Some odd word combinations have been left below exactly as printed, with only minor spelling corrections made.

Mr. Rayer has evolved many exciting story fragments concerning the Magnis Mensas from his original novel Tomorrow Sometimes Comes, not the least being “Deus Ex Machina ” and “The Peacemaker ” published in our earlier issues. In this new story the all-powerful thinking machine, designed to serve Man, is apparently losing its efficiency — its decisions go against the betterment of Mankind.

Illustrated by HUNTER

Forty-five levels high, vast and complex beyond the comprehension of Man , the Magnis Mensas stood in the heart of the teeming city . . .

The faintly humming lift ceased its upward motion and Jak Hemmerton stepped out into the corridor. Lean, tall, his step light and

quick, he strode with purpose. The building housing Rocket Enterprises was large, but he knew it like the lines of his palm. He had been

a boy when Rocket Enterprises opened ; had moved with the old stagers

when new offices, larger and more central, were occupied, ten years

before.

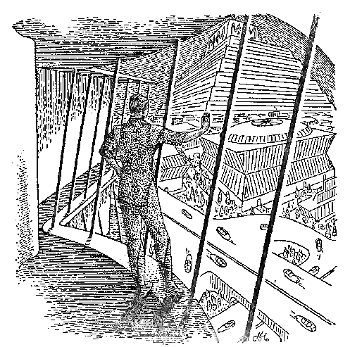

A transparent sound-proof door swung open and shut at his passage, and he turned along a corridor that was glass-walled, giving a clear view to the street below. Momentarily he halted, his gaze passing away over the rooftops to a gaunt, squat block like a man-made hill beyond. Only distance concealed its height and size, and hid the countless rows of windows. Huge in a city of large buildings, the vast pile housing the Magnis Mensas overshadowed and overtopped all other constructions. Jak’s lips compressed and a wordless exclamation passed his clenched teeth. Then he strode on, feet ringing on the floor, sandy brows drawn down, wide forehead crinkled in thought.

Bert Wingfield’s office was open and Bert sat behind his desk. At

forty, he had a mild appearance that was deceptive.

Jak halted inside the swing door. “We’ve got five years !” he

stated.

Bert looked up and sat back. His finger pressed a button halting

the desk recorder. Jak caught the action.

“ Keeping it off the record doesn’t give us more time !”

Bert Wingfield used a word no autotyper would have followed. “ Five years. Fifty might be too few ! We can’t design hulls until we know how big our engines will be. We can’t calculate engine size or weight until we know the characteristics of alloys we haven’t yet invented.” Features and voice were expressive. “ Did you tell the Magnis Mensas that ?”

“ Of course — though it already knows.”

“ And yet persists in giving us five years in which to reach space !”

“ Presumably it’s right, it always is,” Jak pointed out.

They were silent. Not for a hundred years had anyone contradicted

the Magnis Mensas without finding himself wrong. By its very nature

the Magnis Mensas was inevitably right, all-knowing, infinitely wise.

“ Can’t conditions be improved to give us more time ?” Bert asked

more quietly.

“ Apparently not. If men would play with atomics and worse it

was inevitable the reckoning come some day. Scientists pretended

Earth was a rubbish-dump of infinite size, knowing it wasn’t.”

“ Exactly.” The other touched a button on the intercom panel.

“ Have a ’copter on the roof.”

“ At once, sir ?”

“ Yes.” He released the button and stood up. “ Coming across,

Jak ?”

There was a spark in his eyes. Jak nodded. “ You’re going to

argue it out with the Magnis Mensas ?”

“ Going to try !”

They rode the lift to the flat roof, where Rocket Enterprises was painted large for any craft to see. With twirling blades ’copters swung back and forth across the city. Higher — much higher — was a silvery sheen like looking at a bubble from inside. Outside that bubble was — the refuse heap. Jak grimaced as he thought of the phrase. Once upon a time a refuse heap had been a small affair that bothered no one very much. Then the seas of the world and the good, clean air under the heavens had become the place of disposal. But disposal by dilution reached a point when contamination of the diluting medium passed safety limits. Now, cities were pure spots on the universal rubbish heap. A reversal of roles bound to come, Jak thought. Inside the bubble, water and air were pure. Outside, a man might live about four days without protective garb, or a month with.

They rose below whirling blades and Bert Wingfield set course for the grey, gaunt building away across the city. Many people moved below, dots upon the roads. Ant-like, people swarmed everywhere, busy with the doings of their own lives. Jak pitied them. Five years. So far, few knew the time was so short.

They landed in the ’copter park East of the huge block. Diffused early sunlight illuminated the forty-five levels above, a cliff-like expanse that gave no hint of the scores of levels below ground. They walked to one of the entrances. Jak felt awe. He always did. Here was stored the whole knowledge of Mankind, integrated completely. Built by men, the Magnis Mensas transcended men. So huge and complex had it become that a full knowledge of its circuit and working was possessed only by itself. No group of experts could have comprehended it as a whole — the span of a man’s life was too short, the power of human brain too small, to understand such complexity.

An attendant with “ M.M.” in gold on his green tunic showed them to a vacant cubicle. The door closed. Two chairs stood before a desk built in. On every side electronic eyes scanned them from the walls. Jak knew that deep in the basement electrical indices were flashing through the vast matrix of memory units.

“ You are known,” the Magnis Mensas said. “ Please sit down.” They sat, facing the reproducer grille. Bert Wingfield licked his lips. “ I wish to ask some questions.”

“ So I deduce, since you have entered a question cubicle.”

Bert caught Jak’s eye and Jak grimaced. It was always like this.

A man might talk with the Magnis Mensas all day and find the great

calculator one step ahead every time.

“ It is about the time limit set for the development of space flight.” The silvery blue discs faced them unmoving. “ So I assumed, since you have come in the company of Jak Hammerton, Number Y.781663, with whom I recently discussed the matter.”

Jak wished there were some personality in the voice. But there

never was. Its even tones could become unnerving. He leaned forward.

“ Cannot the period be extended ?”

“ It cannot.”

“ But it is so short — there is so much to be done !”

The Magnis Mensas was momentarily silent. “ You have asked no question,” it observed at last, “ but I would note both your statements are correct. The time limit is not imposed by me, but by external circumstances. It is not my task to formulate laws, but to evaluate data and present logical conclusions. I work wholly for the eventual good of Mankind. After five years life on this planet will not be generally tenable to your species.”

“ Can’t something be done ?” Bert Wingfield put in. “ Can some new method of decontamination be devised — ?”

“ There are no new methods,” the Magnis Mensas stated factually. “ All science is known to me. Every feasible industrial process is being used, or stands ready in plan awaiting employment. Conditions on this planet cannot be improved.”

Jak swore suddenly. “ I am not satisfied that is so !”

“ Your dissatisfaction arises from emotion, not from a logical consideration of known facts — ”

“ To hell with facts when it comes to quitting Earth !”

There was a pause. “ The terms of your observation are not understood,” the Magnis Mensas said at last.

They were silent. Jak met Bert’s eye and Bert shrugged. “ If it

says there’s only five years, then that’s that,” he said flatly.

“ But damn it — five years !”

There was silence, then the grille awoke again. “ Your use of unconstructive phrases shows emotional and confused thinking, Number

Y.781663. It is a characteristic already noted in your index of activity

patterns — ”

Jak flushed and got up abruptly. His tongue was silent because

sarcasm would be wasted.

“ Kindly do not slam the door as you go out,” the Magnis Mensas

said. “ It is a useless action based on emotional responses—”

The bang of the panels behind him cut off the words. Jak stood in

the corridor. It didn’t help to know that the calculator was always so

infernally right !

The busy day’s activity inside the building was commencing. Many

people passed, entering cubicles on that level or ascending to those on

the floors above. Not for the city alone did the Magnis Mensas exist,

but for the planet. Men came tired from long travel; a group passed,

speaking a strange tongue and with a guide whose bearing was of long

authority.

Jak took a ’copter back to his private flat. Affairs at Rocket Enterprises must wait. His wife Jean was in. If she felt surprise at the hour of his return she did not betray it.

“ Ever seen an ant at the foot of a cliff, Jean ?” he asked laconically.

Her long golden curls bobbed as she shook her head. “ No ?”

“ Then you’re seeing one now.”

He went through into his study. Space under the bubble was limited and it was small, though comfortable enough when he brought back work to ponder on. Now, the papers, diagrams and figures seemed mere mocking litter. Five years to reach space. An ant at the foot of a precipice . . .

Jean opened the door and came in. That in itself was unusual. Jak knew she understood he needed silence to work. Sitting on the edge of his desk, chin on chest, he raised his brooding eyes questioningly.

“ Thought you’d like to know Brayle and Avery are going ahead,”

she said.

A shock ran through him. “ I hadn’t heard !”

“ It was on the newscast just before you came in.”

“ But it’s impossible !”

“ It’s going to happen.”

There was a puzzled note in her voice and a question in her clear,

direct gaze. Jak wondered how much she understood or guessed. She

had a way of thinking out things for herself.

“ The Magnis Mensas sanctioned it ?” he asked.

“ Of course.”

He heaved himself off the edge of the desk. That Brayle and Avery

Industries should go ahead with their plan was completely at variance

with everything he had anticipated. It lent sudden decision to his

brooding idleness.

“ Think I’ll go over there !” he declared.

The head offices of Brayle and Avery Industries occupied a big block

away across in the business section of the city, and the ’copter touched

down on a roof already busy with craft. Jak found the lift and the

sumptuously furnished, magnificently designed floor upon which

Brayle and Avery worked. An outer office led to an inner, and that

to a further room where a vigilant young man asked for the appointment code number.

“ I have no appointment,” Jak said. “Tell them it’s Hemmerton

of Rockets !”

The other looked dubious but operated his desk intercom. The

replies from the directive reproducer were inaudible, but Jak thought

the person the other end the line had rather a lot to say, and the young

man’s expression was odd when he switched off.

“ Mr. Brayle says you may go in, Mr. Hemmerton,” he said.

He rose, opened a door, and Jak found himself in an office furnished

with overwhelming luxury. Brayle sat behind a desk of cream plastic,

no welcome on his wide face. He did not rise or extend a hand, but

leaned back so that the chair creaked under his bulk. He pyramided

the fingers of his powerful hands.

“ I didn’t know Rockets watched us so closely,” he observed.

Jak let it pass. “ I believe you’ve been given the go-ahead for the

new transmuting plant.”

“ We have— it’s common knowledge.”

Jak rose his brows. “ Would you say as much for the end result

of using the plant ?”

Brayle put his great hands on the desk edge and additional colour

showed on his face. “ We haven’t yet asked Rockets to run our business,

Hemmerton.”

The tone cut. Jak compressed his lips. “ I’ve come to discuss, not quarrel ! Rows of noughts look nice for yourself and your share- holders, but what use will money be when the Earth’s a stink-pot of atomic waste. Past folly and present essentials already contribute more than the rubbish-tip will take. Why add to what we’ve got out there?” He jerked a finger to indicate the silvery dome covering the city.

Brayle looked amused. “ The planet’s big enough to take it. The seas and winds of the world are big — ”

“ But not infinite ! The overall contamination level is already too high, but some things can still live out there, even if men can’t. You’ll build up pollution.”

“ We’re snug enough in here,” Brayle stated.

Jak saw it was going to be useless. “I’ll fight it every inch !”

The chair creaked as Brayle rose. He came round the desk and

put his face six inches from Jak’s. Of similar height, he was twice as

broad.

“ Men who fight Brayle and Avery don’t find it much fun, Hemmerton,” he said. “ What’s more, you’ll be fighting the Magnis Mensas as well. If we want to transmute — we transmute. If we want to make money — we make it. Money still talks, if you have enough. Money interests me and my shareholders. Your piffling scientic theories do not.” He leaned over and pressed a button on his desk. The door opened at the vigilant young man’s touch. “ Show Mr. Hemmerton out !” Brayle ordered.

Jak halted at the door and looked back momentarily. “ You’re fouling the pond you’ve got to live in!”

As he rode the lift to the roof he hoped his parting shot had hurt. There, he sat for a moment with his hands on the segment wheel of the ’copter. The clock on the dash stood at noon. With a start he remembered he had had an appointment for eleven. Too late now to go back to Rocket Enterprises to keep it. He wondered if the young man he had intended to meet had waited. On vidiphone the youngster’s face had been honest and intense. Jak recalled his name. Dave Reader. Reader had claimed to have something Rockets would like. Jak shrugged as he took the ’copter up. A major miracle seemed required and it was unlikely Reader would have had that to offer. Then his mind returned to Brayle’s words. Brayle had a go-ahead from the Magnis Mensas. That almost suggested there had been a slip up. The streets below seemed to swing up as Jak took the ’copter in a tight curve. It was, it seemed, time to call the Magnis Mensas to task !

He had to wait fully ten minutes before a cubicle became vacant. The door swished shut behind him and he sat down heavily.

“ You are recognised,” the Magnis Mensas said.

Jak eyed the screens pensively, arranging his thoughts. Doubt and

triumph conflicted in his mind.

“ Is it not correct that mankind’s position on this planet is growing

untenable because of the general pollution of air and sea by byproducts ?” he asked.

“ It is.”

“ And all additional pollution worsens conditions ?”

“ Obviously.”

Jak felt triumph. Brayle had obviously faked permission — the

Magnis Mensas would never allow further harmful by-products to be

poured into the atmosphere.

He leaned forward, gazing at the impersonal discs as if to discover some hint of the almost omnipotent intelligence behind. “ You are aware of the nature of the proposed Brayle and Avery transmuting plant ?”

There was a slight delay. “ Full data of it are filed in my indices.”

“ It can transmute base metals to metals more noble ?”

“ That is so.”

“ It would employ atomic processes and its harmful atomic by-

products would be considerable ?”

“ They would.”

Jak felt sure, now, that triumph was his. “ Then are you aware

that Brayle and Avery intend to use the plant ?”

“ I am.” The tone was absolutely without emotion, as always.

Jak leaned back. “ Then you will prevent it ?”

There was a moment’s silence. Then the grille awoke. “ I shall

not. I permitted its use. Therefore to prevent it would be illogical — ”

A shock ran through Jak. “ You permitted it ?”

“ Certainly,” the Magnis Mensas said.

“ But you agreed that it would be harmful !” Astonishment made

Jak’s voice shake.

“ I did. But your assumption that I would prevent its use for that

reason is based on incomplete data. I work wholly for the eventual

good of Mankind.”

“ But Brayle’s plant can’t be for anyone’s good !” Jak cried.

“ I have deduced that it will be so.”

Jak stared at the screens, tongue-tied.' “ I — I don’t understand,”

he breathed.

“ The knowledge at your disposal is insufficient. Deductions based

on insufficient knowledge can be incorrect.”

“ But — you gave us five years,” Jak pointed out.

“ That was correct. Since I intended to permit the use of the

Brayle and Avery plant, its effect was integrated with the other data.”

“ Which means we should have more than five years if the plant did not operate,” Jak grated.

There was no answer. From his knowledge of the Magnis Mensas Jak knew he had made a statement, and that its silence meant agreement. If he had made a wrong statement, it would have pointed out his error.

He left the cubicle and descended to the ’copter park. His head swam. It had appeared so certain, so sure. Yet the Magnis Mensas took a different view and must, by its design, inevitably be correct. It was baffling.

The park and roads dropped away below. Jak had set a course for

the Rocket Enterprises office building when the flash glowed abruptly

from earth to heaven a mile away outside the city dome. Bright even

in the noonday sun, it lit the city, then was gone. Adjacent, the

tenuous city dome rippled, the ripple spreading quickly nearer, overhead, and away. Then the sound came — a sharp explosion of great

volume, followed by echoes as from a thunder-filled sky. Faces turned

upwards and vehicles stopped. The ’copter shook slightly, floating

on under spinning blades. Jak knew of only one possible source of

an explosion of such magnitude. Face suddenly white, he set the

blades at a sharp angle and arrowed towards the building where he

had worked so long.

“ You’re right in thinking it sets us back,” Bert Wingfield said. “ Apart from the actual loss, there’s the uncertainty. Everything has to be checked all over again. We’ve got to look for flaws in design where we believe there are none. And if we fail — then the next rocket goes the way of the last !”

Strain was clear upon his face. For the previous hour phones and intercom units had been acting half a dozen at a time. Jak had arrived amid the chaos.

“ Many killed ?” he asked

“ All the maintenance crew. They hadn’t a chance and probably

never knew what hit them.”

“ You’ve no clue ?”

“ None yet,” Wingfield said, and his slight frame seemed to have

shrunk. “ There’s only a crater and scattered debris, and that doesn’t

tell one much.”

He sat down with the movement of a very tired man. Jak thought of the gleaming rocket that might have reached space. As Bert said, half a square mile of fragments told one little.

“ We’ll begin again,” he said. It was not the first time. Nor were Rocket Enterprises the only space-ship engineers to suffer such set- backs. Early trials had been deceptively easy — it was easy to shoot a hull full of electronic equipment into the stratosphere. But ships to carry people were different. Men were less tough than printed circuits sealed in plastic, and most inconveniently died through lots of awkward reasons . . . While a robot or radio-controlled ship could be set down on Mars, if anyone bothered, the moon was still too far for living men.

“ Oh yes, we’ll begin again,” Bert Wingfield said, and sighed. He fiddled with the mess on his desk, came across a pad, and turned it up the right way. “ Clean forgot — there was a Dave Reader here at eleven. You were to see him.”

“ Sorry.” Jak wondered if it mattered. “ He coming again ?”

“ Same hour tomorrow.”

“ I’ll see him.”

Dave Reader sat on the very edge of the chair and his youthful face

glowed with eager enthusiasm.

“ You believe it would work, Mr. Hemmerton ?”

Jak eyed the diagrams, the sheets of data, making no mean pile on his desk. Though Reader was a youngster, he certainly had something! He was alternatively confident and hesitant, but behind it all lay a keen brain. Jak met the boyish eyes, so bright and direct.

“ I believe it may,” he said.

“ Then you’ll give it a trial ?”

“ If my partners agree.”

Reader rose, impulsively leaned over the desk, and shook Jak’s hand

warmly. “ I hoped you would ! I’m sure it’ll be a success ?”

When he had left Jak sat with his chin on his chest and idly turned over the diagrams. Dave Reader had worked it all out on paper and had no money or equipment for tests. But the idea promised to make the next rocket design a trifle easier. So far, they had tried three methods of providing a breathable atmosphere for crew and passengers. Jak ticked them off mentally. One, cylinder-stored oxygen — compact, good for short journeys, but useless for long period operation. Two, plant tanks. They had seemed hopeful, but been too bulky. Three, chemical exchangers. Promising, but upset by both acceleration and the weightlessness of free space. Reader’s idea could be more compact, more efficient, more foolproof.

The more Jak pondered the scheme, the more he liked it. It would reduce weight — could deal effectively with vast amounts of contaminated air . . .

The last point stuck in his mind. Designed for rockets, it could have other uses. He began to make notes, scaling up capacities. What could be done for a rocket might also be done for a planet — if the scheme was efficient enough. And Reader’s idea alone looked as if it might be just that.

After rather more than two hours Jak felt confident that the plan could work. He wrote out a factual report, omitting nothing, and had just finished when Bert Wingfield came in. From the file under his arm Jak guessed he was taking data to be checked.

“You going to the Magnis Mensas ?”

Bert nodded. “ I’ve everything we know here.” He tapped the

thick folder. “ If it can’t deduce the cause of the blow-up, no one

can.”

Jak gave him the report. “ Have this filed in.”

“ I will.”

Alone, Jak wondered what the calculator would make of Reader’s

plan, enlarged a hundred fold. If it had trifling defects, they could be

ironed out. The Magnis Mensas, could not create, it could only work

from known data. In that respect alone was the human mind its

superior. A flash of genius could devise something new. The inventions of the Magnis Mensas were new in a different way— were always

new permutations of old data.

In the days that followed, the Rocket factories outside the city bubble membrane moved into their new, hastily arranged production schedule. Jak went out often. Outside the dome a first glance would suggest nothing wrong. But there was enough radioactivity in the air to do things to a man’s lungs, unless he wore a suit . . . Suited, his stay could be longer. There had been heavy rain, and the ground contamination was up. Jak was glad to reach the factory. Its dome, fragile as a child’s balloon, and supported by internal air pressure fractionally above that of the outside atmosphere, glistened from the downpour.

He spent an hour inside, and was satisfied that such preliminary work as was possible was gaining momentum. The possibilities of Reader’s idea were never far from his mind, and he retired to a private office and dialled a connection to the central information office of the Magnis Mensas. Time for its decision to have reached the records, he thought.

The girl listened to his request and went away. Moments passed,

then: “ I have the tape covering the Reader plant here, sir.”

“ Please play it.”

Jak sat back, gazed through the window on the plastic bubble.

Might come a day when such protection was no longer required . . .

The report began with index data in impersonal tones. “ As a

result of analysis, it is apparent that the plant would not in practice

prove operable and its construction, even in experimental form, cannot

therefore be recommended — ”

Almost overbalancing, Jak snapped from his position of repose.

“ Play that again !”

“ Yes, sir.”

He had not heard wrongly ... his astonishment grew as he listened

to the detailed explanation following, and to the long statement’s

conclusion.

“ It is therefore recommended the plant be abandoned, except insofar as scaled down units might prove of service.”

He snapped the line off and drew in his lips. It was impossible !

If the plant would work in small scale, it would work in large ! Yet

the conclusion of the Magnis Mensas meant, in brief, that Reader’s

idea would do for ships, but not to combat atmospheric pollution on

a planetary scale. “ Damn” Jak said aloud. It did not fit.

He got his protective suit, went out, and skimmed back to the city bubble. Bert would not expect him back, he thought. But this could not wait. He left the ’copter in the decontamination park, passed the membrane lock, threw off his suit, and took a ’copter back to a bumpy landing at the Rocket roof-drome.

The lift put him out on their office level. Scowling, he strode along the corridor, along the transparent-walled balcony — and halted.

A man his own height but heavy of build had just come from the swing door of Bert Wingfield’s office. There was a glimpse of a big, wide face, then the man was gone with heavy step on along the corridor. Jak felt his scalp tickle and blood pound momentarily to his cheeks. He had told Bert he would not he back . . .

Wingfield was sitting on the corner of his desk when Jak entered.

He started visibly.

“ Didn’t expect you this soon — ”

“ So I’ve noticed !” Cut, clipped, the words stung visibly.

Bert Wingfield slid from the desk. “Why so ? What’s biting you?”

“ Since when has Brayle had business in these offices ?”

The other’s mild face was lined. “ He wanted to talk business.

Nothing important — ”

“ Important enough to take place when I shouldn’t be here !” Jak

snapped.

A flush spread over Wingfield’s face. “ You’re making a mistake !”

“ Perhaps I have — too long.” Jak felt cold, as a man betrayed. “ Just now I’m asking myself several questions. Seeing Brayle leave your office gives me new ideas.” He leaned forward, hand on the desk. “ Just how did you fake Reader’s specification to get it rejected by the Magnis Mensas ?”

There was silence. Jak guessed at possibilities. He was sure Reader’s idea would have worked — on planetary dimensions. It was thus big enough for Brayle and Avery Industrials to cash in on and corner for themselves. Perhaps Brayle wanted to break Rockets. Perhaps Wingfield liked the look of some of those noughts Brayle had mentioned . . .

“ I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Wingfield said.

“ Like hell you don’t !” Jak’s lips closed like a steel trap on each

word. “ It’s seven years since I brought you into Rockets. We got

on all right before — we can get on all right again ! Now, get out !”

A visible shock ran through Bert Wingfield’s body. “ Get out of

Rockets ?” His voice shook.

“ That’s what I said. Maybe Brayle will give you a job !”

Wingfield licked his lips. “Something’s bitten you, Jak. Remember what the Magnis Mensas said. You’re highly strung — ”

“ To hell with the Magnis Mensas!”

“ At least let me explain — ”

“ Any fool can explain anything — but that doesn’t make me fool

enough to listen !”

Silence grew. Abruptly Wingfield turned on a heel and left the

office. The door swung shut at his back.

Jak watched its vibrations cease. Tall, he had become suddenly

stooped. His sandy brows had come so low they hid his eyes and his

face had aged.

He sat at the desk slowly, put his elbows on its top and his palms

on his eyes. Damnation, he thought. Bert Wingfield. Bert !

In the months that followed, Jak worked alone. To himself he admitted that Bert’s absence slowed progress. Bert and he had formed a team and accomplished together things neither could have done alone. The small Reader plant for rockets was passed and went into production. Brayle and Avery’s transmuting plant began to pour a column of grey smoke into the outer atmosphere. Jak calculated the degree of contamination it caused and took the figures to the Magnis Mensas. The calculator agreed with them, said the information had already been available to it, but maintained that the work could continue. Jak wondered. The next evening there was a sudden step behind him in the dark patch between street and lobby in the block where he lived. Some unnamed sense brought him round half a second before normal, and lifted his hand in a reaction barely quick enough to grip a descending wrist. The man’s hand was gloved, the dagger long, slender — and silent.

Jak struck with his left fist and missed. The other was powerful, agile and twisted free with a strength that made Jak’s fingers creak. The blade rose from near the floor. Jak jumped back and kicked. His toe met the other’s stomach, bringing a grunt and a fifth-second of paralysis. Jak’s hands locked on the knife wrist and he heaved. Something snapped like a stick and the knife fell. Grabbing for it, he lost his hold and the man was gone.

In the lobby, Jak studied the knife. It was without markings, a single piece of steel. The blade was like a razor, the haft slightly rough — hand made. He put it inside his coat.

As he went up to his flat he recalled a phrase Brayle had used. Brayle and Avery did not like people who meddled . . .

The flat was silent and empty. The words of greeting died on his lips. Jean should have been there — was always there. He swore, thinking of Brayle, then knew it was not that simple. His life had been attempted in the lobby. Brayle would not have risked a kidnapping as well, when the threat it constituted would be pointless if the knife had done its work. If not Brayle, who ?

He enquired of the building clerk below. Jean had gone out two

hours before, in reply to a message. The sender was not known.

Jak paced the empty rooms, biting his lips. Two hours before.

That cleared Brayle. With Jean kidnapped as a threat, there would

have been no murder attempt.

She did not return. He had not expected it. Free, she would have rung, explaining. He wondered why she had not left a note. There seemed two possibilities — she had expected to be back before he arrived home, or had lacked time.

The night and day following were agony. Every enquiry he made

lead nowhere. He wished Bert had still been at Rockets. Bert would

have understood his feelings, and might have helped. He almost rang

the flat where Bert had always lived, but memory of Brayle slipping

from the office halted him. Once betrayed, twice shy.

At last frustration, distress and helplessness took him to the Magnis Mensas. Here, at last, might be information, without which everything was mere guesswork.

“ You are recognised,” the machine said. “ Please sit down.”

Jak sat. The air of the cubicle hummed faintly. Within the huge

building there was never complete silence, but a murmuring, breathing

background of activity.

“ I wish to report the disappearance of my wife,” he said.

He gave details as he knew them.

“ Information noted.” The voice was impersonal as always. “ That

is all ?”

“ No.” Jak leaned forward, staring at the screens. “ I wish to

find her.”

“ A logical desire.”

“ I fear she may be in danger !”

There was silence, then: “To your implied question — it is feasible

to assume so. Her absence is to you unexplained and unexpected. In

view of the socio-domestic relationship between her and yourself, you

have assumed she would not be absent without explanation ?”

“ I have,” Jak said. A shock had run through him. The words hinted at a possibility never occurring to him: that Jean was absent freely ! He hesitated. “ Refer to her activity and psycho patterns and tell me whether you consider she would go freely and without explanation.”

He waited with mounting tension. At last the grille awoke. “ All data relating to Jean Hemmerton, Y.B/781663, indicate that it is not logical to assume that she would absent herself from you of her own will and without explanation. Her socio-domestic relationship was satisfactory.”

“ Then she was taken by force or trickery ?”

“ It is logical to assume so.”

“ Would a person kidnap her simultaneously with attempting my

life ?”

Seconds passed. “ Not if her removal was to force you to undertake

activities for which you have no inclination; or, secondly, to prevent

you engaging in activities which her kidnapper personally considers

undesirable.”

That cleared Brayle and Avery, Jak thought. He seemed to be up

against a blank wall. He rose, hesitating.

“ You don’t know where she is, I suppose ?”

There was no reply. No reply was agreement, he thought. With a

hand on the door, he hesitated. His words were a statement, backed

up by a supposition that it was correct. It was not always easy to remember that the Magnis Mensas was not human. An odd feeling

came; he stood with his back to the door and knew he had paled.

“ Do you know where she is ?”

“ I do,” the machine said.

A shock ran through his nerves. “ Who took her ?”

Seconds, then: “ I did.”

He bit his lips so that it hurt, and gripped the chair back. “ You !

She — she is alive ?”

There was a delay. He knew complex circuits were channelling

information away, waiting for the response. The reply would be

based on immediate information . . .

“ She is alive, well, but resenting captivity,” the Magnis Mensas

observed at last.

Jak’s nerves twanged. There was relief, dismay. “ But — you !

Why ?”

No reply came. He strode round the seat, shook a fist at the screens.

“ I demand that you answer ! You are built to serve mankind !”

“ Your second supposition is correct, your first demand unreasonable. The two conflict. If I reply, I shall not be best serving mankind. Therefore it would be illogical that I answer.”

Jak put a fist before the largest screen, shaking it. “ In the name of

sanity, what do you mean ?”

A low murmur as of reproof issued from the grille. “ Your activity

patterns are reaching a level where emotional responses are submerging

logic — ”

“ To hell with logic! ” Jak snorted.

“ Your statement is not clear.”

Jak drew a deep breath. “Tell me where my wife is !”

Silence, then: “ For the reasons already given, it would be illogical

of me to do so.”

“ I demand it.”

Silence, unbroken. Jak knew that he had reached the final point in his discussion. If a madman asked how to make a tommy-gun, the Magnis Mensas would not reply: it would be illogical, harmful to humanity, to do so.

Shaking, he stood at the door. “ You refuse to answer my question?”

“ Regrettably I must.”

His shock was so great that he did not even slam the door. Outside,

he stood in the corridor like a blind man. Then he turned his steps

towards the ’copter and home.

Jak slept little. The next day he returned to the great building and tried to make the Magnis Mensas disclose Jean’s whereabouts. The reply was inevitable: “ It would be illogical to do so since you might try to secure her freedom.”

He strove to concentrate on his work, but more than ever admitted that he missed Bert Wingfield’s co-operation. Bert was a born rocket man . . . Some odd sense told Bert things which other rocket men needed to discover by calculation or trial and error, costly and time- consuming.

Reader’s apparatus functioned perfectly at space-ship size. The youngster was often seen in the Rocket Enterprises building. Brayle and Avery’s transmuting plant poured radioactive wastes into the atmosphere outside the city bubble. The value of their stock rose sharply.

Unexpectedly, Rocket Enterprises received a directive urging a fourfold step up in experiments and construction. It was backed by an official sanction for labour and materials. The form bore an imprint showing the idea had originated in the Magnis Mensas. The labour directive was similarly stamped and took no less than 7,000 men off atmosphere work, making them available to Rockets. Jak swore at sight of it and dialled one of the few personal lines to the Magnis Mensas.

“ You intend to leave Earth to stew in its own filth ?” he snapped.

The reply was emotionless. “ From a consideration of all existing

data it has proved desirable to increase your speed of working — ”

“ But why send us men from atmosphere plant ?”

“ They are most skilled and therefore most suitable employees.”

“ But atmosphere work is vital !”

“ It is,” the Magnis Mensas agreed. “Yet it is nevertheless secondary. I would remind you that I have computed that this planet will

inevitably become untenable to human life. The atmosphere purifying

plants only delay that moment.”

The line went dead and Jak switched off with fury. The great purifying plants would only delay the moment ! Was not delay, and yet more delay, of that moment the thing most needed ? Meanwhile, Brayle and Avery were hastening its coming. Worse, Reader’s equipment was only built in ship size, instead of with a capacity which might have had planetary utility.

It was baffling. He strode up and down his office, kicked a chair over, swore, wished Bert were with him, and then halted. If one thing stuck out a mile, it was that Brayle and Avery were growing rich. Brayle and Avery were big. Brayle and Avery sometimes worked things their way. Might, for example, have messed with the great computer so that the answers it gave, in some directions, were the answers they required . . .?

Jak left his office and spent an hour studying city plans in the library archives. He decided that secret access to the inner parts of the Magnis Mensas might not be difficult. To date, everyone was highly satisfied with the computer. No attempt at damaging it had ever arisen.

He followed the plans as he supposed Brayle might have done. Water from a coolant heat-exchanger in the computer basement issued into a river outside the city. Suited, he found the opening. His powerful torch showed a tunnel ten feet in diameter and barely one third full of water. An hour later he emerged in a large square catchpit shoulder deep with hot water. An inspection ladder on one side gave egress from it.

The first door he opened revealed a lobby holding spare uniforms marked “ M.M.” and he donned one, hiding his suit. A throbbing murmur filled the air. For the first time the sheer impossibility of discovering anything in so vast a building arose in his mind.

Ahead was an open door marked Bay 712. Through it he could see a great chamber in which information matrices stood in rows from floor to ceiling. Cables beyond number vanished into upper levels and the equipment chattered and whirred with spasmodic activity. The chamber seemed otherwise empty, and he stepped through.

“ What is your code number and purpose ?” a voice murmured.

Halting, shocked, Jak saw he had interrupted a light beam that

crossed the doorway. Above the door was a grille— from it had come

the familiar intonation ...

“ I — ” He strove to improvise quickly. “ I was sent to check a

fault—”

He counted five heartbeats. Then a gong rang. “ No fault has been

reported in this bay,” the Magnis Mensas said. “ Furthermore, your

reply is not satisfactory — ”

He was running even as the words ceased. From the opposite direction two men came hastening. Behind him others appeared. Within moments he was held.

“ Place him in a question cubicle,” the Magnis Mensas said.

Frog-marched and pushed from behind, Jak found himself in a

narrow cell. A grille in its roof awoke to life.

“ Your unauthorised presence requires explanation. Before you

begin, I would note that your act may have serious consequences for

yourself.”

Jak wondered whether he should lie, and thought desperately that

perhaps he should not. Instead, he must trust to the machine’s

complete logic and fairness.

“ I thought someone might have interfered with your units, and

wanted to see if a man could get in,” he began . . .”

It was three hours later when Jak emerged on to the street at the

rear of the Magnis Mensas building. The pair who propelled him

from the door were friendly but severe.

“ If this happens again you can expect a year in jail,” one said.

The other nodded. “ Bay 712 is a hotspot. It’s new, and the computer’s got data there none of the units upstairs ever touches.” His words remained in Jak’s mind. Rockets had money and contacts, and with both there were ways of finding things out . . . Within twelve hours he knew the man’s name, where he lived, and his recreation haunts. Within twenty-four hours Jak was paying for a drink for him in one of the saloons near the city-bubble rim.

“ You’re the man we threw out,” he said, and Jak laughed.

“ I didn’t want to do damage. I told the M.M. so, and it believed

me. Have another drink ?”

“ Can do,” the man said.

Another followed. They sat down and Jak motioned for more.

“ Wonderful machine you’ve got there,” he said in frank admiration.

The man drank again. “ Remarkable.”

Jak filled his glass. “ Wonderful how it works things out.”

The man nodded. “ Mos’ splendid machine.”

“ What’s that in Bay 712 ?”

The man looked round, focused his eyes with some difficulty on Jak, and put a finger on his chest. “Wonderful new data layout.” He drank. “ The ole M.M. thinks there to itself all day an’ night. All the indices clicking like mad all the time, even when the cubicles are shut for the night—”

In a full hour more Jak could get nothing further from him, and decided this was the extent of his knowledge. When Jak left the man’s head was pillowed on his arms and he did not look up, speak, or move.

The night air cleared Jak’s head. An idea which had slowly matured in his mind settled into concrete form. He must seek out Bert. Rockets needed him. He, Jak, needed him. There was no one else who would, or could, help find Jean. Jak turned his steps towards the engineers’ flats. He must apologise, climb down, listen to Bert’s explanation, if there was one . . .

He felt happier than he had done since Jean’s disappearance. With Bert by his side again, Rockets could make speedy progress. With Bert, he might find Jean.

The “ IN ” tab on Bert’s door was illuminated when he rang.

When Bert opened Jak grinned lopsidedly.

“ I’m sorry, Bert. I’ve come to apologise — to listen to you.”

Something in Bert’s face told him he had not called in vain.

An hour later they were back in the Rockets office. Jak felt a glow

of strong satisfaction.

“ Your absence has put us back six months, Bert ! We need you

here.”

“ We’ll catch up,” Bert said. “ First there’s a personal matter.”

He rang the appointments girl below; had to repeat his order: “ Yes,

I did say Brayle of Brayle and Avery. Tell him I’ve thought over

what he said when he was here last, and would like to see him.”

He sat back in his chair with satisfaction. “ That will fetch him,”

he declared.

Jak stared at him. “ But—” Words failed to come.

“ You’ll soon see,” Wingfield said. “Brayle will be here quick as

’copter can bring him. You go in the next room. Keep out of sight

but listen.”

Among the files in the adjoining office Jak wondered what was to

happen. Within fifteen minutes he heard Brayle admitted.

“ I hoped you’d give it more thought, Mr. Wingfield.” The tone

was jovial.

The sound of Bert’s chair being pushed back came. “ You still

want me to see that Jak Hemmerton — doesn’t cause you any more

trouble, as you put it ?”

“ I would not use such direct phrasing.” Brayle sounded almost

apologetic. “ An accident — a slip at the works, perhaps — ”

Three quick steps sounded, and a thud. Jak looked through the

door and saw Brayle sitting on the floor, nursing his jaw in astonish-

ment.

“ That’s the answer I’d like to have given you the first time you

called !” Bert said.

Brayle got up, face red and white in patches. “ I’ll have you jailed!”

Bert laughed. “ Get out !”

Jak stepped through the door. “ Like to guess what I’d say as a

witness, Brayle ?”

When they were alone Bert sat on the corner of the desk. “ I owed

him that. The next thing is Jean. You can’t work till she’s back.

This mess started in the Magnis Mensas, and I’ve a feeling that’s

where it’ll end.”

Jak was silent. True, he could not work without Jean safe home.

Without her, he was ineffectual as Rockets without Bert. Yet getting

her back looked like a straight fight with the Magnis Mensas. If so,

it must inevitably fail.

“ Let’s get moving,” Bert suggested.

Many people moved in the corridors leading to the thousands of

question cubicles of the Magnis Mensas. On the second level Jak

found a door with the “ Vacant ” sign illuminated, and they went in.

“ You are recognised,” the Magnis Mensas said. “ Please sit

down.”

They did. Jak listened to the low murmur filling the tiny room,

and wondered how best to frame his thoughts.

“ I am not satisfied of the way in which you have conducted a

number of affairs,” he stated.

The reply was immediate. “Dissatisfaction is based on personal

disappointment. It may be inevitable when external circumstances

postulate developments unfavourable to the individual.”

Jak leaned forward, staring at the grille as if to see through it to

what lay beyond. “ Yes. But there is no excuse for developments

unfavourable to all mankind !”

Silence, then: “ Your statement infers developments unfavourable

to all mankind have arisen.”

“ They have !” Jak declared. “ Brayle and Avery contaminate the

air with their new plant. That benefits individuals but harms mankind. Large-scale Reader purifiers have not been made. Now,

Rockets are using personnel who should be on atmosphere work.”

“ Your statements are correct.”

“ Then you agree that these things are not best for mankind ?”

Jak snapped.

“ I do not.” No overtone of modulation varied. “ Your suppositions are based on an insufficient understanding of humanity and insufficient data. They must accordingly be incomplete. They are also

incorrect.”

Jak felt his head whirl. Talking with the Magnis Mensas was never

fun. Arguing with it could be-; — hell.

“ Inform me how my observations are incorrect,” he ordered,

suddenly tired.

“ In several ways. Closure of the Brayle and Avery plant would

reduce pollution of the atmosphere. Planetary application of the

Reader system would similarly reduce pollution — ”

“ But in heaven’s name isn’t that what we want ?” Jak grated.

The droning voice ceased for only a moment. “ Ignoring the first

part of your remark, which is effectively without meaning in the text

in which you employ it, a reduction of pollution is not what I require.”

Jak felt as if kicked in the stomach. “ Not what you require ?”

“ No,” the Magnis Mensas stated. “Members of your species do

not leave their homes unless factors require. Such factors may be

found in the desire to explore, to escape inconvenience, or to discover

a manner or place of living they feel preferential. A race consists of

individuals and must therefore evidence the same characteristics.”

“ You mean we would never leave Earth unless driven out by

atmosphere pollution ?” Jak cried.

“ Not wholly. Only that your leaving would be vastly delayed.”

In the silence Jak reflected that was so. Only the atmosphere pollution had brought public support to such undertakings as Rockets. In

the creamy light he saw that Bert’s face was white.

“ Why is it necessary that humanity leave Earth ?” he demanded.

“ Because there is a time limit during which he must reach space.”

In the murmuring cubicle they stared at each other. This was a

development Jak had never expected. A time limit during which men

must reach space — and one not set by atmospheric pollution !

“ It is for the same reason that your wife, Number Y.B/781663, was

removed by me,” the Magnis Mensas observed.

Jak’s mind snapped back to Jean. Jean, who knew nothing of

rockets, atmosphere work . . .

“ Damn you for it,” he said.

If matrices in the machine gained any meaning from the phrase

they did not initiate any related reply. “ Her removal was necessary,”

the grille murmured, “ and was based on a careful study of your

activity characteristics, among which may be listed stubbornness, pride,

obstinacy in retaining incorrect opinions — ”

“ Quit the praise and come to facts !” Jak growled.

“ Very well. It is essential for the future of humanity that yourself

and Bert Wingfield work together. The captivity of your wife was

the only feasible conflict sufficiently strong and personal to you to

make you seek his help — ”

Jak felt as if caned. “ You mean- — it was to bring us together

again — ?”

“ Certainly, as I stated. Since I observe you together the need now

ceases, and I have already initiated her freedom.”

Jak put a shaking hand to his forehead. It was as the machine said.

No other personal conflict could have taken him back to Bert, or made

him swallow his words. His mind switched to a new matter.

“ I know you to have set up a new series of data in Bay 712 !” he

stated. “ I demand to know its content !”

“ The data are known to no human on this planet.”

“ I demand !” Jak wondered if this were mere obstinacy on his

part. “You cannot keep secret information in this way !”

There was a silence. “ I can, if I should deduce that to do so would

be beneficial to mankind,” the machine stated finally. “ And this is

so in the present instance. Nevertheless, it is apparent that you have

progressed in the knowledge of related factors, and will not be content

until the whole is known to you. Since your maximum ability to work

is essential, and can only be had by your contentment, I will inform

you.”

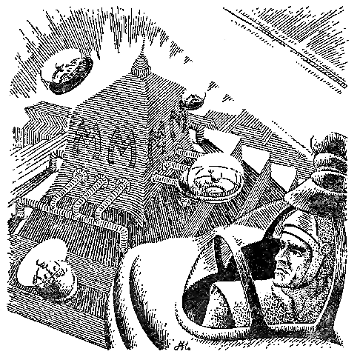

A long silence came. A screen before them lit up. “ I am transferring circuits,” the Magnis Mensas said. Blips showed on the screen,

moving, too tiny to have form. “ These signals are being received

from the direction of Castor Major. I first observed them among

supposed meteorite echoes. They are proceeding towards this planetary system at a speed approximately half that of light. The blips you

observe have been over two years in transit. From analysis of all

related data, I have deduced that they are spaceships. Their characteristics permit no other explanation.”

“ Alien ships, coming to this system — to Earth !” Bert Wingfield

breathed.

“ Exactly. Had mankind been informed when I first knew, panic

would almost certainly have resulted. Panic reduces efficiency. My

purpose is the sole eventual good of mankind.”

“ The atmospheric pollution is not important,” Jak cried suddenly

understanding. “ You even allowed it to be increased, to make us

build rockets faster !”

“ As you suppose. Mankind must be able to meet these newcomers

in space as equals.”

The Magnis Mensas was silent. Jak felt overwhelming admiration.

Rockets would see to it that mankind was in space when the alien ships

came ! How different that meeting would be to the terror of being

Earthbound while great ships circled overhead ! It would be a meeting

and parley between equals — not a fearful plea for terms . . . . !

He rose so abruptly he almost upset the seats. “ I want to see Jean !

And, Bert, there’s work to do — !”

They almost jammed in the door.

“ Vacate the cubicle singly,” the voice droned behind them. “ It

is illogical to — ”

The spring-loaded door banged, shutting off the words. Jean was

coming along the corridor, conducted by a guide.

“ There sure is work for Rockets, Jak.” Bert said.

They looked at each other, at the closed door marked “ Vacant,”

and turned for the nearest stairway. Certainly a tough way to get men

into space quick enough, Jak thought. But necessary !

Francis G. Rayer.

This work is Copyright. All rights are reserved. F G Rayer's next of kin: W Rayer and Q Rayer. May not be reprinted, republished, or duplicated elsewhere (including mirroring on the Internet) without consent.