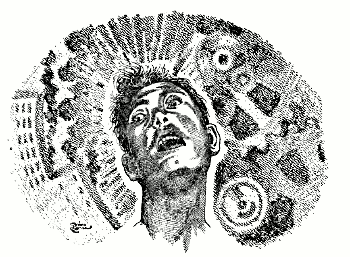

He awoke clutching his ears. About him the city screamed, howled, vibrated and roared with a torment of machinery. The walls shook. The ceiling was like the underside of some huge engine. Burnt oil made the air stink and rumblings tore at his eardrums. He reached blindly for a sedative capsule, kept near his bedside for just such an occasion. Damn, he thought. The last nightmare had meant a psycho and change from his usual sedative to the next higher in the list. This could mean he’d not got clear of the trouble, as he had hoped. It could mean another psycho, another change ... or was it that he had forgotten his evening tablet, talking to Mark?

Tranquility spread through his veins as the rapid-acting drug took hold. Sweating at the memory, he lay in the dark, trying to recall what had first caused the nightmare. He could not remember. Its first coming had been long ago, beyond the limit of remembering, in childhood. It was always the same. Terrible while it lasted. Terrible. He wiped his face. Gone had been the peace, the quiet room, the nice city. Instead was a city wholly functional, wholly mechanical, roaring, screaming with a million machines. And it always seemed so real. That was the worst of the nightmare, when it came. It was so real.

Perhaps he should tell them at the hospital on the morrow, he decided.

It was early morning when he opened the door to a man six feet tall, lean and yet knobbly as a cactus. The sight banished some of the fatigue from his mind. “Chris! Thought you were hospitalising ! ”

Chris Berry made a face expressing disgust. “They gave me a shot and told me to have a week off. Said I’d been over-working.”

Bill saw the look in his eyes. “You’re not resting — and are a man overwork would never kill.”

“Perhaps.”

Bill closed the door, somehow glad Mark and Judy were still in bed. He had risen early, worrying.

“You’re working on that special series,” Berry stated. "You’ve read it?”

“Only half. Takes some setting up.”

The other relapsed into a chair. “Only half. You’re lucky. I ceased setting up and read the lot.”

His eyes were haunted and Bill hid his growing tension. He closed the other door unless Mark or Judy should hear. “Not many men could do that, Chris. It would mean nothing — ”

“To Kenigan, for example. Though he’s alright at his job.”

Bill nodded. “He sees that we work.” He knew that he was wilfully avoiding the uppermost thought. He let the question come.

“You read the series?”

“Yes.” Berry rose, walked needlessly round the table, and sat down. His face twitched. “I got two kids,” he said.

Bill looked for the connection of thought and was afraid to find it.

“Boy and girl, aren’t they?”

“Yes. And both have nightmares ! Both have since they were born. They were practically born having nightmares, and have had nightmares ever since! Why?” He jerked a finger at Bill. His cheeks were white. “Why? Answer me that! Is it natural? There’s no cause — or seemed no cause.” He halted, licked his lips. “You got a boy. Bill. Does he — ”

Bill nodded slowly. “He does.”

“And you?”

The room was silent a long time. “I also, Chris.”

They stared eye to eye. Berry drew in his lower lip.. “Listen,” he said. “I have nightmares too— and the same one my wife and kids have. I read that series, too. Cut out exact calculation and mathematics, it means that we and our children are not alone — ”

“Not alone?” Bill could only refuse to understand, echoing the words to gain time.

“No. That series covers such experiences. Far as I read, it tabulates abstractions covering five hundred thousand people.”

Bill’s breath hissed. “The population of this city!”

“So I believe.” Berry unwound his knobbly knees. Two spots as of inner fever burned on his white cheeks. “They called it stress illness,” he said bitterly. “Heaven help us! ”

The emphasis of his words remained after he had gone. Bill stood on the balcony, watching the cage descend. The city was cool, fresh, quiet with morning, her five hundred thousand people only beginning to stir. He scratched a cheek. Five hundred thousand cases of stress illness. Or, put another way, five hundred thousand nightmares ... It was surely impossible.

He got a drink and decided to look in on Mark. The boy sat with a book propped on the coverlet. He started, guiltily, tried to conceal the volume, recognised he was already discovered, and looked rebellious.

“Couldn’t sleep much,” he said.

He placed the book front down on the bedside table. The action was too casual. Bill picked it up and nibbled a lip.

“An odd book for a lad, Mark.”

“Sam lent it me.”

Mark’s playfellow. Bill sat on the bed. “Where would he get a book like this Mark?” He put a finger on the title: Post-Hypnotic Suggestion and Use of Drugs in Obtaining Persistence of Illusionary Suggestion. Below the long title was the author’s name : Dr. Emanuel Zeker.

“He had it from an uncle — ”

Bill slid it in a pocket. “Think I’ll see what Zeker says myself,”

he said.

An hour later he left the flat and descended to the awakened streets. A public vehicle bore him to the centre of the city, and to the entrance of the public library, mellow and clean in the dawn sunlight.

He passed through the silent halls, ignoring the 3D books, the illustrated stories, the vividly presented text-manuals. In the back of the library were old histories, travel books and volumes in flat printing and he followed them to Z. There was no book by Emanuel Zeker. The library catalogue showed many volumes under Z, and three by Zeker. His interest stirred and he sought the librarian.

“Are all Emanuel Zeker’s books out?”

The man, white-haired and stooped, examined him. One finger on his desk depressed a button. “You are interested in his work?”

“Of course.” Bill somehow felt the man was intent on wasting time. “I’d like the volumes when they’re returned.”

A door behind the desk opened and Bill met cool grey eyes, wide-set in a strong face, as a man came through.

“We’ll discuss that elsewhere,” the man said crisply.

So the button and delay had meant something. Bill thought. Two other men, equally erect as the newcomer, equally military in bearing, came through the door, round the desk, and halted. The grey eyes flickered from them to Bill. “You’ll come with me? I am Commander Renton. The name may be familiar. I wish to ask a few questions— merely routine — ”

The voice was authoritative, factual. The others moved smartly and Bill found them each side of him.

“As you wish. Commander.”

They marched through the halls, down a corridor, and into a private room. The door closed and Renton stood alone by the desk.

“The library has no books by Emanuel Zeker,” he murmured.

“But the lists ...” For the first time Bill let his surprise show.

“We find it a convenient method of knowing if anyone wishes to read Zeker. They find no books, and naturally enquire.”

“But Post-Hypnotic Suggestion — ”

The grey eyes grew intense. “So a copy still exists!”

“Certainly, but ...”

Renton silenced him with a gesture. “It will be destroyed.” He pondered. Big in body and brain, he obviously had the character and mind to think for himself.

“For various reasons we like to know when anyone is interested in Zeker,” he said more evenly. “As a point of interest, he has been dead this several hundred years, but his observations are not out of date. For various reasons which I cannot discuss, I most strongly recommend you abandon your search for his further works, or anything connected with them or him. I repeat — most strongly recommend ...”

Bill looked round the office. It could have been a prison, he, the prisoner. “You arose my curiosity, Commander Renton,” he said.

Renton sighed. “I was afraid the warning would do just that. You look the type. But there are things it is better not to know.”

“Such as . . .”

Renton considered his finger-tips, then looked up. “Perhaps if I tell you a little it will make you give up this search. How shall I put it? Let us say that — that things are being made a trifle easier for people, and that it’s best it should remain so.”

Something in the other’s eyes halted Bill’s questions. The silence grew until Renton slid from the desk.

“My men will show you out.”

Outside, Bill wondered at the words. Things are being made a

trifle easier for people ... It was an odd thing to say. In his heart

stirred a deep and inarticulate uneasiness. Such words could mean

many things.

That day he almost completed setting up the series Major Kenigan had given him. He admired Chris Berry’s ability, born of long computer work and aided by something akin to genius. The data, by their very numbers, were effectively incomprehensible to a human. The multitude of facts hid the overall picture. But to a minute extent Chris Berry had seen through the mass of information, discerning a shadow of its meaning. In a city of five hundred thousand there were five hundred thousand cases of stress illness — so called.

How and when had it all begun? He decided that evening should be spent trying to find out. There were approaches other than through Emanuel Zeker.

With evening, the library was busy. Bill wandered among the children and adults in the self-talk and 3D book sections, and passed the sprinkling of students seeking information. Only half-a-dozen people were in the history room and he settled down to search. If there was a beginning — an abrupt transition from normality to the present circumstances — some record of it must exist.

He systematically waded into the past, choosing social history as the best line. Fifty years before, the city had been much as it was. A hundred years before, very similar. Two hundred years before, basically the same. Two hundred and ten years before — he frowned, his grip creasing the old fiat-type page.

Two hundred and ten years before there had been much discontent, apparently justified. It centred on working and living conditions. Buildings were too cramped, work too regular, food too monotonous. He turned back the pages slowly. Leaders had arisen, tried to better conditions, and failed. At the root of it all was one cause : production. Things once luxuries for the few became regarded as necessities by the masses. Wages rose, production rose, buying power rose — above all, the complication of living rose. Mankind was becoming swamped in his own productions, and ousted by the factories necessary to pour out the goods he desired. Natural resources failed, making roundabout methods necessary. Every city was a factory-swamped chaos.

He turned on again. “The installation of the great new computer will undoubtedly better conditions,” the historian had written. “Many commercial processes may be shortened, better methods found. Human happiness must be put above mere production.”

Ten short years after, the city had become virtually a paradise, the book claimed. But it did not say how. Bill compared passages and decided the later sections had (been prepared by a different author.

“Still interested?” a voice asked.

Bill raised his head and met cool grey eyes. Renton’s gaze dropped to the page.

“No, I haven’t followed you. It was chance — half a guess, half hope — ”

Bill closed the book. “Hope?”

“That you’re tough enough.” For long moments Renton studied him, then he sighed. “Maybe I’m guilty of wishful thinking. Maybe, perhaps, it’s simply best I do my duty.”

Bill froze. “Your duty?”

“To warn you again. Forget Zeker. Forget history — especially that period.” A finger tapped the closed volume. “If not, you may regret it.”

“You’re making threats,” Bill stated.

“No, Ashton, only statements. Other men have puzzled over Zekor — and history and bitterly regretted it. You have a wife and boy. For their sakes, forget it.”

Bill rose jerkily, face flushing. “You threaten them!”

Renton sighed. “No, Ashton.” He suddenly looked very old. “But, as you love them, let this matter rest ! It is you who would threaten them — you — ”

He dropped silent, breathing heavily. His breathing subsided and the spots of hot colour went from his cheeks, leaving him impersonal as before.

“Tranquility is worth a lot, Ashton. Your tranquility — that of your wife and son — everyone’s tranquility.”

He turned smartly and strode from the history room. Bill watched his back pass from view beyond the doorway, grew conscious of his tensed muscles, and relaxed.

What had the historian written? “Human happiness must be put above production.” In an odd way the phrases fitted Renton’s parting words. Yet production had certainly not eased. In many processes bewilderingly roundabout methods were required to make up for lost natural resources. Elements had to be manufactured, instead of scooped by the ton from natural strata. Oil there was none, nor coal, nor metal ores. Mineral beds were exhausted. With infinite pains metals were reclaimed from the waters of the sea. No Bill thought, production had not lessened. Every human being had every material thing he could want.

When he left the library it was quite dark except for the tasteful city lights and a rising moon. A breeze fanned his cheeks, coming in from the sea. The past winter has been short and mild,

scarcely noticed, more an affair of weather bulletins than personal

experience. Now, summer was approaching. By day the city

glowed under spring sunshine neither too hot, not too bright. By

night moonlight lit the peaceful street bringing rest to the city’s

workers. He thought of Berry. Chris could have made a mistake.

No single human was infallible.

A mere block away Chris Berry trembled at the nightmare surrounding him. Fumes obscured the reverberating night sky and all

the heat and stinks of a thousand chemical and factory processes

caught his lungs. Stars there were none, nor moon. The city

howled and shook, screamed and wailed, wolf-like, machine-like.

so that he was a mite in the heart of a vastness of spinning

wheels, whining bearings and flaming mechanical wrath. He

clutched his ears, praying to awake. Stumbled, shielding his eyes

against the fiery glows projected against the sulphurous sky. He

fell, fingers scraping the filthy road. He wept, consciousness going.

A mere block away Chris Berry trembled at the nightmare surrounding him. Fumes obscured the reverberating night sky and all

the heat and stinks of a thousand chemical and factory processes

caught his lungs. Stars there were none, nor moon. The city

howled and shook, screamed and wailed, wolf-like, machine-like.

so that he was a mite in the heart of a vastness of spinning

wheels, whining bearings and flaming mechanical wrath. He

clutched his ears, praying to awake. Stumbled, shielding his eyes

against the fiery glows projected against the sulphurous sky. He

fell, fingers scraping the filthy road. He wept, consciousness going.

Moments later two men stood over him. “Looks like a medical case,” one said. “Stress illness.”

“Yes. Bet he missed up on his sedatives.”

Expert, two of an unobtrusive medical corps, they picked him up and put him in a nearby vehicle.

“Waving his arms like a loony,” the first man said. “Funny how it takes them. And on a night like this too ! ”

He started the motor, and his companion nodded. He had seen many cases of untreated stress illness, and was accustomed to the sufferers foolish panics. “Peaceful enough for a saint,” he agreed.

He looked up through the open vehicle roof. The moon hung

clear and lovely in a sky barely marked by cloud. Stars shone and

soon the city would sleep. It was a nice city, he thought. Peaceful,

tranquil, pleasant — yes, no man could want a better.

Bill slept little and went out early. At the first corner he almost collided with a man who was walking briskly, smiling to himself.

“Chris! ”

Chris Berry smiled. “Thought I’d come along, and maybe look in to help you on that series, if you haven’t finished it.”

“You’re better?” Bill asked.

“Fine. I’m cured ! No more nightmares. Oh, but I had a bad one last night.” A frown came; vanished. “They took me in for a psycho, I gather, and stepped me up one in the sedative series, but it was worth it.” He grinned, filling his lungs. “Makes me glad to be alive, a spring morning like this ! ”

He walked at Bill’s side. “Guess I was getting into the habit of worrying,” he confided. “That special series you were doing for the Computer — nothing to it, really, you know.”

Silent, Bill walked on. That morning an official message had come from the medical centre, signed by Young. Mark was to go for a check-up. It was worrying, though things had turned out well enough after past checks. Bill had to admit.

“A morning like this reminds me of what Major Kenigan is fond of saying,” Berry stated chattily. He waved a hand. “Think of it. Bill ! Thousands of cities, all beautiful as this ! Clean, warm. happy . . . Mankind’s summer, Kenigan calls it. A favourite expression of his.” He patted Bill’s shoulder. “Why look glum?”

“Worried over my boy.”

Berry seemed not to have heard. “Swell how it’s all arranged. It’s the Computer, you know — works out everything for the best. And sees it’s done. Bet we’d never have a nice city like this without it.”

Bill’s step faltered. “Everything for the best — ”

“Sure,” Berry declared loudly. “For the happiness of mankind, and all that, you know.”

They walked on through the sunlit streets. At the Computer Block, Bill finished the series and the figures, graphs and dots disappeared into the equipment. The squiggled history of five hundred thousand souls, he thought.

When he got home he found Mark sitting on the balcony smiling. Judy came out, her face radiant.

“They say he’s all right,” she said to his questioning brows. “We’re to see he takes his sedative.”

He looked at Mark, who grinned.

“What’s that thing they put over a fellow’s head before they put him to sleep, dad? They say the Computer invented it.”

“I don’t! know. We must ask Dr. Young some day.”

Bill looked at the phial in Judy’s hand. Number four. The previous lot had been number three. They had stepped Mark up in the sedative series.

“Glad I shan’t have any more nightmares,” Mark said.

Bill remembered the last time he himself had been stepped up one in the sedative series. His was number six, and yellow. He had studied the first yellow pill with spiritual hate, said “Damn ! ” and swallowed it. If one forgot, by accident or wilfully, there was the nightmare — the rapid-acting capsule — the hangover the capsule left . . .

He went for a walk, arriving at a favourite spot just as the moon rose. The pale light danced on the waves which rolled placidly over the silvery sands. About him breathed the sweetness of the spring evening. Behind was a faint murmur from the city, scarcely as loud as the sea upon the shingle.

For a moment he felt content. He smiled to himself, trying to recall words he had read somewhere. Part of a poem, though he was usually too busy to give time to things outside Computer work. But tranquil words, fit for such a moonlight night — There is peace in dreaming.

He stretched, rising from the seat. It would soon be time to go home. A single gull was flying low over the water. He watched it go, and stretched again.

Once before, day dreaming there, he had forgotten his sedative. Time had passed. His illusionary fears had returned ... the gulls and sea had vanished. A complex mechanical city had drifted like a nightmare into his mind, screaming, vibrating, howling with plant and machinery. So complex and compact no man could live long in it and keep his sanity. He wondered why the illusion was always the same. He had suffered it, on and off, since childhood — since the first remembering.

He sighed, gazed for the last time at the curling-sea, and turned back into the city.

There is peace in dreaming.

Morning came. He watched Judy pour coffee. “Nice to know Mark won’t have those nightmares,” she said.

He nodded, his face showing nothing. He had slept little, instead lying with eyes open in the night. He could only agree, while in his mind was a conflicting bedlam of possibility and terror. For the twentieth time since rising his gaze passed out upon the scene below.

The sun was up. A few patches of light cloud suggested showers later in the day. An idyllic morning, for spring. Only faintly did the hum of the awakened city come to them. Opposite, a couple stood on their balcony. Laughter drifted across. Above the clouds the sky was the watery blue of spring, fresh and clean as the air breathing in through the opened glass door.

“I’m glad Chris is better,” Judy said. Her eyes were content.

Bill rose quickly, awkwardly, afraid that his emotions would stand revealed upon his face. She glanced up.

“You look tired, dear —

“Been rather busy.” He sighed to punctuate the lie. “Nothing to worry about.”

He turned to hide his face, staring through the open door, hating the city — hating its sunshine, its gentleness, its quiet content- ment. Damnable city, he thought. Most damned inferno of stinks and machines !

“I’ll get your raincoat,” Judy said. “Looks showery — but sunny, too. A nice day.”

Nice, he thought. Like hell it’s nice!

He kissed her, leaving, eyes averted. At street level he knew that he was going to follow the idea which had played around his mind since the night before. See Renton. Renton knew of Emanuel Zeker; knew of the break in history. Knew, therefore, other things— things yet unknown to most people. A person wanting to know about those things should thus see Renton. It needed no high-level logic to decide that.

He walked, sometimes doubting, sometimes accusing himself of childish fancifulness. Leave well alone. Yet leaving well alone could be the coward’s way out. In it would be no peace of mind for him.

He breathed deeply. The air smelled good. He let his gaze wander over the sunlit streets, creamy buildings and cloud-dotted sky. Then he screwed shut his eyes momentarily, lowered his gaze and strode on. Though ten armed secretaries and ten barred doors lay between himself and Commander Renton, he would see him !

When at last he faced Renton the Commander studied his finger-tips, his elbows on his desk, as he listened. Finally his eyes rose. “Is that all, Ashton?”

Bill let his physical tension relax. His fingers were numbed from pressure on the chair arm. “Almost all ! How did it begin ! Why is it permitted? ”

A hand halted him. “You assume the truth of your guess is admitted.”

“Isn’t it? And is it guessing?”

Renton doodled on his pad. “Let us put it another way. Suppose that most of the things you infer are correct. If men have to work in hell because that’s the way things have turned out, do they lose from believing it’s near heaven? ”

“But there could be other ways!” Bill interrupted. “Radical changes in industrial technique, replanning — ”

“Could there? We have a Computer whose partial responsibility is to look into things — and I have no doubt it has done so accurately and well. No man living or dead could improve any of its techniques.” He paused. “The processes in our industries are the best, conditions on this planet now being as they are. There is no ore for the digging, no oil, no natural resources of any mineral. Energy we have — 20th century science provided that. But energy alone cannot feed humanity. Fertilisers are manufactured with vast plant and incalculable energy from other intractible elements. A hundred-thousand kilowatts are dissipated in nuturing a day’s food for one man. Metals have to be made — re-created from rust and the sea. We have nothing but the dust and leavings of our spendthrift ancestors — ash from which to build a city — ”

He sank back in his chair, much of the fire going from his voice. Bill drew in his cheeks, his breathing momentarily stilled in the silent room.

“So it’s true,” he said.

Renton rose, not answering. “Time you were going, Ashton.”

Bill got up, leaning with palms spread on the desk, staring at him. “Is that the way it’s to be? Is earth to be a madhouse, drugged to quiescence? Is it to be drug after drug, always stronger. Hypnosis after hypnosis, always more deep? Babies cry. Kids wake screaming. Heaven alone knows what’s in the pills you give the old ! ”

“There are only twenty-five formulas,” Renton said thinly. “At present after those comes — death. The Computer is working on a twenty-sixth. There are difficulties — acquired immunity — ”

Bill scarcely heard. “Bedlam! ” he said. “A drugged madhouse ! Only the Computer knows!” He struck the desk. “Where does it end?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

Bill’s hand went into his pocket. It emerged with the phial. “Number six,” he said. “I suppose the need for changes speeds as we age!” He dropped it to the floor and ground it and the contents to yellow powder. “That’s where it ends for me ! Maybe there are some with guts enough to live in the world as it is, not as they dream it is! If so, then they’ll fight to change it! If men don’t know, how can they fight?”

He only halted when his hand was on the door. “I’ll find men with guts enough ! ”

“ There are such men, Ashton.”

The words sank in. “You mean — ?”

“Yes. Ten of us now — eleven, with you. Remember my words? I asked you if that was all. I was hoping it was not. But that denial could not come from me.” His finger indicated the remnants on the floor.

Bill put his back to the door. The room momentarily seemed to sway. “What shall you do?” His voice was a whisper.

“We’re planning. When I said the Computer’s industrial processes couldn’t be improved I wasn’t lying. But there are other planets — one other planet, in particular, and not so many million miles away.”

Bill felt relief, elation; anxiety, deep and biting. “How long?”

“Perhaps five years.”

“My son could come?”

“Perhaps.”

“My wife?”

Renton nodded slowly. “That’s up to her.” A bleak smile crossed his face. “The other road would have been easier for you, Ashton. You’d have been psychoed, drugged, hypnotised, drugged again. Likely enough you’d have been happy for another ten years. This can be a nice city.”

The tone of the last words made it clear and final. Commander Renton hated the city with all his being. Hated it for its insidious deception — for being a counterfeit, a lie. No oath could express that more clearly.

Bill opened the door. “I feel like that too. Commander,” he said.

A clear, inner calm had come. But he knew it would not last. This moment was the easiest part. There would be other moments, with no sedative to reawaken comforting images from drugged layers of unconscious memory, or to kill the impact of reality.

It was late when he reached home and Judy was drawing the curtains. “Pity to close them a night like this,” she said regretfully, “but I don’t want Mark to feel the chill.”

He watched her. The worst part was beginning. The draperies only shut out some of the flickering red of the furnaces transmuting the stones of the world into elements in which plants could grow. But steel doors could not have shut out the tearing rumble that shook the air, or quietened the maw of the screaming city. It helped to know that he was not alone — there were eleven others. But he prayed that the five years would prove enough.

Deep in the heart of the throbbing city a new-born baby howled.

Dr. Young slid a needle into its arm, put away his instruments, and

gave the mother a phial marked “Sedative Number One, For The

New-Born.”

Odd how they always cried like that, he thought as he left.

They screamed and shook their tiny fists as if to fight off some

nightmare bedlam of noise and terror. He frowned, pensive, and

buttoned his coat. The action made him aware of an unaccustomed

object in one pocket. Of course, the book, he thought. The old

volume the previous patient had unaccountably pushed into his

hand. He looked for the author’s name. Dr. Emanuel Zeker.

An unusual name, he decided. Possibly the book would prove interesting after all . . .

Francis G. Rayer.